Langen Foundation, 2004. (Photo: Perlblau at German Wikipedia. (Transferred from de.wikipedia to Commons.) [CC BY-SA 2.0 de], via Wikimedia Commons)

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

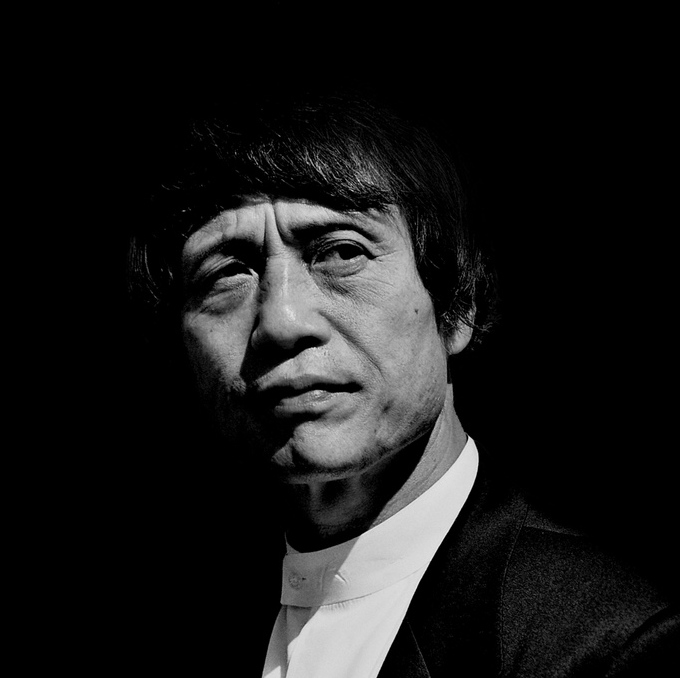

Acclaimed Japanese architect Tadao Ando has cultivated a visually rich, modern aesthetic that is truly his own. By balancing aspects of modernism with Japanese principals of design, Ando has been able to carve an impressive name for himself in the architecture world. His accomplishments include winning the 1995 Pritzker Prize.

His career is all the more impressive when one considers that he’s largely self-taught. Born in 1941 in Osaka, Ando worked as a professional boxer and truck driver before apprenticing as a carpenter and turning to design. After continually attempting to have his carpentry clients accept his designs, only to be turned down, he decided to teach himself architecture by devouring the reading list of university architecture students. What was meant to be read over the course of four years took him only one. Additionally, he took distance education courses in drawing to prepare himself for his profession.

His stubbornness and tenacity have stayed with him throughout the years, allowing him to pursue the singular vision that defines his architecture. His architecture practice, which he began in 1969, is still based in Osaka, bucking the convention that pushed architects to go to Tokyo to find success. While much of his work is in and around Osaka, he’s also branched out overseas with several big projects, including the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth in Texas and 152 Elizabeth, a residential tower in New York City.

So what defines Tadao Ando’s architecture? Inspired by architects like Le Corbusier and having immersed himself in great classical architecture, he’s continually striving to create and transcend what has come before. “The real importance of architecture is its ability to move people’s hearts deeply,” he shared in an interview with PORT Magazine. “I am always trying to establish spaces where people can gather and interact with one another.”

Tadao Ando at the opening of the Langen Foundation’s art exhibition house, 2004. (Photo: Christopher Schriner from Köln, Deutschland (flickr: Tadao Ando) [CC BY-SA 2.0 ], via Wikimedia Commons)

Characteristics of Tadao Ando Architecture

Materials

Church of Light, 1989. (Photo: Sira Anamwong via Shutterstock)

One of Tadao Ando’s defining characteristics is his use of concrete. What distinguishes his use of this common material is the smooth, almost reflective finish he’s able to achieve. Combined with bare, minimalist walls, this allows him to bring focus to the form of the building, as this is what he believes brings emotional impact to architecture. Ando achieves his characteristic concrete finish by varnishing the forms before pouring begins.

His iconic Church of Light, built in 1989 and located just outside Osaka, is a prime example of the power of simplicity. Composed of a cement box perforated by light coming through a cruciform slit, it’s a work that Ando once said embodied the key principles of his architecture practice.

Geometry

Row House in Sumiyoshi, 1976. (Photo: Oiuysdfg [CC BY-SA 3.0 ], from Wikimedia Commons)

“I believe that the emotional power in architecture comes from how we introduce natural elements into the architectural space. Therefore, rather than making elaborate forms, I choose simple geometries to draw delicate yet dramatic plays of light and shadow in space.”

This guiding philosophy is ever present in Ando’s work. His 1976 Row House in Sumiyoshi, or Azuma House, is an early work that shows the impact of his mastery of shapes. The small personal home consists of two concrete rectangular volumes without exterior windows that give way to a rectangular outer courtyard to provide an oasis from city life.

Nature

Hill of the Buddha. (Photo: YouTube) READ MORE: Giant Buddha Is Surrounded With Harmonious Mound of 150,000 Lavender Plants

For Ando, architecture is at its best when it allows people to experience the beauty of nature. “Architecture is not a self-independent individuality. In my opinion, it comes to existence only through relation to various elements of the surroundings like water, green, light or wind,” he shared in a 2014 interview with The Glass Magazine.

This continuity of indoor and outdoor space is a principle typical of Japanese culture and Ando takes this philosophy to new heights by incorporating modern touches. His work at the Makomanai Takino Cemetery in Sapporo, where he framed a 44-foot-tall Buddha in a lavender hill, highlights how he uses nature to guide people’s experience with the space.

Water is a recurring theme in Ando’s work. In Fort Worth, the museum is surrounded by an expanse of water that reflects a second vision of that architecture that is, for Ando, just as much a part of the work as the physical building. By using water and light, he is also able to introduce movement to his work, as well as an ephemeral quality achieved by how the water changes throughout the course of the day.

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, 2002. (Photo: T Photography via Shutterstock)

Light

21_21 Design Sight, 2007 (Photo: Sira Anamwong via Shutterstock)

In keeping with Ando’s minimalist aesthetic, his use of light allows him to subtly guide the mood of each building. Whether it’s the powerful burst that breaks through the cement of the Church of Light or the play of light and shadow in Tokyo’s 21_21 Design Sight, his strategic use of natural light is a hallmark of his style. With sparse interior decoration, people are left to ponder the space and the passage of time via the changing light dynamics within his architecture.

Space

Hyōgo Prefectural Museum of Art, 2002. (Photo: Off Bombs via Shutterstock)

“When I design buildings, I think of the overall composition, much as the parts of a body would fit together. On top of that, I think about how people will approach the building and experience that space… If you give people nothingness, they can ponder what can be achieved from that nothingness,” he told Architectural Record.

Ando’s desire to help people reflect on their inner selves rather than focus on the outward visual is just one way the Japanese Zen philosophy manifests itself in his work. The architect acts as a guide, creating strategic pathways through his architecture that allows visitors to meditate on the shapes and forms without distraction. His meticulous use of space and his emphasis on the physical experience of architecture is a large part of what has made him one of the greatest architects of our time.

Awaji-Yumebutai, 2000. (Photo: Part-Time Traveler via Shutterstock)

Learn more about Tadao Ando’s architecture in Taschen’s Ando: Complete Works: 1975-Today.

Related Articles:

Mountainside Memorial Features 100 Blooming Gardens That Change with the Seasons

Zaha Hadid’s Legacy and Her Top 10 Architectural Masterpieces

10 of the Most Iconic Buildings by Architect Frank Gehry You Should Know