Photo: Stock Photos from Massimo Salesi/Shutterstock

Each June, the LGBTQIA+ community comes out in full force to make their voices heard. Pride Month is a time of celebration and a time for activism. And while so many important victories have been won by the gay community in the last few decades, it wasn’t so long ago that things were quite different. Yet, one night sparked a fire that would change the course of history. Thanks to the 1969 Stonewall Riots, a community was brought together and a new wave of activism took hold that would propel change and put civil rights at the forefront.

Often called the Stonewall Rebellion or the Stonewall Uprising, the events that took place on June 28, 1969 would change how the gay community was treated across the United States. Fed up with harassment and abuse by law enforcement, a group came together in New York City to make their voices heard. Tired of peacefully asking for change, they banded together and took action to make things right.

What happened that evening in Greenwich Village at the Stonewall Inn, a small gay bar on Christopher Street, had repercussions that can still be felt today. Every gay person who enjoys a life living their truth without having to hide can give thanks to the men and women who put themselves at risk to show that they weren’t going to stand down and be mistreated.

Let’s look at what led up to the Stonewall Rebellion and how it changed American history in order to understand both how far we’ve come and how far we still have to go.

Photo: Stock Photos from lazyllama/Shutterstock

The Gay Community in 1960s NYC

In the 1960s, homosexuality was still listed as a mental disorder by the American Psychiatric Association and many people lost their jobs if they were suspected of being homosexual. After World War II, the American government viewed homosexuality as an act of perversion and that these people, who were not “normal,” could pose a security risk.

Law enforcement kept lists of homosexuals and their activities were tracked. Sweeps of city neighborhoods to rid them of gay people were routine. In New York City, Greenwich Village and Harlem were the hubs of large, active gay and lesbian communities. Police raids were common in the city, particularly leading up to the 1964 World’s Fair, when the mayor had concerns about the city’s image. Liquor licenses for gay bars were pulled and undercover officers aimed to entrap gay men so that they could be charged with solicitation.

The Gay Bar as a Place of Refuge

Things settled down somewhat after 1965, when an early gay rights group—the Mattachine Society—campaigned the city’s new mayor to stop entrapment. Still, members of the community were often harassed. This made gay bars one of the few places of refuge where people could go out, relax, and meet other like-minded people.

But, even at the gay bar, all was not as it seemed. None of these bars were owned by gay people. They were almost all owned by members of the Mafia, who were able to pull liquor licenses and pay off the police so that their clientele could mingle in peace. In the case that there were raids, owners were usually tipped off and they often occurred at the beginning of the night when there were few clients. This way they could continue earning for the rest of the night. The downside to this was that drinks were often watered down and overpriced and the staff was often mistreated.

When raids did happen, people were lined up against a wall and asked to produce identification. Anyone who had an ID that did not match up with their presenting gender was immediately arrested. This included women who weren’t wearing at least three “appropriately female” items of clothing, drag queens, and transgender men and women.

A Raid in the Early Morning Hours

On Saturday, June 28, 1969 it was business as usual at the Stonewall Inn. Employees have no recollection of being tipped off about a police raid, so when four plainclothes officers, two patrol officers, a detective, and a deputy inspector entered at 1:20 am and declared that they were taking hold of the bar, it was a surprise to everyone.

Earlier in the evening, four undercover officers—two men and two women—had entered the bar to gather visual evidence and once the sign was given, reinforcements entered. The lights were turned on and the bar’s 205 patrons were caught in the confusion. As the police had barred the doors, there was no escape.

Officers tried to get on with the usual procedure of these raids—have everyone line up in rooms by their presenting gender and show ID. But this time, things didn’t go as planned. Stonewall’s clientele did not show signs of cooperating—men dressed in drag refused to go with the officers and many refused to show identification.

Maria Ritter, a transgender woman whose family still knew her as male, was at the bar and remembers her concern. “My biggest fear was that I would get arrested. My second biggest fear was that my picture would be in a newspaper or on a television report in my mother’s dress!”

Eventually, the police separated everyone who was dressed in clothing not conforming to their gender into another room and decided to bring everyone to the station. Other patrons were free to leave, but instead of dispersing quietly, they assembled outside of the bar. Many called friends to make them aware of what was happening and the crowd grew larger.

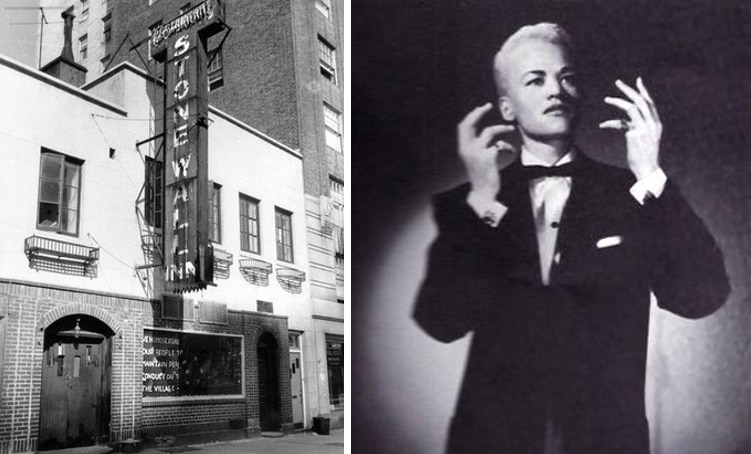

Left: Stonewall Inn in 1969 (Photo: Diana Davies, copyright owned by New York Public Library, CC BY-SA) | Right: Stormé DeLarverie (Photo: Wikipedia)

“Why don’t you guys do something?”

The police were often forceful with the crowd, but many patrons began to make a performance in front of the police by posing and making exaggerated movements. This was cheered on by the crowd, which only pumped up the crowd. Chants of “Gay Power!” moved through the crowd and an edge of hostility took over.

The crowd threw beer bottles at the patrol wagon and cheered on a drag queen as she hit an officer over the head with her purse after being shoved. The tipping point came when a woman in handcuffs, often identified as lesbian entertainer Stormé DeLarverie, was hit on the head with a baton when she complained that her restraints were too tight. After escaping repeatedly and scuffling with the officers, she shouted to the crowd, “Why don’t you guys do something?”

That is when violence broke out, with the crowd advancing toward the police. Outnumbered by 500 to 600 people, police officers were forced to barricade themselves in the bar for safety. Bricks were hurled and windows were broken, with the bar eventually being set on fire.

The uprising continued for the next five days as a spontaneous response to the outrage that had been building within the community for years due to discrimination and mistreatment.

Michael Fader, who was at Stonewall that evening, explains what led to the riots:

“We all had a collective feeling like we’d had enough of this kind of sh*t. It wasn’t anything tangible anybody said to anyone else, it was just kind of like everything over the years had come to a head on that one particular night in the one particular place, and it was not an organized demonstration… Everyone in the crowd felt that we were never going to go back. It was like the last straw. It was time to reclaim something that had always been taken from us… All kinds of people, all different reasons, but mostly it was total outrage, anger, sorrow, everything combined, and everything just kind of ran its course. It was the police who were doing most of the destruction. We were really trying to get back in and break free. And we felt that we had freedom at last, or freedom to at least show that we demanded freedom. We weren’t going to be walking meekly in the night and letting them shove us around—it’s like standing your ground for the first time and in a really strong way, and that’s what caught the police by surprise. There was something in the air, freedom a long time overdue, and we’re going to fight for it. It took different forms, but the bottom line was, we weren’t going to go away. And we didn’t.”

Photo: Stock Photos from Christopher Penler/Shutterstock

Why the Stonewall Inn?

Many gay bars faced unexpected raids during this time, so what was it that made the Stonewall Inn so special? To truly understand, one must look at the context of the time. During this period, the LGBTQIA+ community was very divided. Many gay bars would not let lesbians, queens, overly effeminate men, or transgender patrons through their doors. Some of the bars were also simply too expensive for those without a solid income. Stonewall was different.

More than just a bar, it was the touchstone for marginalized members of the community. “The ‘drags’ and the ‘queens,’ two groups which would find a chilly reception or a barred door at most of the other gay bars and clubs, formed the ‘regulars’ at the Stonewall,” recalled Dick Leitsch a journalist and executive director of the Mattachine Society. “To a large extent, the club was for them… Apart from the Goldbug and the One Two Three, ‘drags’ and ‘queens’ had no place but the Stonewall.”

Leitsch points out that Stonewall also catered to a large, but often ignored, part of New York’s gay population—young, homeless men. With so many young boys kicked out of their homes after their homosexuality was revealed, they flocked to the city in droves. Ranging from age 16 to 25, they arrived without money, a job, or a roof over their heads. For just $3, anyone could enter Stonewall for the night and get two drinks. These youths would panhandle during the day to make their admission money and then spend the evening in the safety and warmth of Stonewall.

In this context, it’s easy to see why the Stonewall Inn was much more than a bar to this community. And it’s also easy to see why these overlooked members of the population had enough built-up frustration to take a stand.

Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade, 1970. (Photo: Kay Tobin via NYPL)

The Impact of the Stonewall Rebellion

The Stonewall Rebellion was a turning for the gay community, not only in New York and the United States, but internationally. In the aftermath, a new sense of activism took hold—one that was more radical. Gay rights groups like the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis had existed since the 1950s but took a softer approach. Not only did they purposely use vague names to mask their real purpose, but they catered specifically to gay men or lesbians without ever mingling.

After the events at Stonewall, there was a noticeable shift in approach. Stonewall brought about solidarity in the community and, for the first time, associations that mixed gays, lesbians, and trans people were formed. The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) were two groups created in the aftermath of the Stonewall Uprising that placed their queerness front and center in their names.

Aside from organizing public protests, members of these groups would stage confrontations with politicians in public forums in an effort to press them about civil rights. This required politicians to be put on the spot about issues facing the gay community and give their responses publicly, often on camera. This, along with disruptions to public meetings, pushed the boundaries for acceptance from the establishment and helped set a trend of non-discriminatory policies from the 1970s onward.

The Birth of Pride Month

The Stonewall Rebellion also gave birth to Pride Month. June 28, 1970 was named Christopher Street Liberation Day to mark the first anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion. There was a large assembly by the Stonewall Inn, as well as simultaneous marches in Chicago and Los Angeles. These would be the first Gay Pride marches in the United States.

Marchers in New York would cover 15 city blocks, waving banners and carrying signs to display their pride. The Village Voice reported the scene, calling it “the out-front resistance that grew out of the police raid on the Stonewall Inn one year ago.”

New York Pride Parade 2019. (Photo: Stock Photos from Ryan Rahman/Shutterstock)

The following year, marches took place in additional U.S. cities like Boston, Dallas, and Milwaukee. There were also international marches in Berlin, Paris, London, and Stockholm. As gay activism continued to grow in the years that followed Stonewall, it became clear that this event was a galvanizing moment in the fight for gay rights.

This was only reinforced by the Stonewall Inn’s placement on the National Register of Historic Places in 1999 and President Obama’s designation of the site as a national monument in 2016.

The Stonewall Rebellion is a turning point in both American history and the gay rights movement. Sparked by outrage, it tipped the scales and called a community into action by having them band together and fight against discrimination.

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

92-Year-Old Mother Has Carried Same Sign at NYC Pride for 30 Years

Powerful Portraits and Stories of People Affected by the Pulse Nightclub Shooting

10 LGBTQ+ Makers on Etsy Crafting Creative Products During Pride Month and Beyond

Woman Hangs 10,000 Rainbow Christmas Lights in Response to Anti-LGBTQ Neighbor