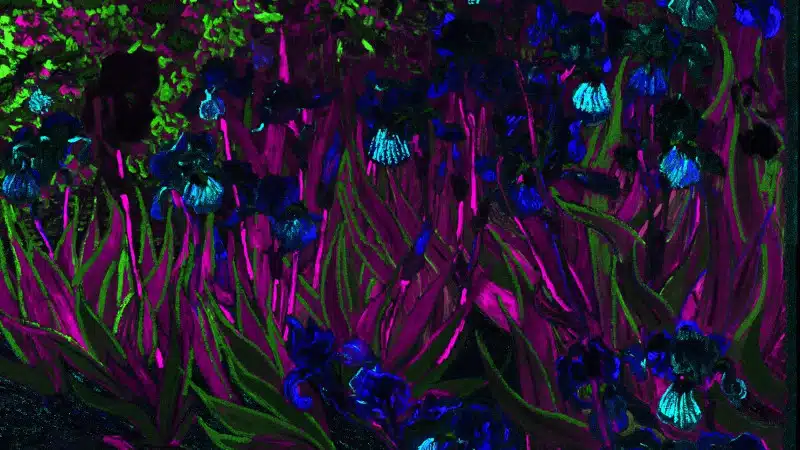

“Irises,” 1889, Vincent van Gogh. Oil on canvas Photo: Vincent Van Gogh via Wikimedia Commons (Public domain)

The painting Irises is one of Vincent van Gogh’s most well-known works of art. The deceptively simple piece has captivated academics and the general public for centuries, particularly for the way the blue flowers evoke a calming, reflective feeling. However, it turns out that these flowers weren’t always blue. New research at the Getty Museum has revealed that these world-famous blooms were actually purple when they were conceived and painted by the Dutch artist.

The Getty Museum has been home to Irises since it acquired the painting in 1990. As one of the crown jewels of the collection, the artwork is always on view—something that prevented the museum authorities from taking a better look at it. “The Museum’s closure during the COVID pandemic provided an opportunity to bring the painting into the studio for extensive research and analysis,” says Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum.

The findings from these studies are at the heart of a new exhibition titled Ultra-Violet: New Light on Van Gogh’s Irises. Looking at the painting through modern conservation science, the exhibition explores the way Van Gogh’s understanding of light and color informed his paintings, as well as the scientific processes used by contemporary researchers to unravel the artist’s techniques and preferred materials.

The biggest discovery is that the light has irrevocably changed some of the colors in Irises. Particularly, the flowers were originally purple, something hinted at in a letter the artist wrote to his brother Theo, where he wrote that he was working on a painting of “violet irises.” Another key finding is that the painting was indeed created en plein air, as scientists spotted a pollen cone that became embedded in the wet paint.

“Van Gogh created violet paint by mixing blue and red paints,” writes the museum. “Using non-invasive analytical techniques like X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, Getty researchers discovered markers for the highly light-sensitive red pigment called geranium lake. This pigment has since faded dramatically due to light exposure early in the painting’s history. Van Gogh, along with other 19th-century European artists, understood that some pigments they used, including geranium lake, were susceptible to alteration yet chose to employ them regardless.”

To show the public how the painting might have looked when it was first painted, Getty researchers prepared a digital reconstruction of the painting that will be part of the exhibition, alongside some other pieces surrounding the creation of Irises, such as replica of a red lacquered box with balls of yarn he used to explore relationships between colors, and the original letter Van Gogh wrote to Theo soon after he began painting Irises. Both items are a loan from the Van Gogh Museum in the Netherlands.

Ultimately, the exhibition sends a broader message beyond a single painting—one about how technology and art history can come together to tell a more complete story about centuries-old, world-famous works of art. “Art conservation is a prime example of how science intersects with art, bringing together art history with scientific research,” states Potts. “This exhibition showcases the revelatory results of those studies.”

New research at the Getty Museum has revealed that the blooms in Van Gogh’s world-famous Irises were actually purple when they were conceived and painted.

XRF of “Irises” (detail), 1889, Vincent van Gogh. Oil on canvas. Photo: Getty Museum

Source: Getty Investigates Color Change of Van Gogh’s Irises

Related Articles:

Van Gogh’s “The Starry Night” Hides Atmospheric Physics

Stolen Van Gogh Painting Recovered in an IKEA Bag Will Go on Display

1,500 Van Gogh Artworks Have Been Digitized and Put Online

Vincent van Gogh’s Life Illustrated in His Imaginative Style of Swirling Colors