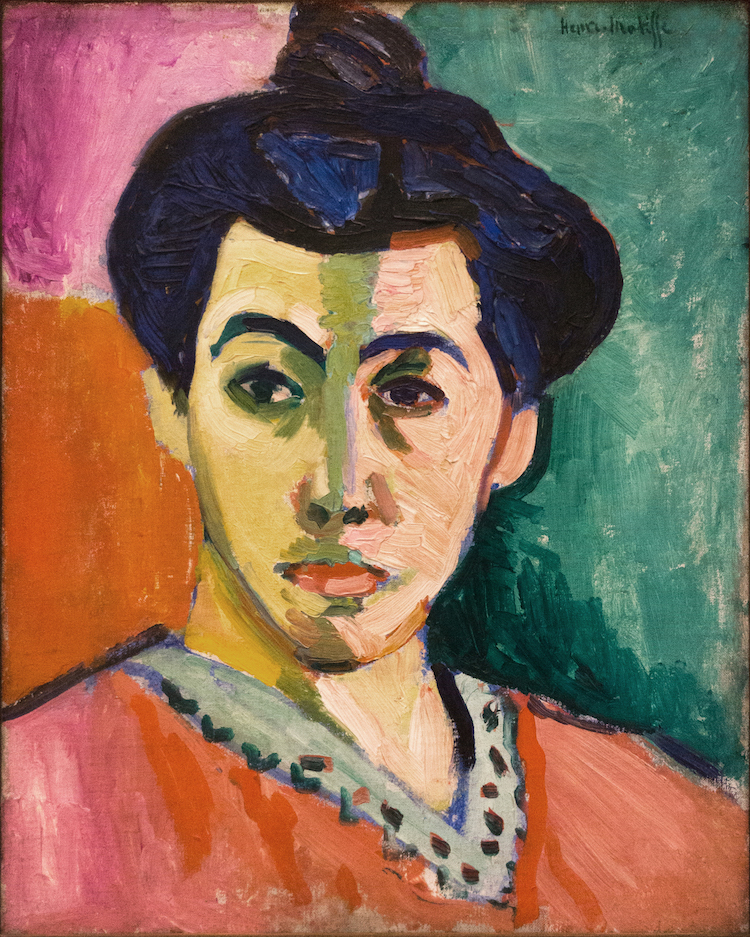

Henri Matisse, “Portrait of Madame Matisse. (The Green Line),” 1905 (Photo: Statens Museum for Kunst via Wikimedia Commons Public Domain) This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

At the start of the 20th century, the modern art movement was taking shape around the world. In Austria, Gustav Klimt was crafting his glimmering gold paintings. In Tahiti, ex-patriate Paul Gauguin was keeping Post-Impressionism alive. And in France, a “wild” group of artists founded Fauvism, a genre defined by an expressive approach to painting.

Unlike most other major art movements, Fauvism lasted for only a few years. While the Fauve practice was short-lived, its impact is anything but. Here, we take a look at the movement in order to understand the longevity of its legacy.

What is Fauvism?

Fauvism is a movement co-founded by French artists Henri Matisse and André Derain. The style of les Fauves, or “the wild beasts,” is characterized by a saturated color palette, thick brushstrokes, and simplified—often nearly abstracted—forms. The movement flourished in Paris and other parts of France from 1905 until 1910.

History

In the 1890s, Symbolist artist Gustave Moreau taught Matisse and other French painters like Georges Rouault and Albert Marquet at Paris’ École des Beaux-Arts, or the “School of Fine Arts.” His deep appreciation for pure color and unconventional approach to art inspired Matisse and his peers to experiment with their own palettes and painting techniques in the years leading up to the turn-of-the-century.

Henri Matisse, “The Little Gate of the Old Mill,” 1898 (Photo: Wiki Art Public Domain)

Moreau’s students were not the only future Fauve painters exploring new frontiers of art at this time. Others, including André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, were also pushing painting’s boundaries. Specifically, they looked to the flat compositions of Paul Cézanne and the “exotic” colors of Paul Gauguin for inspiration.

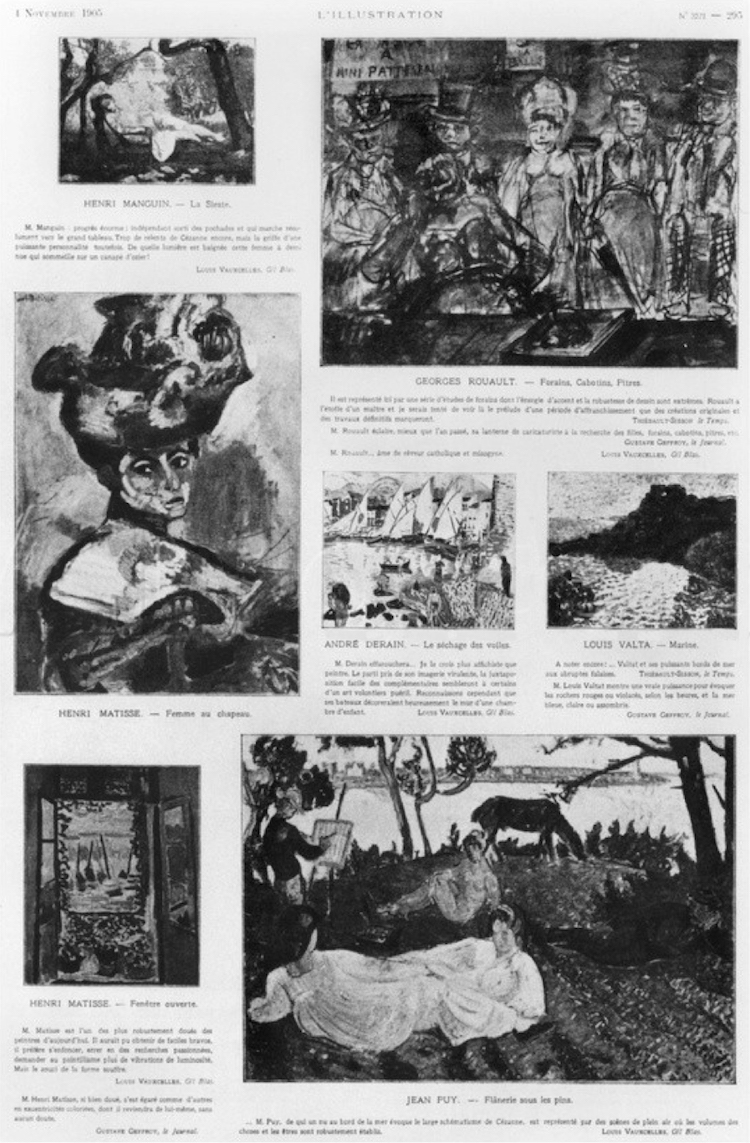

In 1905, these avant-garde advancements in painting were pushed to the forefront following the Salon d’Automne (“Autumn Salon”), an independent art exhibition in Paris. Here, Matisse, Derain, De Vlaminck, and other artists exhibited their distinctive art, which was met with disdain by art critics—namely, Louis Vauxcelles, who famously described the artists as “les Fauves.”

Press clipping, Le Salon d’Automne, Les Fauve, journal L’Illustration, November 4, 1905 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Though intended to demean the movement, this term was embraced by the artists, who adopted it as their official title until the end of the movement in 1910.

Defining Characteristics

Vivid Colors

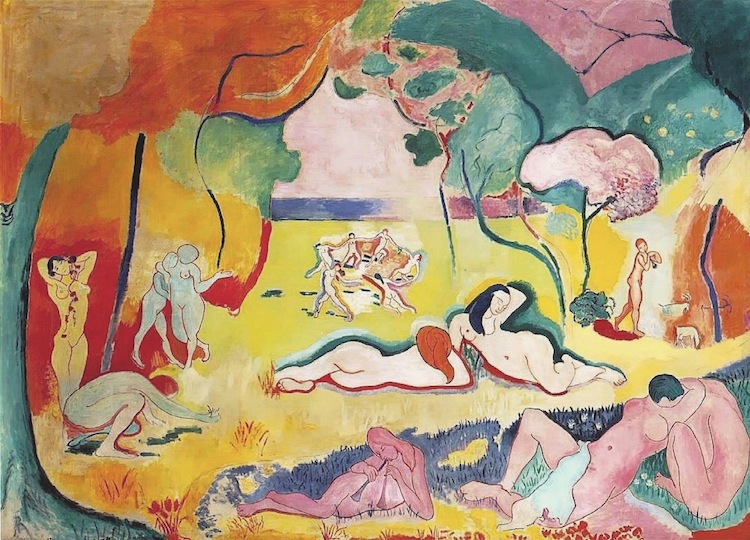

The characteristic most prominently associated with Fauvism is a bright and bold use of color. Matisse’s large-scale painting, Le bonheur de vivre, illustrates this interest. Though the scene is based in a natural setting, Matisse forewent neutral tones for a kaleidoscopic color scheme. In addition to orange trees, blue grass, and a pale pink sky, he also rendered the figures in a rainbow of hues.

Henri Matisse, “Le bonheur de vivre,” ca. 1905-1906(Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

To Matisse, the relationship between the colors on a canvas is intrinsic to the color selection process. “There is an impelling proportion of tones that can induce me to change the shape of a figure or to transform my composition,” he wrote in Notes of a Painter. “Until I have achieved this proportion in all the parts of the composition I strive towards it and keep on working. Then a moment comes when every part has found its definite relationship, and from then on it would be impossible for me to add a stroke to my picture without having to paint it all over again.”

“Wild” Brushwork

The Fauves did not strive for realism in their brushwork. Introduced by the Impressionists and adapted by Post-Impressionist artists like Vincent van Gogh, thick, painterly brushstrokes dominated their paintings. What set the Fauves’ approach apart, however, is the preparation of the paint itself.

Maurice de Vlaminck, “The Seine at Chatou,” 1906 (Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art via Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Rather than apply their oils from a palette, Fauves would often squeeze tubes of paint directly onto the canvas. Similarly, instead of mixing pigments, they would suggest new colors through the use of small, adjacent strokes.

Simplified Forms

Taking a cue from Paul Cézanne, the Fauves experimented with abstraction. Rather than render forms as they appear in real life, they preferred painting them as simplified shapes. Similarly, like the Post-Impressionist pioneer, they played with perspective and skewed the picture plane, resulting in flat compositions that emphasize color and brushwork over spatial depth.

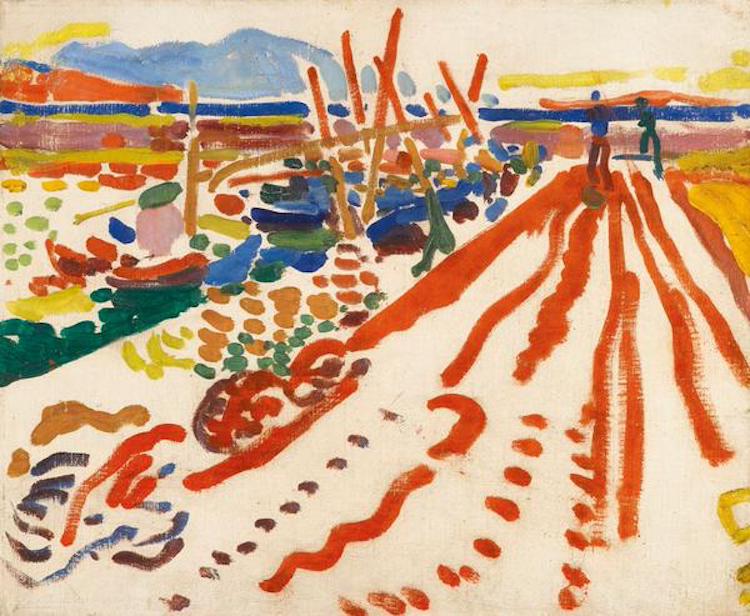

André Derain, “La jetée à L’Estaque,” 1906 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

“When one enters the gallery devoted to their work, at the sight of those landscapes, these figure studies, these simple designs, all of them violent in colour, one prepares to examine their intentions, to learn their theories; and one feels completely in the realm of abstraction,” French painter Maurice Denis wrote in an exhibition review. “Here one finds, above all in the work of Matisse . . . the act of pure painting.”

After Fauvism

Fauvism acted as a transitional period for many of the artists associated with it. Following its conclusion in 1910, these figures used their Fauve experience to embark on new projects and enter new periods.

Cut-Outs

In the early 20th century, a rivalry formed between Matisse and Pablo Picasso. As each figure longed to be at the forefront of modernism, they strived to stand out with their avant-garde art. Famous for his seemingly ever-changing style, Picasso was constantly producing new work. In order to keep up, Matisse had to evolve, too.

However, traces of Fauvism are seen throughout his oeuvre—notably, in his Cut-Outs. Produced in the late 1940s, these painted paper creations reference the Technicolor palette of Fauvism. Similarly, the abstract shapes and silhouettes of these snipped sheets of paper call to mind the simplicity of Fauve forms.

“From Bonheur de Vivre—I was thirty-five then—to this cut-out—I am eighty-two—I have not changed,” Matisse said, “not in the way my friends mean who want to compliment me, no matter what, on my good health, but because all this time I have looked for the same things, which I have perhaps realized by different means.”

Homage to Cézanne

Unlike Matisse, who employed a bright color palette throughout his entire career, some of his fellow Fauves opted to eventually explore earthy hues. This interest in a more neutral palette is particularly pronounced in the post-Fauvism work of André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, who found inspiration in the landscapes of Cézanne.

Cézanne’s tonal treatment is not the only characteristic adopted by these artists after 1910. Many of them replaced Fauvism’s fluid forms with Cézanne’s geometric approach. This is particularly evident in Cubism.

André Derain, “Ancien quartier de Cagnes,” 1910

Cubism

Along with Pablo Picasso, French artist Georges Braque is credited with co-founding Cubism, a style characterized by the fragmentation of subject matter. While, today, Braque is predominantly associated with this movement, he also worked in the Fauve style from 1905 until 1907, when Cubism emerged.

Braque’s experience as a Fauve undoubtedly influenced his subsequent work as a Cubist. Like his Fauve paintings—namely, his landscapes—his Cubist works are broken down into flat planes of color. While his former palette is much more vibrant than that of the latter, both convey an interest in inventing this new type of perspective.

Georges Braque, “The Viaduct at L’Estaque,” 1907 (Photo: Sharon Mollerus via Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

“I felt dissatisfied with traditional perspective,” Braque said in an interview. “Merely a mechanical process, this perspective never conveys things in full. It starts from one viewpoint and never gets away from it. But the viewpoint is quite unimportant. It is though someone were to draw profiles all his life, leading people to think that a man has only one eye . . . When one got to thinking like that, everything changed, you cannot imagine how much!”

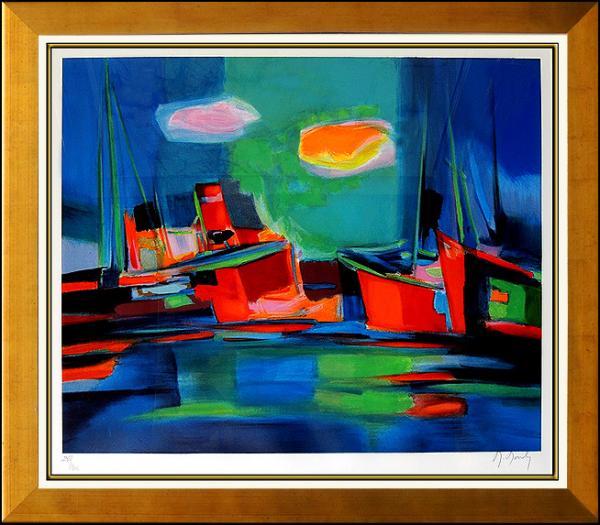

Contemporary Art

Today, many artists put a new twist on this century-old movement. From Todd James‘ fluorescent portraits to Marcel Mouly‘s multicolored landscapes, these works convey the Fauves’ wild brushwork and vivid color through a contemporary lens. By reimagining and reinterpreting this style, contemporary artists illustrate its versatility and prove its place as a major modern art movement.

Related Articles:

Bauhaus: How the Avant-Garde Movement Transformed Modern Art

6 Contemporary Artists Who Are Keeping Pop Art Alive Today

7 Colorful Masterpieces That Define the Pop Art Movement

19 Inspirational Quotes From True Artists to Help You Overcome a Creative Rut