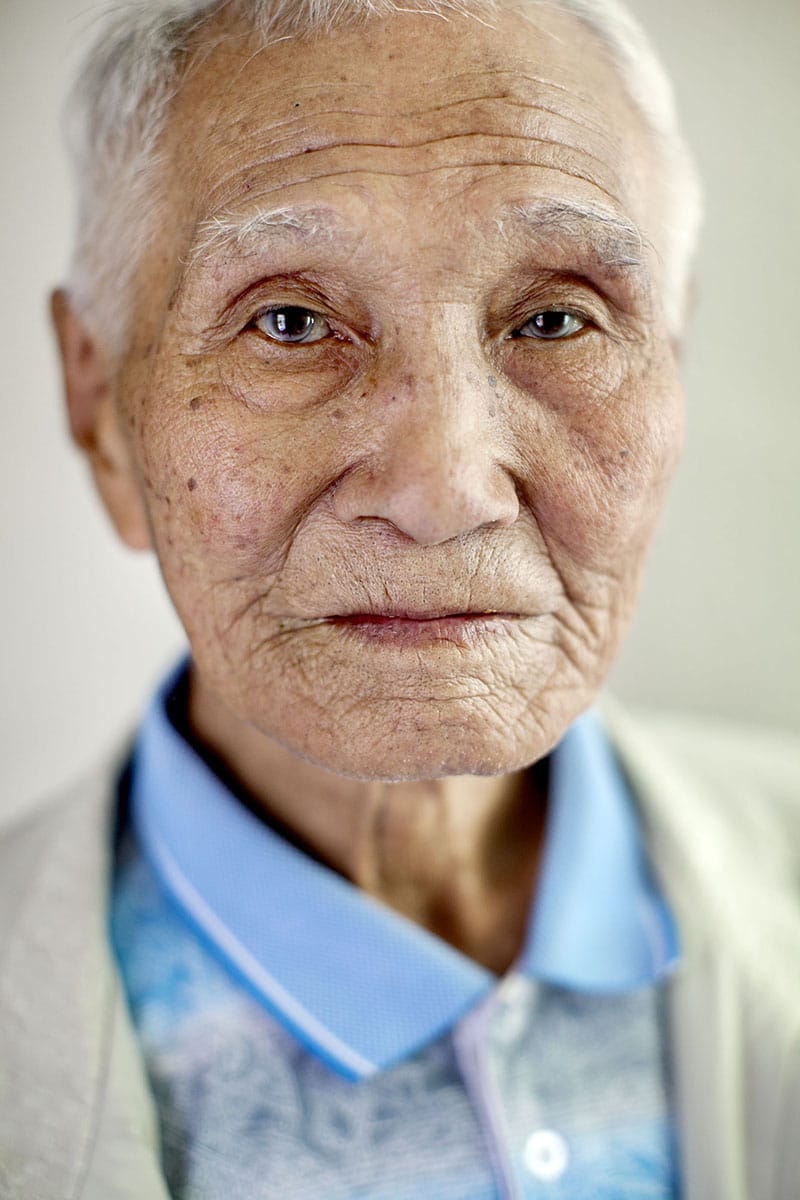

Nam Keung-bong, 87, is searching for his wife and his son, who would now be 68 or 69. He has registered for every inter-Korean family reunion since the first one in 2000 to the most recent one in October 2015. He has never been selected.

“It’s been almost 70 years. Yeah, it was not easy to accept not being chosen. I’ve almost given up. I wasn’t chosen this time.”

Separated family members have to be registered with the South Korean Red Cross to be eligible for reunions. Older people and those wanting to connect with direct relatives—like children, parents, and siblings—are prioritized in the random, computerized selection system.

When asked what he would say if he met his relatives again, Nam said, “Seeing their faces is more important. Why talk?”

It’s been 65 years since the Korean War ended in 1953, which also signifies the last time hundreds of thousands saw their loved ones. For many Koreans, who either have family in the north or moved to the south prior to the war, separation from family is a unfortunate reality. Photographer Laura Elizabeth Pohl, inspired by the story of her own great uncle, who died at 90 without ever knowing the fate of his parents and sisters, explores this tragedy in A Long Separation. By seeking out, photographing, and speaking with Koreans who haven’t seen their family since the war, she’s bringing to light to heart-wrenching plight thousands of Koreans face.

The situation is especially difficult for Korean immigrants to America, who are not eligible for the periodic reunions between separated families—or yisan kajok as they are called in Korean—organized by the North Korean and South Korean Red Cross. Legally, it’s impossible for South Koreans to have contact with North Koreans—and vice versa—meaning many have not seen their spouses, children, siblings, and parents in over 60 years. With many family members entering their 80s and 90s and the prospects of a reunion seem dim, making Pohl’s project all the more poignant. For one country, now separated in two, the divide is more than politics. Beyond sensational headlines, Pohl reminds us of the human toll of war.

A Long Separation is currently on view via a traveling exhibition around libraries in Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, and Massachusetts until May 12, 2018. We had a chance to speak with Pohl about her touching project and what she hopes the public will get out of it. Read on for our exclusive interview.

Kang Neung-hwan, 94, met his son, who lives in North Korea, during the inter-Korean family reunion in Feb. 2014. It was the first time they ever met.

“I can’t lie about the blood (relationship). I can see my blood. Yes, right away I noticed him.”

Mr. Kang is originally from the north and ended up in the south after the Korean War, not knowing his wife in the north was pregnant and that he would never see her again.

“What kind of thinking is this? ‘They are communists and we are a free country.’ Don’t think that way. We are one people from Mt. Baekdu in North Korea to Mt. Halla in Jeju Island, South Korea. We are the same people, so I wish we can unify quickly. I would like to request that the government work a little faster.”

Members of your own family sparked this project. Can you share a bit about your great uncle’s story?

My great uncle moved from the north to the south in his early 20s, just after the Korean War. He wanted to explore life away from his family, especially his dad, whom he found a bit overbearing. But he never imagined he wouldn’t see his sisters or his parents again. I learned of his story when I was in my early 20s, living and working in South Korea far, far away from my family. I spent holidays with my great uncle and he always talked about missing his family and what a terrible son he was. He cried and I cried with him. I couldn’t imagine never seeing my family again. I became very curious to learn more about his story and other people in his situation.

How did you find your participants?

I worked with translators and fixers in South Korea to help me find people to photograph and interview. One of these translators connected me to a woman at the South Korean Red Cross who offered a lot of assistance in finding divided family members. The South Korean Red Cross helps organize family reunions when they happen. There have been 20 reunions since they began in 2000 and at the inter-Korea summit last week, President Moon of South Korea and Kim Jong-un of North Korea agreed to hold family reunions in August. This is great news and I hope it really happens (reunions have been canceled/postponed before).

Kim Soo-Ja, 78, came south with her mother and siblings during the Korean War, leaving behind her aunts and grandparents. Her father died in North Korea during the war when the factory he worked at was bombed.

“I want to visit my father’s tomb. I really, really, really want to go there.”

In Korean culture, it’s important for families to gather at their ancestors’ tombs and pay respects during holidays. Not being able to do so is a tragic situation for many separated family members.

What was the most common thread you found between the people you photographed?

Most people I met with said they wanted political issues set aside and they just wanted to see their loved ones in the north.

North Korea is frequently in the headlines for its politics. What do you think most people forget when it comes to the division of Korea?

I think most people forget or don’t even know in the first place that these divided families exist. South Koreans and North Koreans are not legally allowed to call, meet, write, Facetime, email or otherwise communicate with each other. All these divided family members I met have been involuntarily separated from their family in North Korea for 65 years or more. That’s a humanitarian issue.

Park Ki-Soo, 84, has five siblings living in North Korea. His parents also live there, if they are not already deceased, as he assumes. Park remembers that when he was young he helped his parents, who were farmers, water their crops.

“I helped my parents and I just lived day by day. It was nothing special, actually.”

Park was 17 when a North Korean soldier warned him he would be killed if he didn’t flee. He swam across the freezing Imjin River toward the south in December 1950 with two friends and a brother; his brother died right after the war.

“My siblings and my parents most of all must have missed me,” he said. “They didn’t even have any idea where I went or exactly when, and you know the way parents think of their children – you don’t even have to mention it.”

Park, who is married with five children, wants to see his parents and siblings again. If they’re no longer alive, he wants to know the dates they died so he can perform traditional Korean rituals for the deceased.

Why the choice of a moving exhibition?

I want to reach as many people as possible. By having the exhibit printed on the outside of a vehicle, I’m hoping I get a lot of accidental viewers and visitors. I’ll be driving the truck to public libraries (and one community center) from southeastern Virginia to the Boston area. I have a dream of getting stuck in traffic on the interstate so people see the exhibition there, too.

What do you hope people take away from the work?

I want people to reflect on the long-term unintended consequences of the Korean War and war in general. And I hope people realize that there are real, normal people living in North Korea—people who are loved by their children, parents, brothers, and sisters living in South Korea and the United States.

Choi Chil-seong, 81, was 11 when he came south with two older sisters, after his parents died in the north when he was younger. He left behind relatives whose faces he can’t recall anymore.

Now, after a life filled with marriage, children, and a career in the South Korean military, Choi’s only wish is to see his hometown again.

He visits Imjingak, a town near the border with North Korea, “every New Year’s Day and Thanksgiving day hoping to meet people from my hometown. This country is still divided. My only hope is going back to my hometown, but I cannot do that so I come to this place.”

The South Korean government hosts annual Thanksgiving and Lunar New Year ceremonies at Imjingak for separated family members like Choi. Not being able to visit your hometown is a very sad situation for a Korean. In Korean culture, your hometown is an important part of your social identity, evoking feelings of longing for the warmth, happy memories, and the people and landscape of the area.

Why do you think it’s important to continue to ask our elders about their history?

They all have stories that need to be saved for future generations either because of what they’ve lived through, what they’ve learned about life, or both. In the case of the people I met for this project, they all lived through historical events: the Korean War, the division of the Korean Peninsula, dictatorships in the south, etc. We can learn so much by listening to their first-hand accounts. And so many are eager to talk and really be heard.

What are your hopes for the future of the project?

I want to continue photographing and interviewing divided family members, especially ones who live in the United States.

Laura Elizabeth Pohl: Website | Instagram

My Modern Met granted permission to use photos by Laura Elizabeth Pohl.

Related Articles:

Man Documents Visits to North and South Korea, Reveals Eye-Opening Differences in Daily Life

Soldier’s B&W Photos Capture Rare Glimpse of Seoul Rebuilding After Korean War

Sharing Experiences – I Am Korean American

Stella Im Hultberg Celebrates Her Korean Heritage with New Folklore-Inspired Paintings