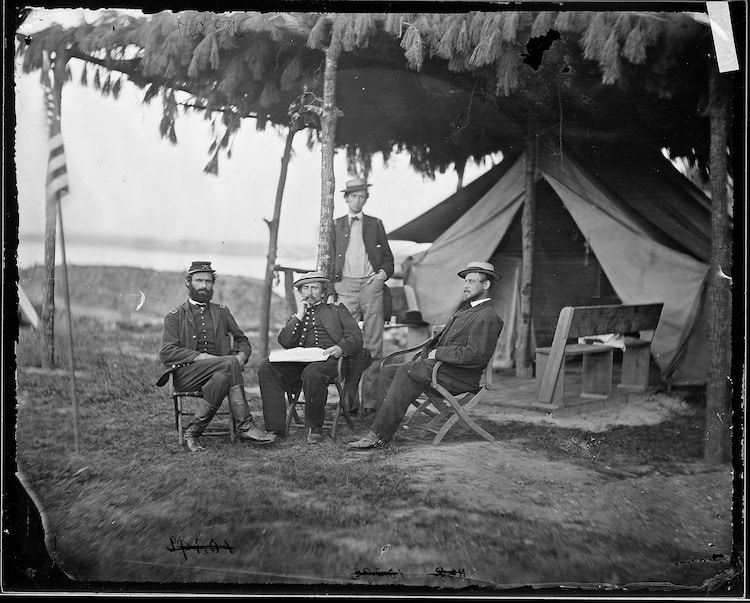

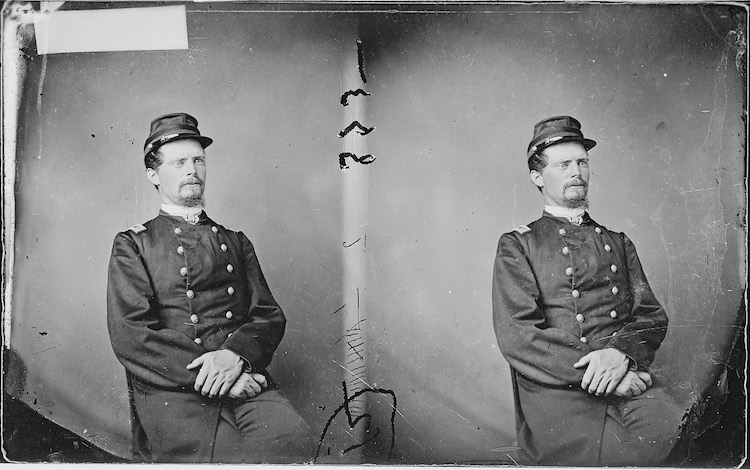

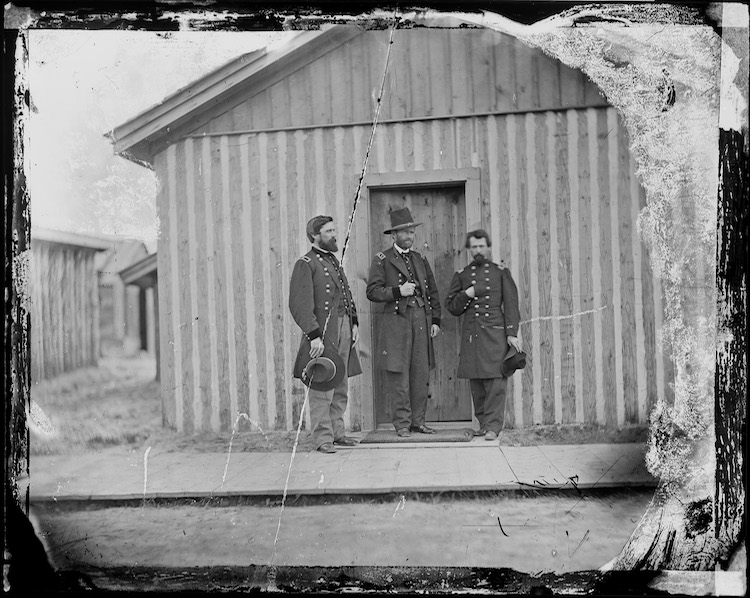

Group of officers, 5th U.S. Cavalry. c. 1863. (Image via U.S. National Archives)

A defining moment in American history, the Civil War is an event that still resonants across the country today. And thanks to one man, we are able to have a first-hand view into what life was like in camp and on the field. Known as the father of photojournalism, we can thank Mathew Brady for exposing the American public to the effects of war for the first time through photography.

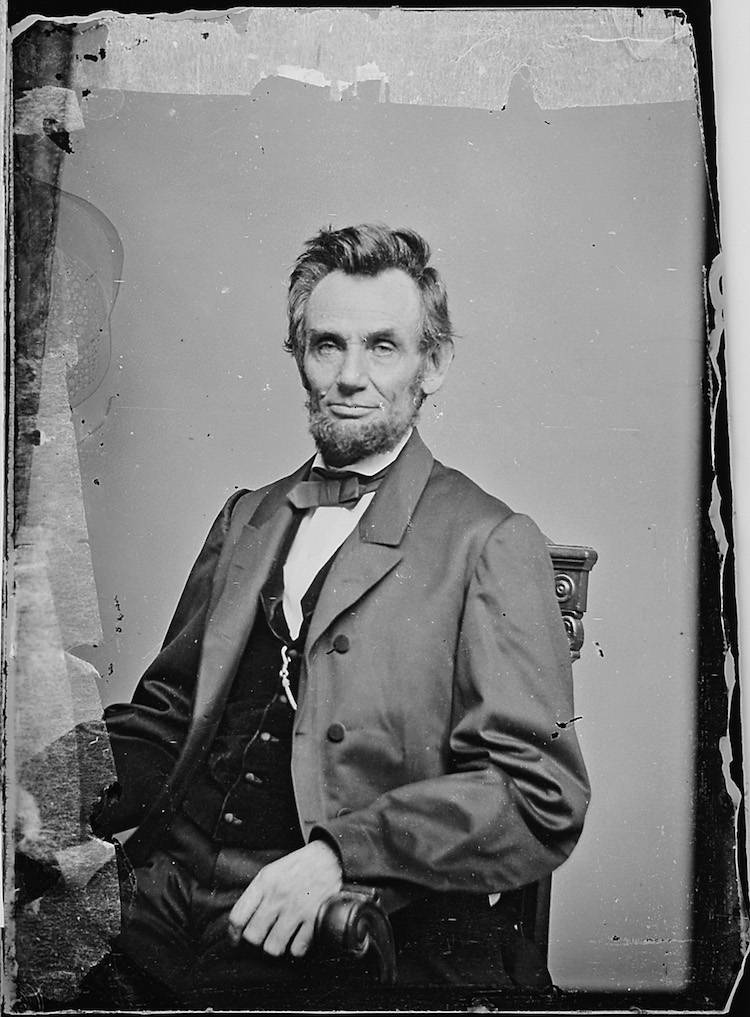

But Brady didn’t only help shape the course of war photography. He is also responsible for shooting portraits of some of the great historical figures of his time. In fact, the photograph of Abraham Lincoln on the $5 bill is by Brady. A man who invested—both personally and monetarily—in his work, Brady was riddled with debt at the end of his life. He spent over $100,000 funding his project to document the American Civil War, producing over 10,000 plates that form the basis of Civil War photography. He eventually sold his work to Congress for just $25,000 but remained deeply in debt at the time of his death in 1895.

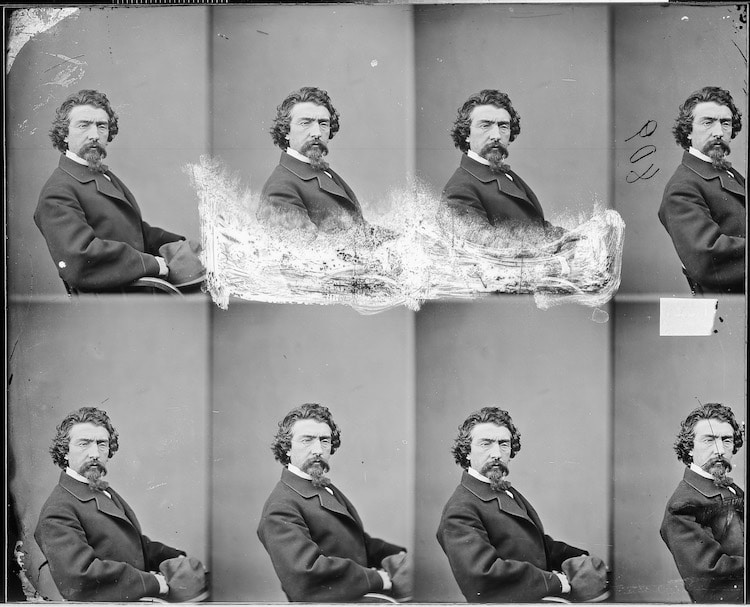

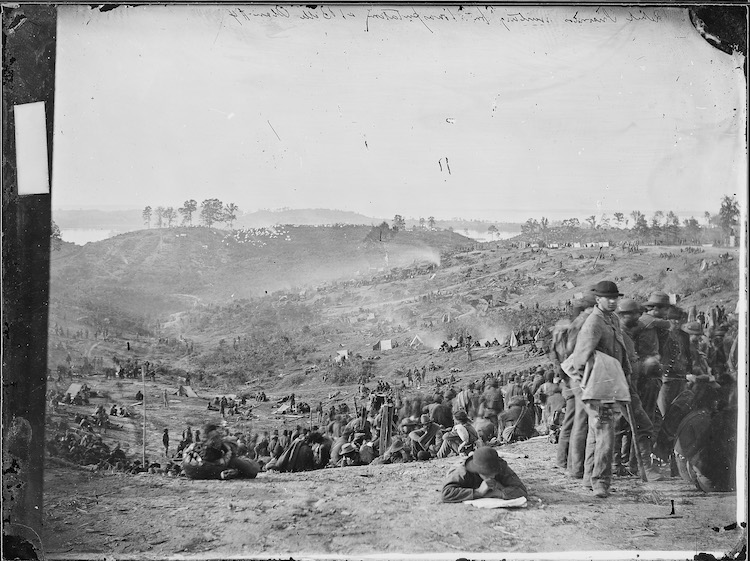

Today we recognize Mathew Brady as a fundamental figure in war photography. Though he may not have shot all the photographs himself—Brady hired a large team of field photographers—there is no doubt that his Civil War photos have become an iconic part of American history. We take a look at his career and contributions both to the history of photography, as well as the preservation of American history.

Self-Portraits. c. 1863. (Image via U.S. National Archives)

Portraits of Illustrious Americans

Abraham Lincoln. c. 1863. (Image via U.S. National Archives)

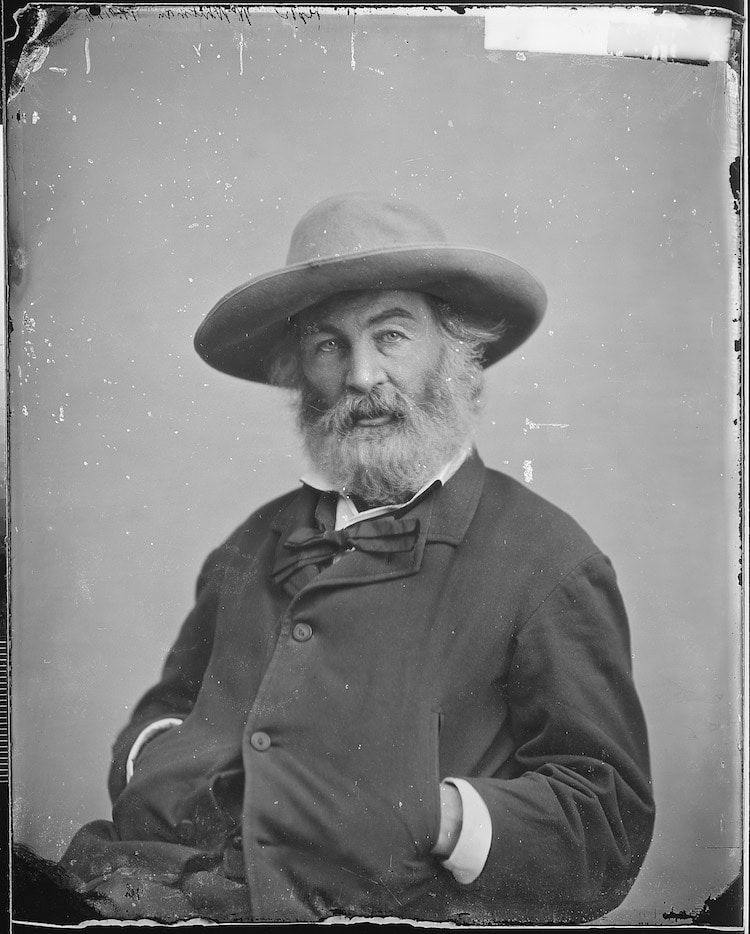

After studying under acclaimed photographer Samuel F. B. Morse and perfecting the daguerreotype process, Brady embarked on his photography career. When Mathew Brady opened his New York photography studio, he mainly focused on daguerreotype portraits of famous Americans. Just one year after opening his practice, he began exhibiting portraits of writers like Edgar Allen Poe and James Fennimore Cooper. He later moved to Washington, D.C. and began photographing prominent politicians. In fact, by the end of his life Brady photographed every president from John Quincy Adams to William McKinley, except for William Henry Harrison, who died after three days in office.

As time went on, Brady’s technique developed, and he moved away from daguerreotype towards the albumen print. These would allow him to produce paper photographs from large glass plates and would be his preferred technique for his Civil War photographs.

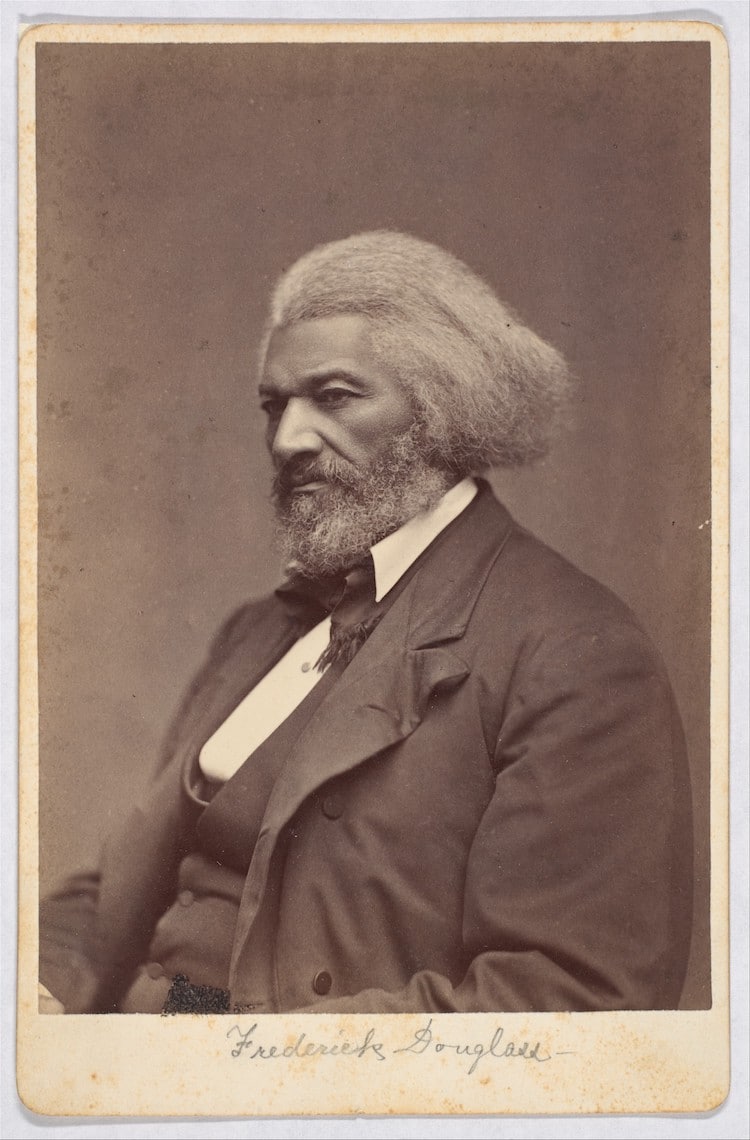

Walt Whitman, Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, Clara Barton, and Daniel Webster were just some of the important figures who sat for portraits with Brady. The best of these images were published in The Gallery of Illustrious Americans. A 1850 publication that sold for $15 at the time—about $450 today. Though not financially successful, the individual images were later reproduced as small visiting cards, with thousands sold throughout the United States and Europe.

Walt Whitman. c. 1863. Image via U.S. National Archives)

Frederick Douglass. ca. 1880. (Image via The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

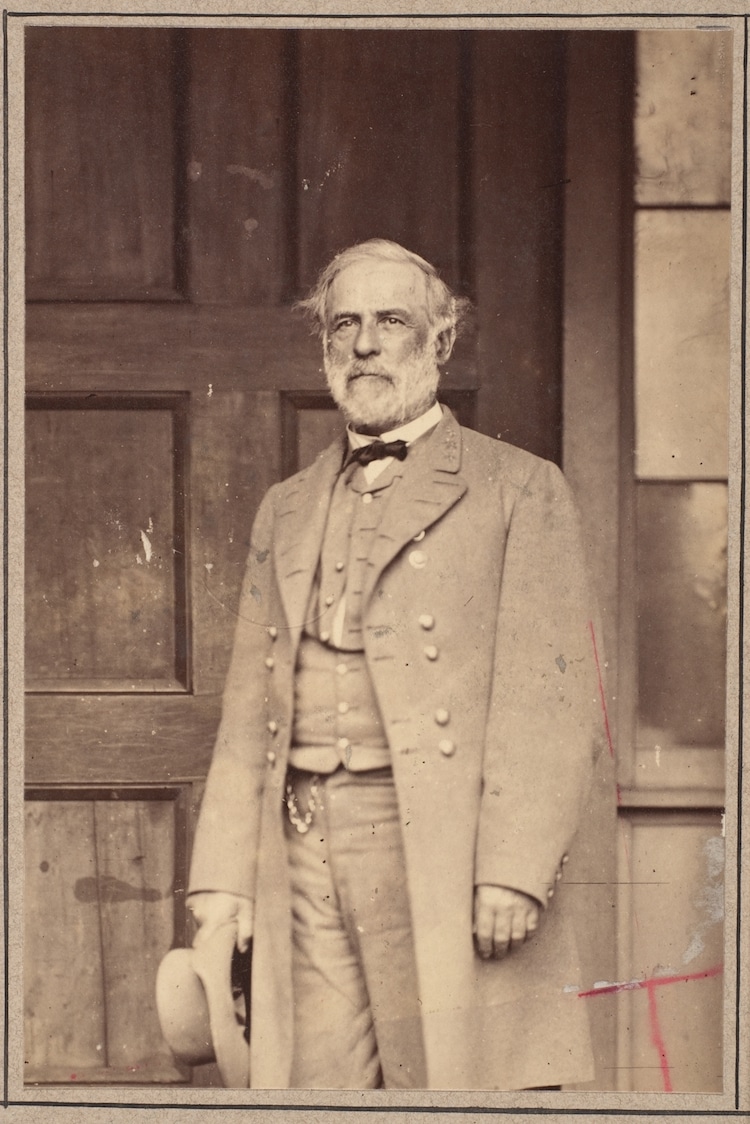

General Robert E. Lee. 1865. (Image via The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Clara Barton. c. 1863. (Image via U.S. National Archives)

American Civil War Photography

Brady’s initial interest in the American Civil War was a continuation of his specialization in portrait photography. He first offered portrait services to soldiers heading off to war, as a sort of remembrance in case they didn’t return. In fact, he even ran an ad in The New York Daily Tribune with the tagline, “You cannot tell how soon it may be too late.”

Office. c. 1863. (Image via U.S. National Archives)

Though he continued taking portraits of important figures throughout the war, photographing senior officers on both the Union and Confederate sides, his focus soon shifted. Taken with the idea of documenting the war first hand, he applied to President Lincoln for permission to travel to battle sites. Lincoln granted his wish in 1861, with the stipulation that he fund the trip himself.

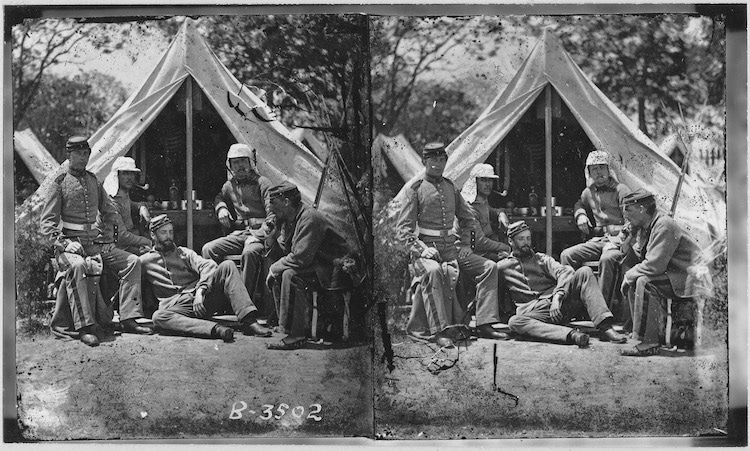

Brady dove headfirst into the war documentation, pulling together a team of field photographers to help him photograph the Civil War. More than 20 men were deployed into the field with traveling darkrooms, though final prints were always published under the Brady name. Though he mainly stayed in Washington, D.C. with assistants, Brady himself came under direct fire at several battle fields, including Bull Run.

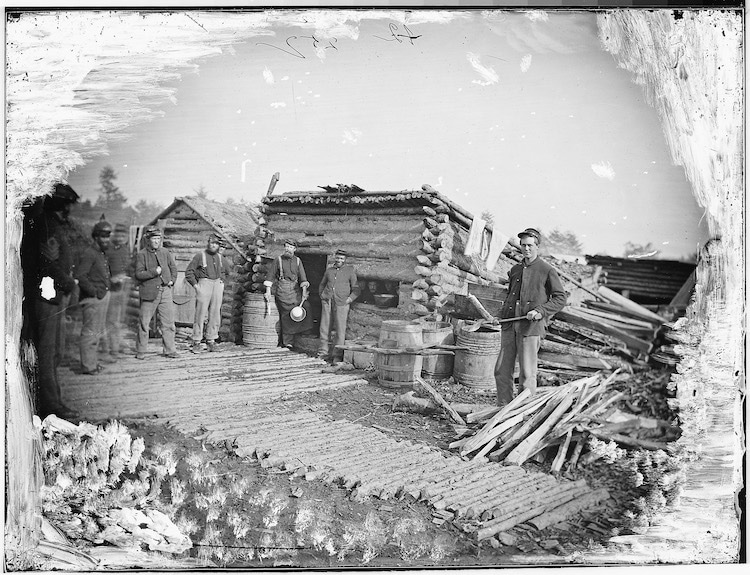

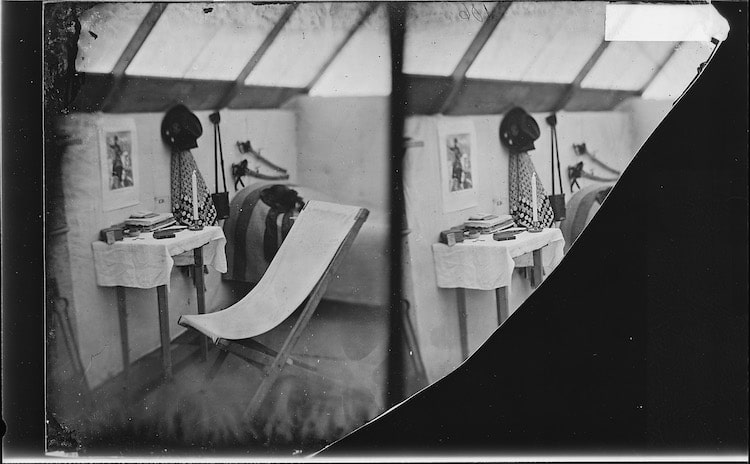

Brady’s Civil War documentation showed life at camp, as well as battle sites. While technical limitations prevented Brady’s team from capturing images in movement, the team’s photography paint a picture of the horrors of war.

Camp scene showing Company kitchen. c. 1863. (Image via U.S. National Archives)

General Ulysses S. Grant and Portion of Staff, General John A. Rawlins. c. 1863. (Image via U.S. National Archives)

Group of 7th Infantry. c. 1863. (Image via U.S. National Archives)

Battery squad on drill. c. 1863. (Image via U.S. National Archives)

Regiment marching down a village street, Gettysburg, PA. c. 1863. (Image via U.S. National Archives)

Inside of tent. (Image via U.S. National Archives)

Confederate prisoners awaiting transportation, Belle Plain, VA. c. 1863. (Image via U.S. National Archives)

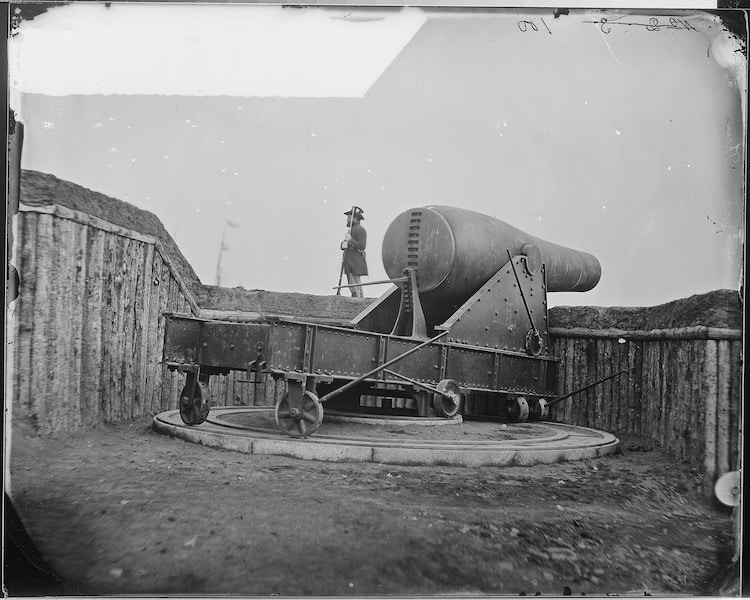

200-lb Gun on Morris Island. Used for Shelling Charleston. c. 1863. (Image via U.S. National Archives)