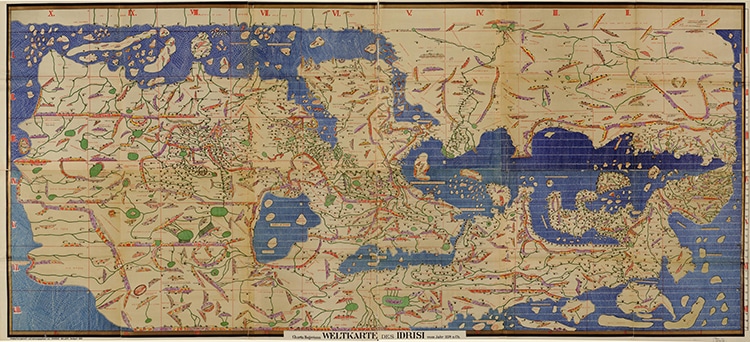

A 1920s facsimile of the world map from the Library of Congress collections. (Photo: Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.)

Cartographers—or map makers—shape how we perceive our world. Most people are not fortunate enough to travel every continent and observe every sea. Even those lucky travelers who manage to accomplish such a feat will find their perspective limited by being Earth-bound, only able to see the horizon in front of them. For centuries before GPS and air travel, before advanced cartographic techniques and easy travel, map makers had to do their best with the restrictions of their time. However, there is one scholar who managed to surpass his predecessors and create an impressively accurate rendition of the world as he knew it—Muhammad al-Idrisi. A 12th-century Islamic scholar and intrepid traveler from Northern Africa, al-Idrisi acted on commission of the King of Sicily to make a magnificent engraved silver map (now lost) and printed works which remained the most accurate reference points for three centuries.

Al-Idrisi was born around the year 1100 in Sabtah, a medieval city which is now the autonomous Spanish city of Ceuta in Northern Africa, next to Morocco. He was educated at Cordoba, a city in Andalusia, in mainland Spain. During his adulthood, he traveled much more widely than many medieval nobles, venturing into Asia, visiting Hungary, York in England, and parts of France. His expertise in the ways of the world inspired the Norman King Roger II of Sicily to commission a work at his court. There, al-Idrisi worked alongside other scholars and the king to compile a map of the world.

After 15 years of work, the final project was completed—a map engraved on a six-feet wide silver disk. Al-Idrisi also compiled a book with text and maps to go along with it, known as Nuzhat al-mushtaq fi ikhtiraq al-afaqI in Arabic, which roughly translates to “the book of pleasant journeys into faraway lands.” The map drew on ancient Greek and Roman knowledge which had been preserved during the Islamic Golden Age, and it specifically rejected the fantastical creatures and places often found on other medieval maps such as the Mappa Mundi.

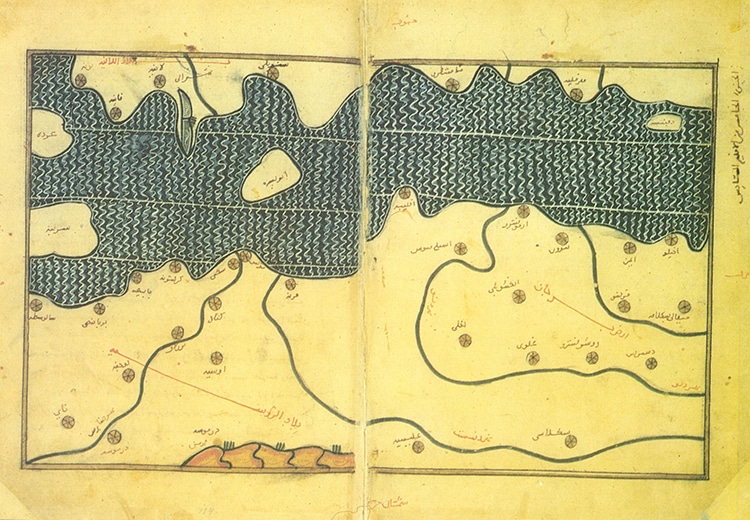

Al-Idrisi’s map, also known as Tabula Rogeriana in Latin, shows the world flipped compared to our modern editions. In this case, south points up which is similar to other Islamic maps of the period. Although the silver disk map and the original paper work in Latin have been lost for centuries, the Arabic version survived long enough to be copied throughout the medieval period. Today, the historic piece survives as ten manuscripts scattered in collections around the world. These maps are partial, depicting the Balkans or Sicily for example. It wasn’t until the 1920s that a German historian called Konrad Miller reconstructed the pieces to produce the full map as it may have appeared on the silver disk.

While the geographic formations are not entirely accurate—like most ancient maps—al-Idrisi’s work remained authoritative throughout the medieval period. It does not include southern Africa, nor the Americas, but it was a much wider, more accurate view of Europe and Asia than most scholars would have seen at the time. It was also a big step in the history of scientific mapmaking, demonstrating the skill of Golden Age Islamic scholars.

The medieval Islamic cartographer and scholar Muhammad al-Idrisi created a world map in the 12th century which remained the most accurate for three centuries.

A circular map found in later editions of al-Idrisi’s work, this from ‘Alî ibn Hasan al-Hûfî al-Qâsimî’s 1456 copy. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

The map was originally engraved on a silver disk and a paper compendium accompanied it.

The Balkans as depicted by al-Idrisi. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

h/t: [Open Culture, Library of Congress]

Related Articles:

Insightful Map Reveals Different Etiquette Practices Around the World

Antique Map Acquired at Estate Sale Turns Out to Be an Extremely Rare 14th-Century Portolan Chart

This 19th-Century Atlas Has Raised Maps for Blind Readers

19th-Century Map Shows That Beaver Dams Can Last Over a Century