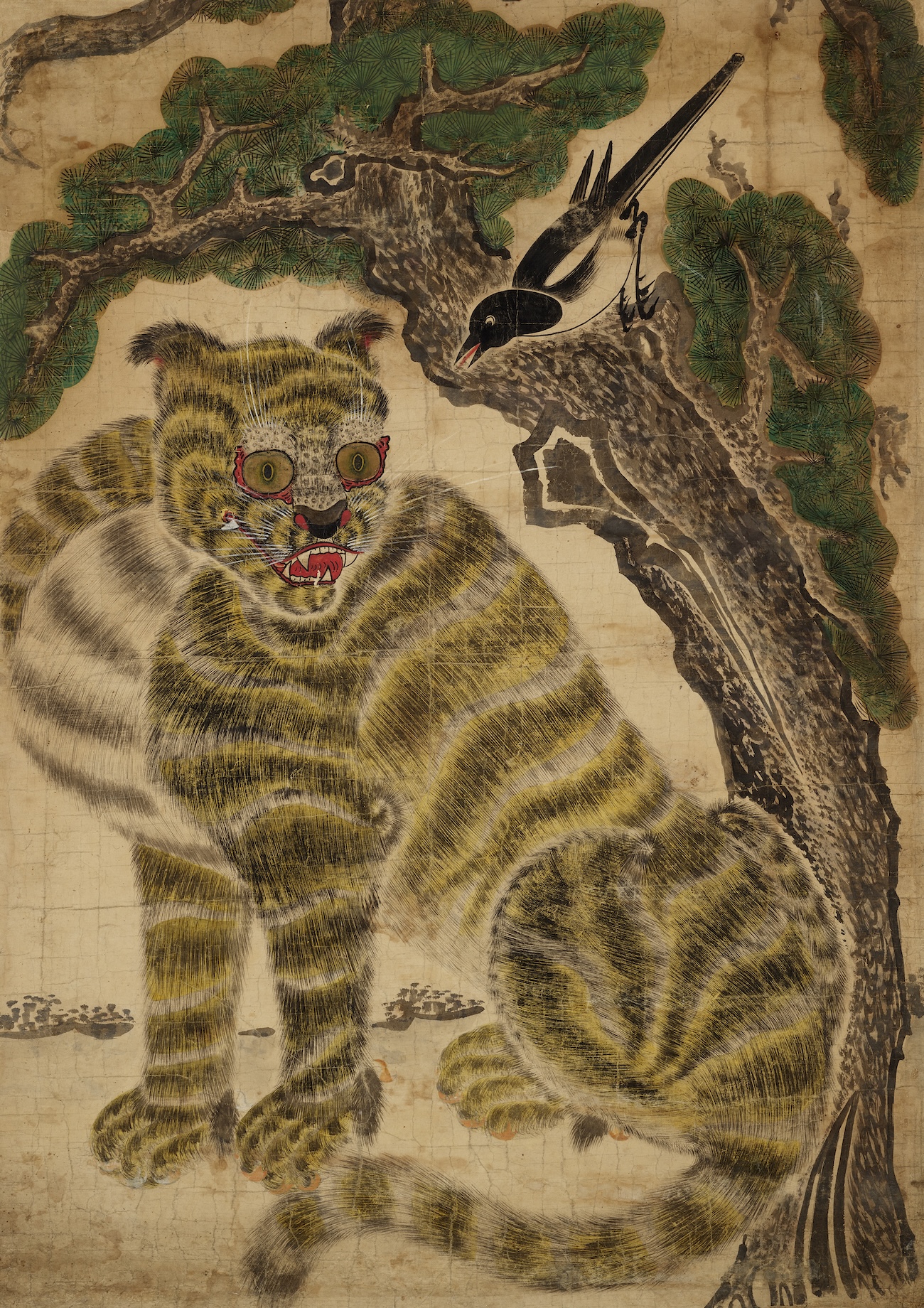

“Tiger and Magpie,” by Unidentified artist. Joseon Dynasty, late 19th century. Colors on paper. 116.5 × 83.0 cm. Private collection.

In this classic example of a tiger and magpie painting, a magpie in a pine tree seems to be speaking to a huge tiger, which is listening intently. This scene might be inspired by folk tales in which magpies serve as messengers for the mountain spirit and deliver divine messages to tigers in places beyond the spirit’s reach. The tiger in the painting is depicted relatively realistically, even down to the detail of its fur. However, its comical facial expression and disproportionate size compared to the pine tree are distinguishing traits of folk painting.

Folk paintings are one way in which a culture portrays its attitudes and beliefs. Often created by artists who lack formal training, these pieces are an important part of a society’s culture, and we can look to them as a guide to the visual language of the time in which they were produced. In Korean culture, the magpie and tiger are a pair common in traditional folk art paintings. The two beloved animals have been featured in artwork for centuries. Their union is called hojakdo, in which “ho” refers to tiger, and “jak” refers to magpie. Now, an aptly titled exhibition, Tigers and Magpies, is on view at the Leeum Museum of Art in Seoul, showcasing the various forms these paintings have historically taken.

Why are tigers and magpies together? There are theories on why, and one guess begins with tigers. In Korean folklore, tigers are believed to protect against misfortune. They have long been a common motif in traditional art, and from there, the creature has been paired with other animals to layer meaning in the artwork.

Hojak paintings are believed to have developed from the pairings. Chulsanho is one example. It translates to “tiger descending the mountain,” and it refers to paintings where the big cat is seen asserting its authority over animals that have been impersonating it—those lower in the food chain, like foxes and wolves. Another is known as gyeongjo, which means “surprised bird,” and are paintings in which a feathered creature is surprised and delighted by the birth of a tiger cub. Yuho, one more example, means “nursing tiger” and depicts a mother tiger raising cubs. Here, it symbolizes an extraordinary person born with a talent.

Tigers and Magpies displays an important work within the hojak tradition. The exhibition has unveiled, for the first time, a 1592 painting on silk that features a magpie resting on a branch above a tiger and its cubs. It’s considered a formal painting, in contrast to the other works from the 19th century. They are relatively newer pieces that utilize humor and layer meaning, while still being interpreted as scenes from traditional folklore. One way this is done is through social satire; the tiger is a corrupt official, and the magpie symbolizes common folks who “chirp” or outright ignore the tiger.

Tigers and Magpies is currently on view until November 30, 2025, at Leeum Museum of Art.

In traditional Korean culture, tigers and magpies are a common theme in folk art paintings. Their pairing is called “hojakdo.”

“Tigers and Magpies,” by Unidentified artist. Joseon Dynasty, 1592. Ink on silk. 160.5 × 95.8 cm.

This work is considered to be the prototype of tiger and magpie paintings, which later became one of the representative themes in folk art of the late Joseon period. The tiger and magpie motif is thought to have originated in China’s Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368). In this painting, the artist transposed the basic elements of the motif into a uniquely Korean iconography, with a magpie perched on the branch of a pine tree above a tiger and her cubs. The rocks and bamboo are rendered in the style of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century paintings. An inscription on the upper right states that this painting was made in the “year of imjin,” which corresponds to 1592. As the oldest extant Korean painting of a tiger and magpie, this work is a priceless masterpiece with tremendous importance for art history.

An aptly titled exhibition, Tigers and Magpies, is on view at the Leeum Museum of Art in Seoul, showcasing the various forms these paintings have historically taken.

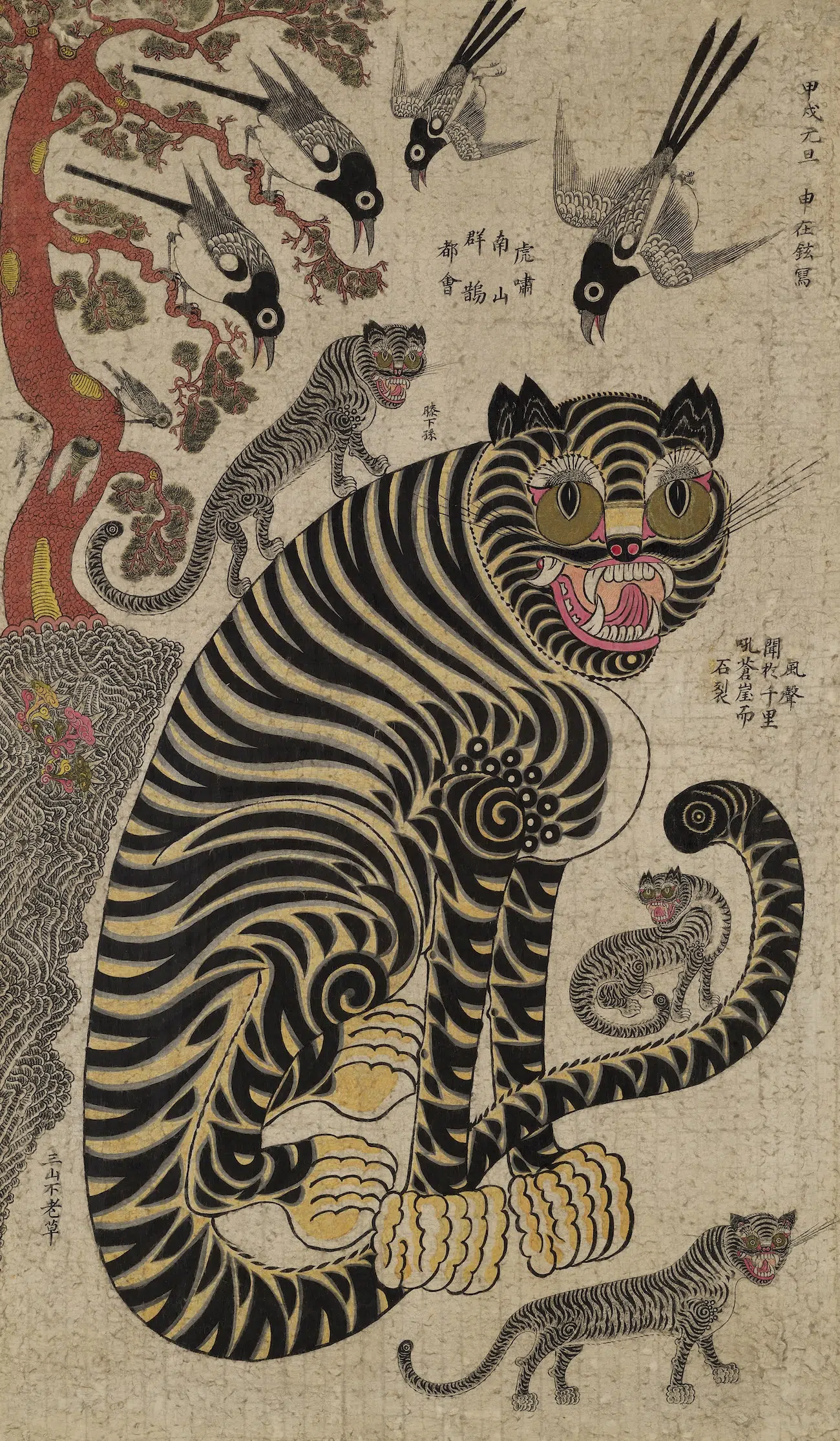

“Tigers and Magpies,” by Sin Jae-hyeon. Joseon, estimated 1874. Colors on paper. 116.5 × 83.0 cm. Private collection.

Scenes of a mother tiger and her cubs are a classic theme in Korean traditional art, known as “yuho” (乳虎, “Nursing Tiger”) paintings. This painting is particularly interesting for its inclusion of magpies, thus merging the yuho and hojak motifs. Various inscriptions are written on the painting, including one that reads, “Sin Jae-hyeon painted this in the year of gapsul,” thus revealing the artist and estimated date. Other inscriptions say, “When the tiger roars, the magpies gather” and “Its roar can be heard for a thousand miles, shaking the cliffs,” indicating that the painting was likely intended to convey moral lessons to children. This work has special significance as an extremely rare example of a tiger and magpie painting with a known artist and date.

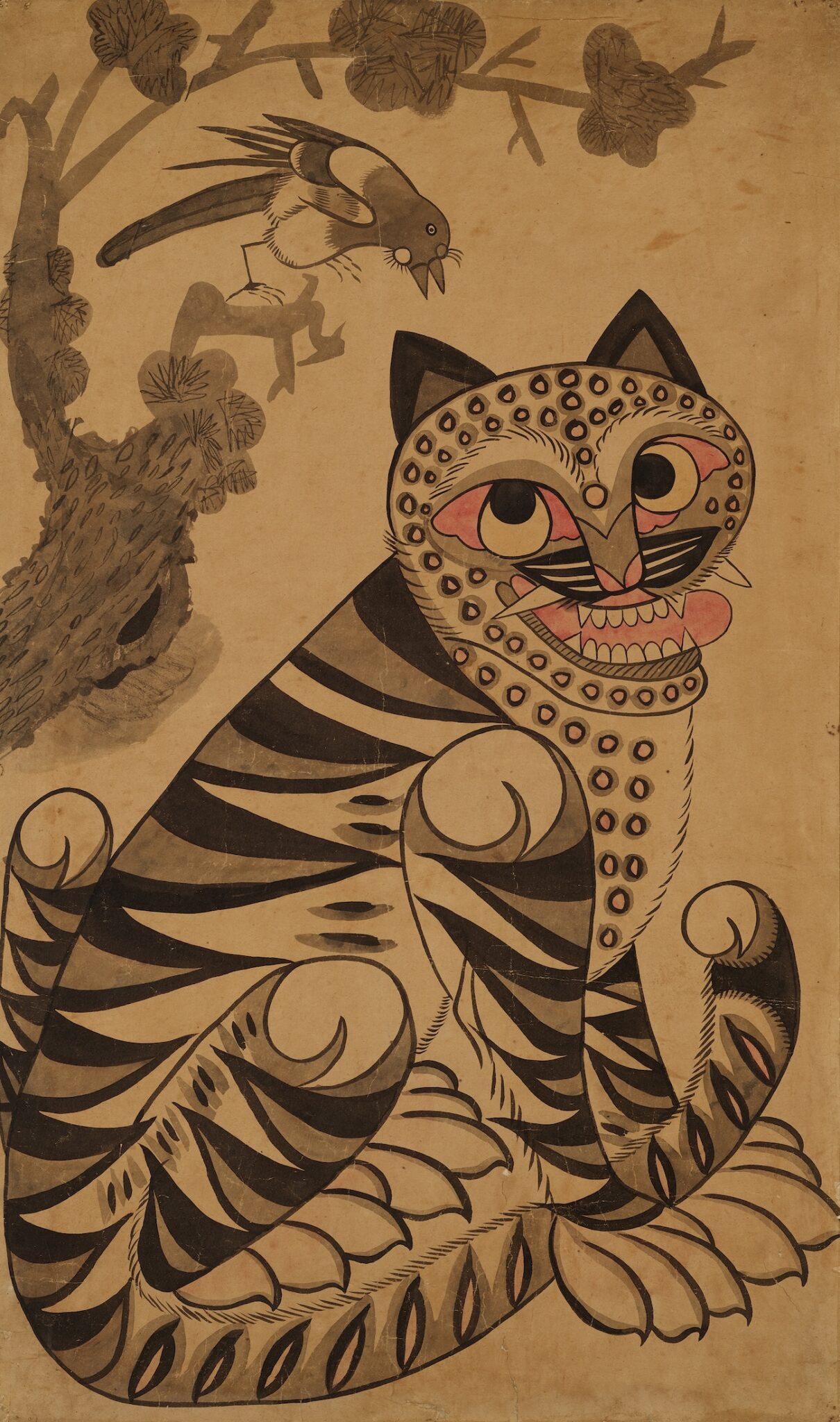

“Tiger and Magpie,” by Unidentified artist. Joseon, 19th century. Ink and light colors on paper. 91.7 × 54.8 cm. Private collection.

This is one of the most famous of all extant Korean paintings of tigers and magpies. It is sometimes called the “Picasso Tiger,” since the abstract expression is reminiscent of the style of Pablo Picasso. The tiger listens attentively to the magpie, which is likely conveying a divine message from the mountain spirit. The schematic overall style and comical facial expression of the tiger are typical characteristics of folk painting. Interestingly, the tiger’s face and chest are covered with spots, like a leopard, while the rest of its body has the distinctive stripes of a tiger, as if it is a hybrid of the two. This can likely be attributed to the fact that, at the time, leopards and tigers were generally regarded as the same creature. As one of the representative folk paintings of tigers and magpies, this work was the inspiration for “Hodori,” the mascot of the 1988 Seoul Summer Olympics.

Tigers and Magpies is on view until November 30, 2025.

“Tiger and Magpies,” by Unidentified artist. Joseon, 19th century. Colors on paper. 86.7 × 53.4 cm. Private collection

This painting shows a tiger snarling at a pair of magpies in a pine tree. Although the tiger is baring its fangs and glaring with its eyes wide open, it still appears more friendly than fearsome, while the magpies seem unperturbed by the tiger’s threat. One of the possible interpretations of tiger and magpie paintings is that the tiger may represent corrupt government officials, while the magpie represents the common people who oppose them. Based on the humorous juxtaposition of the blustering tiger and indifferent magpies, that interpretation seems especially applicable for this painting. Despite being a folk painting, this work shows exceptional skill and artistry, particularly in its meticulous brushwork and detailed depiction.

“Curtain of Tiger Pelts,” by Unidentified artist

Joseon, 19th century. Colors on paper. 128.0 × 355.0 cm. Private collection

This painting depicts a long curtain of tiger pelts, which is parted in the middle to reveal the interior of a sarangbang (the male quarters of a traditional Korean home, which served as a study). Paintings of tiger or leopard skins were relatively common in Korean folk painting, reflecting the contemporaneous perception that leopards and tigers were the same creature, and that their pelts had the power to ward off evil spirits and misfortune. However, this painting seems to have been produced for different purposes related to literati culture, based on the presence of an unknown poem by the scholar Jeong Yak-yong within the study. The poem refers to a passage in the Book of Changes (I Ching), which likens one’s transformation into a virtuous person or “gentleman” in the Confucian sense to a leopard’s renewal of its brilliant coat. Notably, tigers were also commonly used to symbolize a virtuous person in the tradition of formal paintings. Hence, this is a highly intriguing and important work for studying the relationship between formal painting and folk painting.

Get a peek into the Leeum Museum of Art, where the exhibition is located:

View this post on Instagram