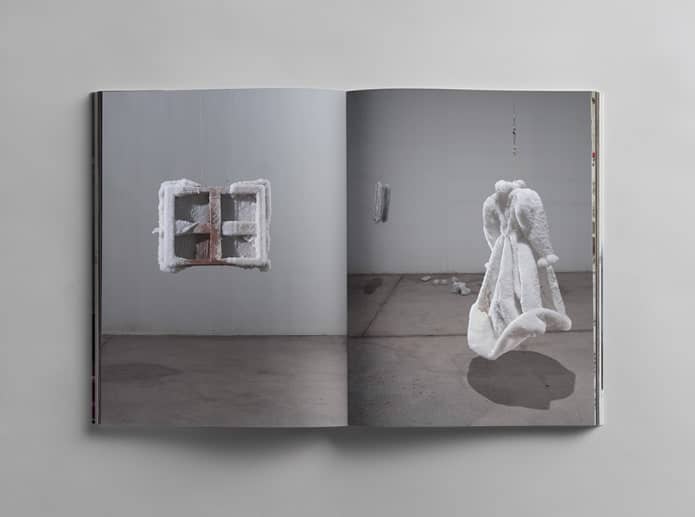

Landau with new salt sculptures, July 2016. (Photo: Shaxaf Haber)

Interdisciplinary artist Sigalit Landau‘s work is that of mystical transformation. Born in Jerusalem, the Israeli artist has spent the last 15 years of her artistic career immersed in the beauty of the Dead Sea. And now, after a year of writing, Landau, along with partner Yotam From, is paying tribute to this phase of artistry with the book Sigalit Landau: Salt Years.

Over almost 300 pages, we’re invited into the intimate world of Landau. New performances, documentation, and text reveal glimpses of her creative process as she explores the depths of the Dead Sea and its connection to history, found everyday objects, and the body. Through Salt Years, Landau invites us to take part in her transformation of the Dead Sea into her personal laboratory—a space for new ideas and experiments.

Currently available for pre-order via Indiegogo—including signed and limited deluxe editions—the book is filled with texts by philosophers, art historians, and geologists who all give unique perspectives on Landau’s 15-year adventure. We had the chance to ask the renowned artist some questions about her relationship to the Dead Sea and how she feels about this chapter of her career. Read our exclusive interview below.

‘When I go,’ 2017, Furniture and readymades, cello, veil, suspended in the water of the Dead Sea. (Photo: Yotam From)

What attracted you to the Dead Sea as an artist?

The Dead Sea attracted me as an artist because I believe that it is a place where truth and spirituality are in a way “tangible.” The different rules of gravity and light, beauty and sterility, and a lot of childhood memories are what brought me time and time again to create, experiment, shoot, sail, and crystalize memories in this one lake.

In 2002, just before my mother’s death, I exhibited a show called The Country in the basement of a Tel Aviv gallery depicting allegorically with Dionysian urgency—a world of bloodbaths taken from the second intifada terror attacks of those days.

In that installation, which was impactful, I used agriculture, a fundamental theme in Zionist identity, agenda, and practice, with the return to the land as “new-Jews,” in a metaphoric way—and the scene I depicted there was a harvest of red fruit which I made from daily newspapers.

A year later, after losing my mother, I looked for a less allegorical fruit and more physical presence … my search ended when I discovered the findings of desert-water researchers regarding watermelons. Watermelons are sweeter and with a thinner rind if they are watered with undrinkable saline water from wells which are located in the Arava desert, not far from the southern part of the Dead Sea.

Testing for snow…salt crystals in the Dead Sea, 2004. (Photo: Studio Sigalit Landau)

You’ve spent 15 years with the Dead Sea as an integral part of your work, what does it mean to you to see it culminate in Sigalit Landau: Salt Years.

We used to have engraved black records, and we put them on and at the end of each LP side A you’d hear the diamond needles “scratch” rhythmically, the pointless analog “itch”—this moment that if you don’t get up and change sides…

The idea is: I am turning the record over by making this book … which is about the sea and its fate and most of all about our partnership, and Sigalit Landau: Salt Years shows the ongoing teamwork, which I feel the need to share and is highly significant. The book is a big undertaking. Perspective is something we all hope for, and in this publication, at least one important layer will become accessible, so that the stage is ready for the second act.

Landau and From after lifting a new work, July 2016. (Photo: Shaxaf Haber)

For fans of your work, what can they expect to see in the book?

I hope Salt Years will encompass my personal, colorful experiences exposed—very physical and visual. Texts, which I have been longing for, take a close and thorough look at several aspects. This kind of attention to a specific site for 15 hard years is a labor of love that an exhibition may sometimes hide and institutions may not dare/care enough to get involved with.

Remember Francois Truffaut’s film The 400 Blows? I came to the sea to “rest my case” and there I found no rest, but a treasure for a studio—my case exactly. I hope that Salt Years will offer insights and a better understanding of the beautiful work process. Also, for me the book is a diary. Diaries are especially needed by those contending with the idea of home, walls, institutions—a book is a layered creation which is a time map, a weight, an experience which captures time in a very good way. It is also an object and still the best way to crystallize ideas, celebrate partnerships, cherish memories, and discover the behind the scenes and experiments which were not at all super successful.

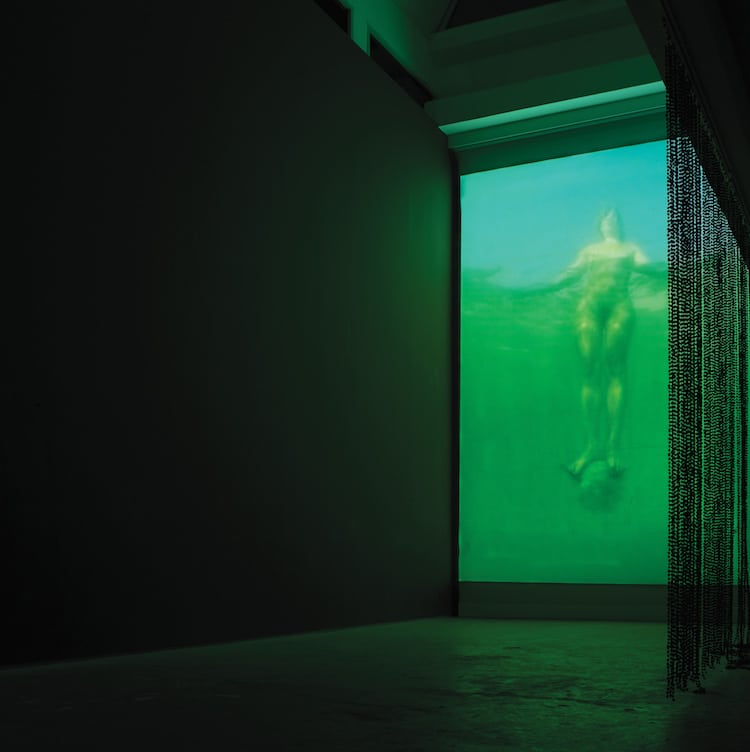

‘DeadSee’, 2005, Video, 11:39 min.

What was the first artwork you produced in the Dead Sea?

After spending some years working and passing by the British, French, Berlin, New York art worlds, on the move, hardly affording a house—let alone a studio—in 2003 my mother died. I had just been commissioned to do a large show in the Tel Aviv Museum in an autonomous pavilion called the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion—donated to the young city of Tel Aviv by Rubinstein in the mid 60’s.

My work at the Dead Sea started in this show which was called The Endless Solution; My first, and most well-known video works, were made for this exhibition; DeadSee, Dancing for Maya, Standing on a Watermelon, Under the Dead Sea—and I started working with crystals and learning what the “rules of the shore” were in this rediscovered ex-territory.

‘The Endless Solution’ [installation view], 2005 (Photo: Oded Lobel)

As a site-specific artist, trying to somewhat ignore the anecdotal mundane reality and facts, I think due to the death of my mother, I started my journey to the “Red Rock” [Petra, Jordan] by reading and translating into drawings my experience of the Judea, Arava, and Negev desserts in combination with the life story of Helena [of Troy + Mrs.]. Anti-Aging, and in parallel to my mother’s legacy (post-World War II immigrant to Israel via being born in London, daughter of Viennese intellectuals, refugees, who stayed to live in, and died in London).

My experience was formulated while taking into account all of these revelations and many more—I saw no other way: it was Tel Aviv which needed to be ‘woken up’ to my storytelling so that I could free fall into this very real ‘hole’ [rift valley] in time: my memories were so different than what Tel Avivian’s were trying to do and be. Rather than rotating around the sun: I asked the sun to rotate around “The Desert,” planet Jerusalem, the hole.

In 2016, your work Salt Bride received an incredible amount of attention. What do you think it was about that piece in particular that captured the public’s imagination?

In 2016, your work Salt Bride received an incredible amount of attention. What do you think it was about that piece in particular that captured the public’s imagination?

That a bride can be from salt and not from sugar. That the past can be transformed so drastically and nature so healing. That a place writes your identity so boldly in this area…

First research trip, 2003. (Photo: Studio Landau)

Is Salt Years an end to your installations in the Dead Sea or just the beginning of a new chapter?

Beginning of a new chapter!

Still fascinated, I hope to turn a new page in my work-life after publishing Salt Years. My new video scripts and performances, all my proposals, are involved to some extent with the Dead Sea and also with the ecological concerns, I want to help make big changes happen. I want to be able to grow!

Tutu ballet dress rising from the water of the Dead Sea 2016. (Photo: Shaxaf Haber)

Sigalit Landau: Website | Instagram | Indiegogo

My Modern Met granted permission to use photos by Studio Sigalit Landau.

Related Articles:

12 Contemporary Artists Tell Us What it Takes to Make a Great Piece of Art

What is Installation Art? Take a Look at the Top Installation Artists Working Today

10 Cutting-Edge Artists Who Use the Human Body as a Canvas

Meet the Innovative Artists Who Pioneered Performance Art and Elevated Its Importance