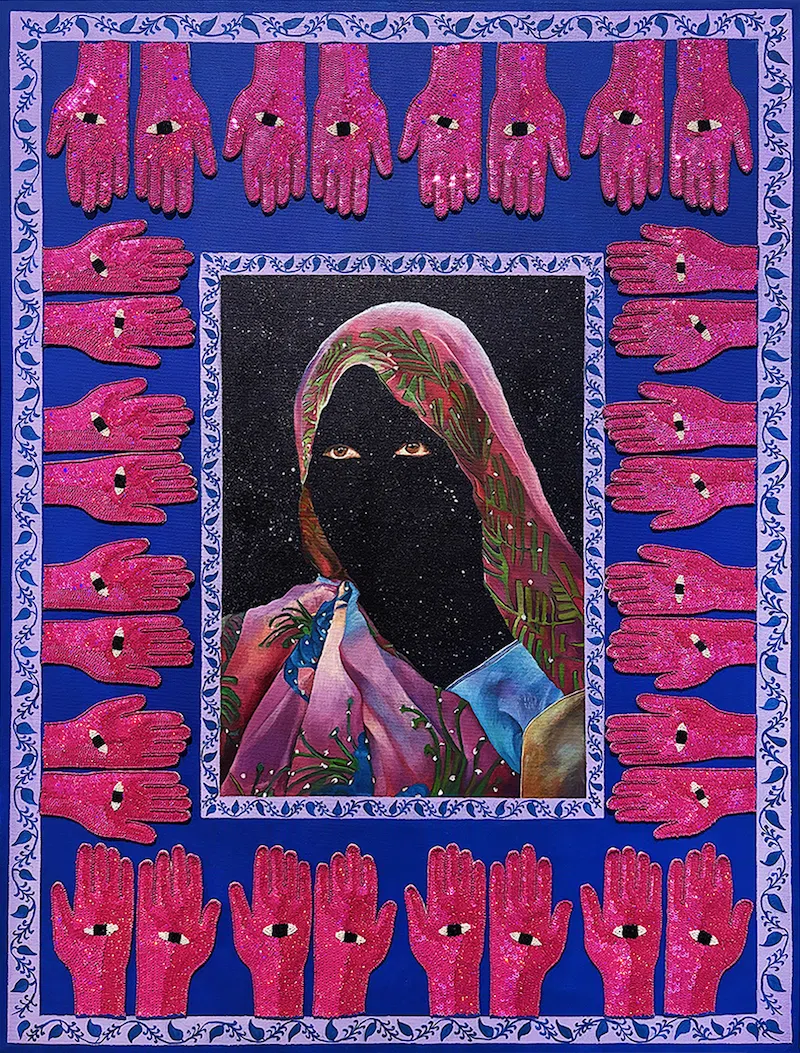

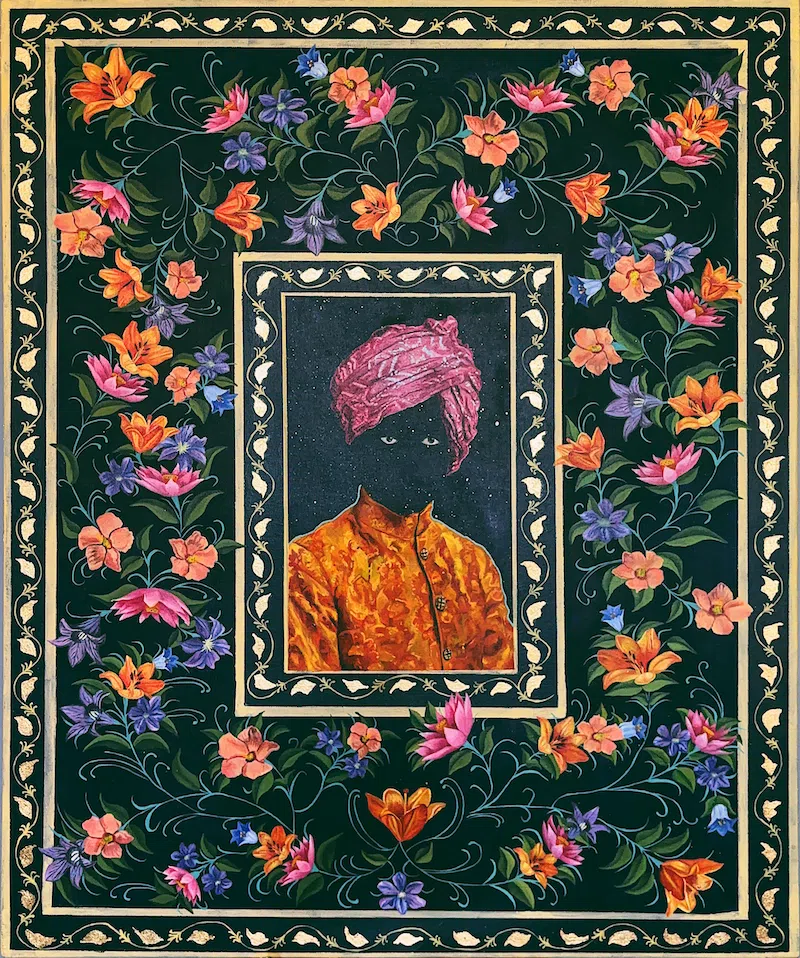

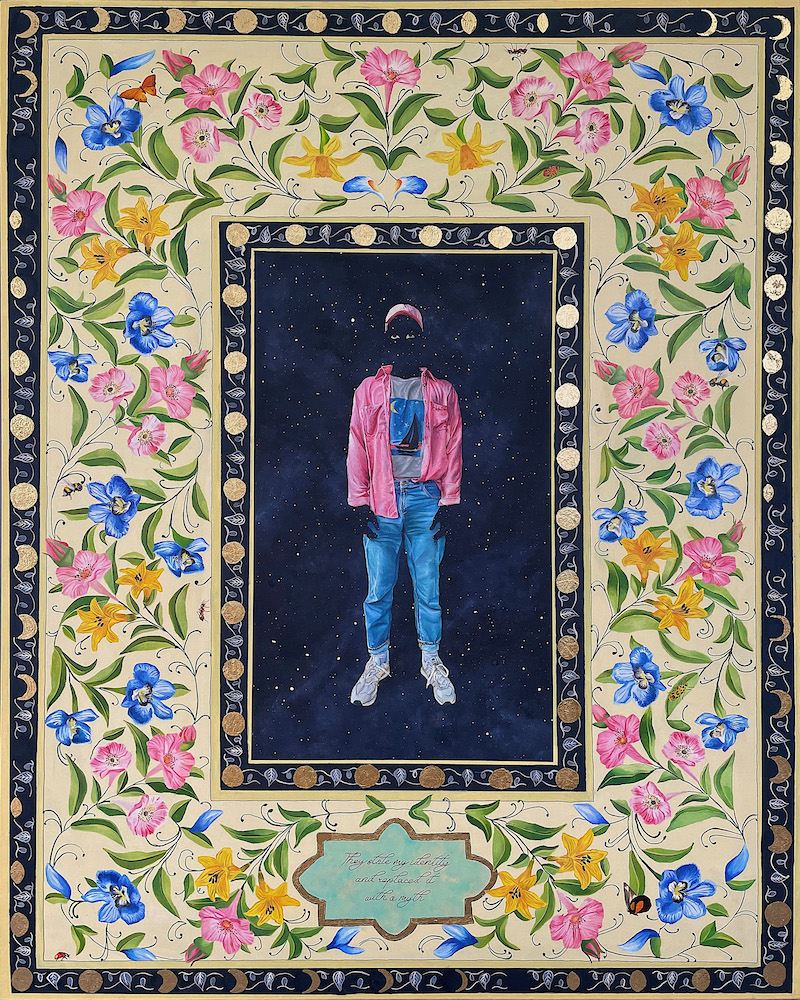

“A fly in the milk II”

Throughout the three years that he attended art school, Sid Pattni never learned how to paint his own skin tone. Representing white skin came more naturally to him than brown skin, and it was only after his program that he began questioning why. It was at this point that the Australian artist laid the foundations for his creative practice, veering toward post-colonial frameworks that could more adequately address his concerns with diaspora and displacement.

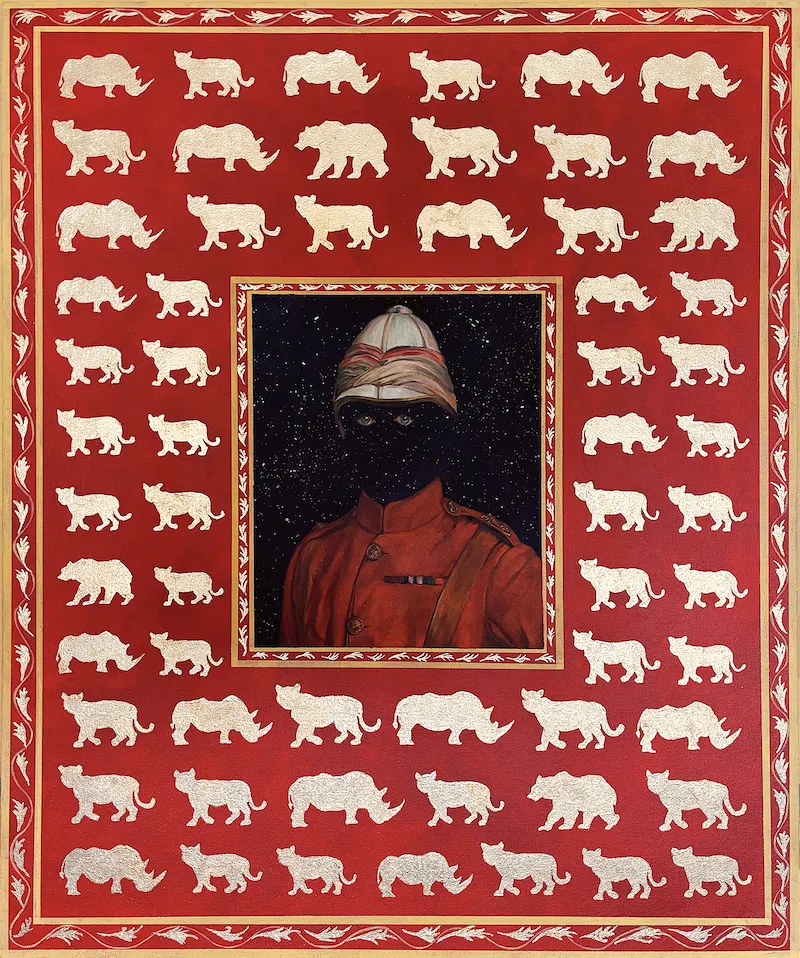

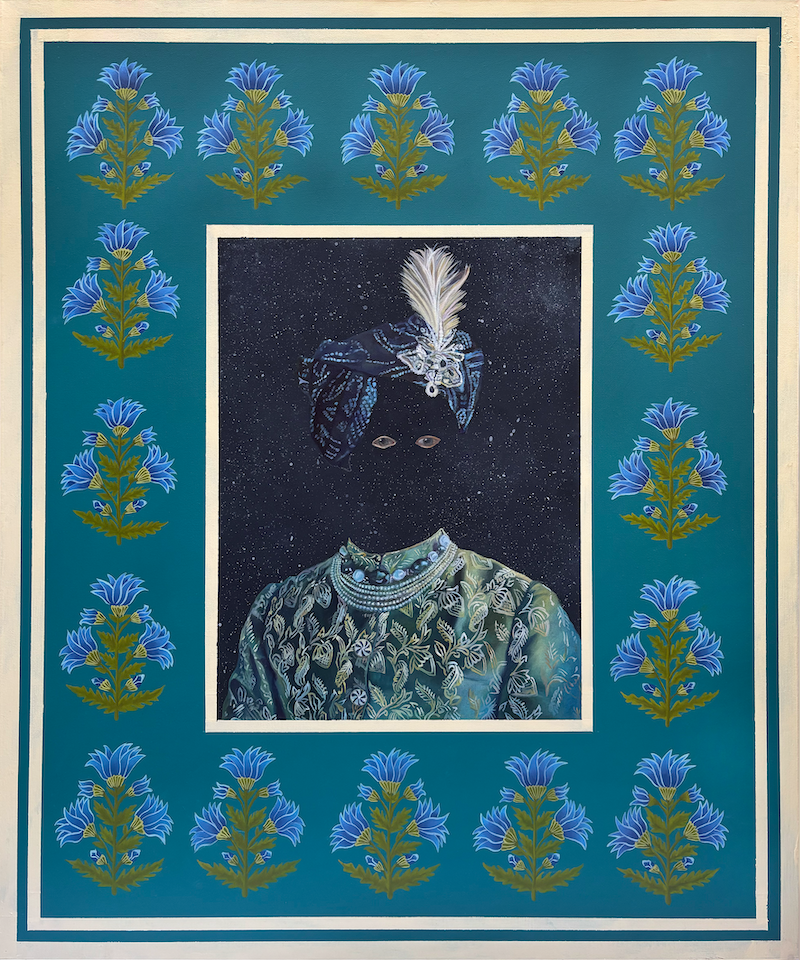

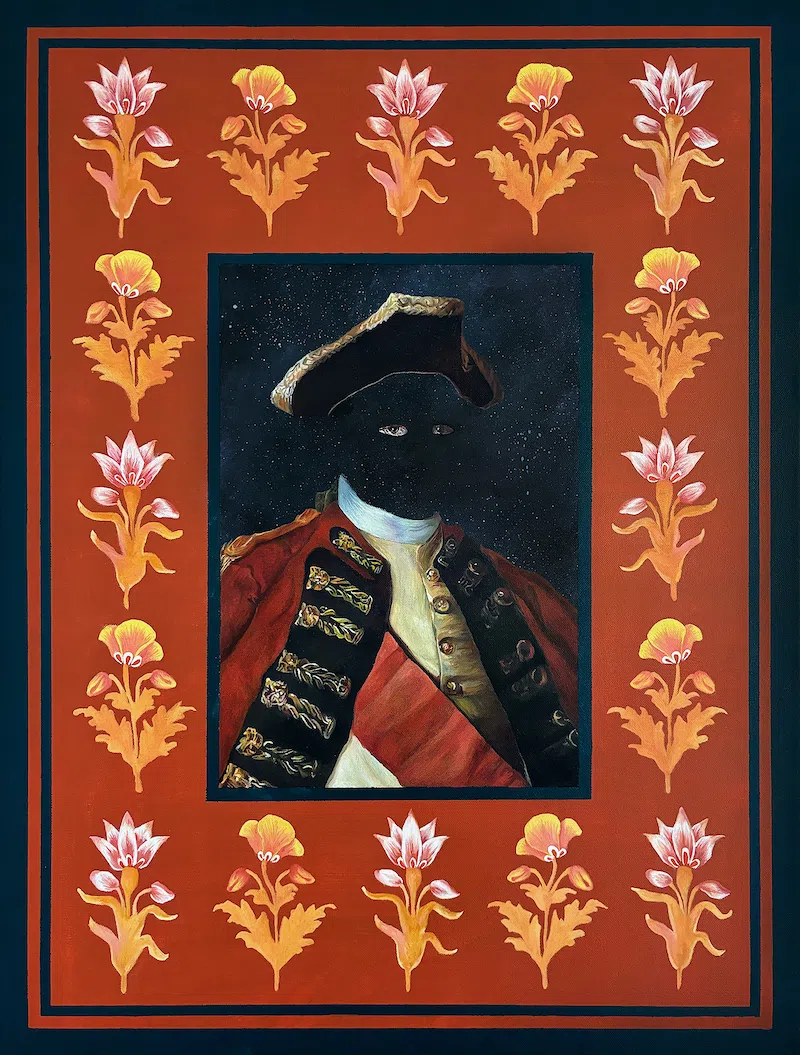

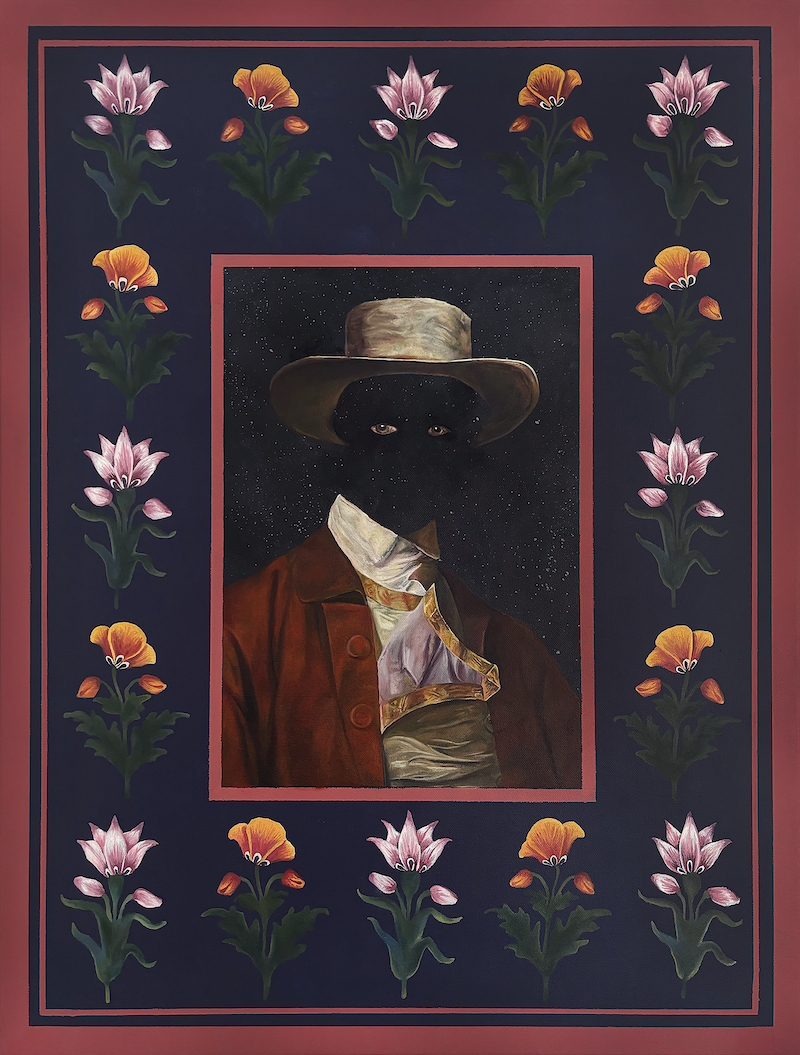

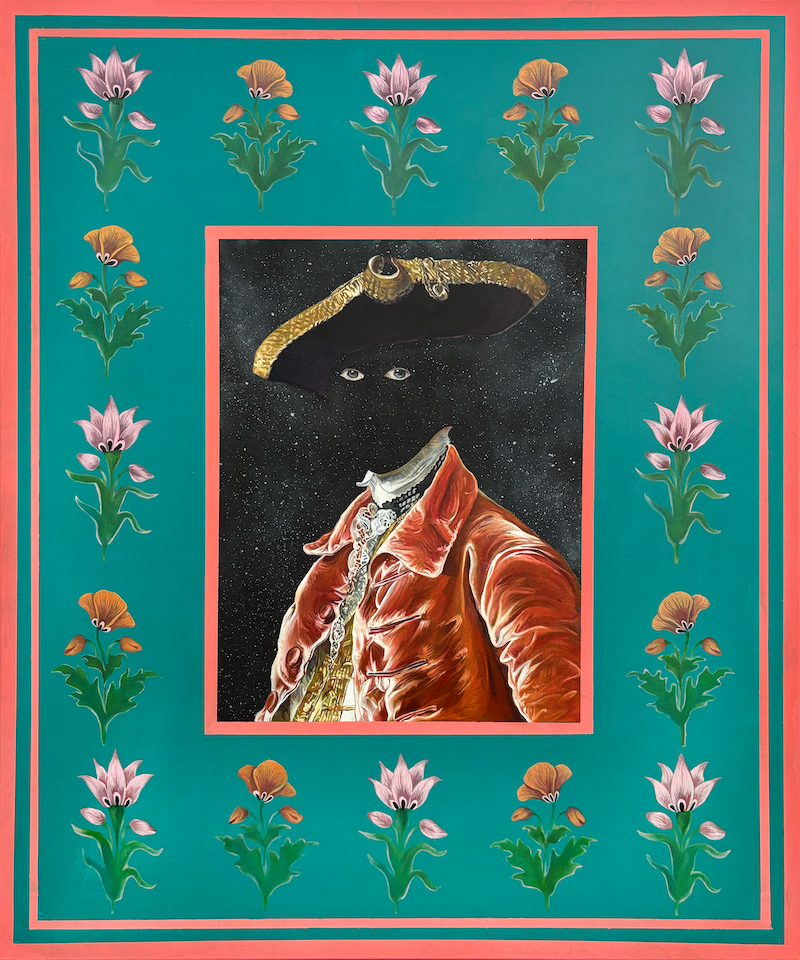

Today, Pattni has become known for paintings that resurrect images of empire, all while “dismantling and reconfiguring” the aesthetic languages upon which they rely. Most times, that “dismantling” takes the form of Mughal miniatures, an artistic tradition from South Asia that often features flat coloring and characters, floral borders, and epic motifs. Pattni’s miniatures may revolve around these stylistic elements, but they also incorporate colonial figures that are stripped of their faces rather than being gifted an identity. The juxtaposition is striking: vibrant, lavishly patterned frames circle around black voids at the center of Pattni’s canvases. Here, we see no traces of empire, except for tiny eyes peering out from the darkness.

“By addressing the visual legacies of empire, my work seeks to expose the shared tactics of control, categorization, and representation that underpin colonial systems globally,” Pattni tells My Modern Met. “I hope my paintings serve as an invitation for reflection—on how identity is constructed and contested.”

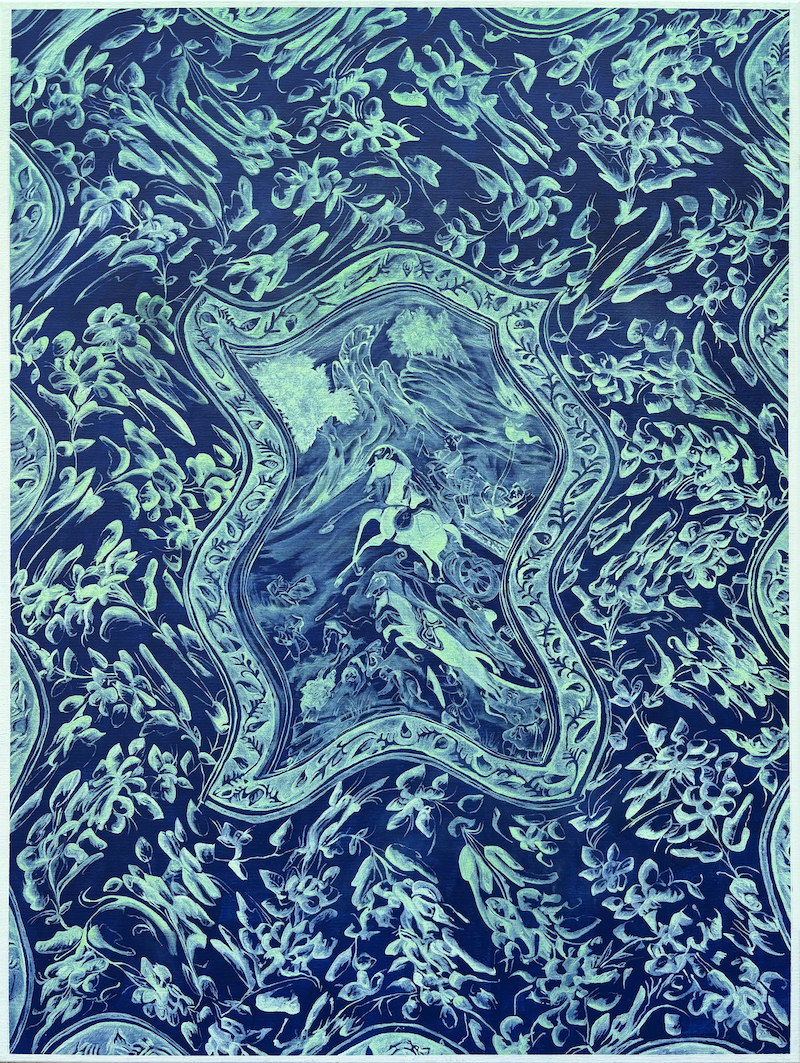

Aside from colonial portraits, Pattni also interrogates the legacy of British botanical illustrations. In his paintings, the artist references these illustrations alongside Mughal florals to create composite flowers, all of which are “deliberately mythological.”

“That impossibility is symbolic of the ways colonialism fractured cultural authenticity, creating hybrid identities that can’t be neatly categorized,” Pattni explains. “By reconfiguring both floral languages, I’m creating a visual metaphor for diasporic identity.”

My Modern Met had the chance to speak with Sid Pattni about his practice, the significance of post-colonialism in his work, and the meaning behind diaspora. Read on for our exclusive interview with the artist.

“A borrowed myth I”

What first compelled you about painting as an artistic medium?

Painting drew me in as both a material and a conceptual space. Technically, there’s something inherently tactile and immediate about working with paint—the layering, use of color, translucency and the physical labor of mark-making. But conceptually, painting carries with it a heavy historical legacy. It was both a tool of empire and a medium of resistance.

I was compelled by this tension—the potential to work within a medium that historically contributed to orientalist perceptions of India, while simultaneously using it to deconstruct and subvert those same narratives.

“A borrowed myth II”

“George’s Big Day Out”

How has your practice evolved throughout the years?

My practice has shifted from being centered around personal narrative to becoming an interrogation of broader historical frameworks. Earlier work explored my family history and migration more directly, but over time, I began to see these stories as situated within larger colonial structures that had shaped not only my family’s movement but also my own understanding of identity. I’ve moved towards working with existing visual languages—Mughal miniatures, Company paintings, British botanical drawings—not as fixed artifacts but as contested sites of meaning. My work now focuses on dismantling and reconfiguring these languages to explore how colonial power continues to shape diasporic identity today.

“A borrowed myth III”

What originally drew you to colonial history as an artistic framework?

Colonial history isn’t distant from me—it’s the architecture underpinning my identity. My family’s migration from India to Kenya, and later my own move to Australia, all sit within patterns of colonial displacement and global movement. This made me question not just personal narratives, but the structural conditions that produced them.

Visually, I was drawn to the way colonial histories were aestheticized: the orientalist gaze in British paintings of India, the cataloguing of botanical illustrations, the reduction of identity in Company paintings. These weren’t neutral representations—they were tools of control. Using colonial history as a framework allows me to critically engage with the very images that have shaped how Indians—and Indian diasporic people like myself—have been seen, and have come to see ourselves.

“A knot in the thread I”

“A fly in the milk I”

What is the significance of Indian Mughal miniatures to you, and what techniques do you use to reproduce such elements?

Mughal miniatures represent a visual language that is simultaneously familiar and distant for me—a cultural inheritance shaped by empire and aestheticized by the West.

In my work, Mughal miniatures operate as both historical artefacts and sites of disruption. I borrow their compositional structures, motifs, and perspectives, often reconstructing these through paint, textiles, and other media to speak to contemporary diasporic experience.

“A knot in the thread II”

“The prince and his burden”

What first inspired you to combine Mughal florals with British botanical illustrations, and how does this function as a form of reclamation?

The floral borders in Mughal paintings symbolized a range of themes including paradise, abundance, and cosmological order. When I juxtapose these with British botanical illustrations—products of imperial cataloguing and classification—I’m highlighting the act of appropriation inherent in colonial science and aesthetics. These composite flowers in my work are deliberately mythological: they couldn’t exist in nature.

This impossibility is symbolic of the ways colonialism fractured cultural authenticity, creating hybrid identities that can’t be neatly categorized. By reconfiguring both floral languages, I’m creating a visual metaphor for diasporic identity: something neither entirely original nor entirely imposed, but resiliently composite.

“A knot in the thread III”

“Self Portrait (the act of putting it all back together)”

How have your experiences as a member of the Indian diaspora in Australia informed your artistic practice?

As a first-generation migrant from Kenya with Indian heritage, growing up in Australia meant constantly negotiating between external perceptions and internal identity. There was a period where I actively distanced myself from my Indian heritage in an effort to assimilate.

My art practice now functions as both a reckoning with that denial and a reclamation of what was once dismissed. It’s through engaging with visual histories—Company paintings, Mughal miniatures, colonial portraiture—that I can dissect how external narratives shaped that internal conflict. My work is essentially about re-authoring the story of what it means to be Indian in a post-colonial, diasporic context.

“A knot in the thread IV”

“A well staring at the sky”

How does your artwork join a broader conversation about post-colonialism and empire, especially within Australia?

In Australia, conversations about colonialism often remain focused on British settler-colonial history, particularly in relation to Indigenous Australians. My work reflects on parallel colonial histories elsewhere—specifically in India—and how they intersect with Australian multicultural narratives. By addressing the visual legacies of empire, my work seeks to expose the shared tactics of control, categorization, and representation that underpin colonial systems globally.

Within the Australian art context, my work situates diasporic Indian identity within these conversations, encouraging viewers to consider how the afterlives of empire persist not just in land ownership but also in cultural perceptions and personal identities.

“All hail the queen”

“They stole my identity and replaced it with a myth”

What do you hope people will take away from your art?

I hope my work encourages viewers to question the visual histories they’ve unconsciously absorbed—to see colonial imagery not as a static historical record, but as active forces shaping contemporary identity. I want people to feel the tension in my work: between beauty and violence, visibility and erasure, belonging and displacement.

Ultimately, I hope my paintings serve as an invitation for reflection—on how identity is constructed and contested.

“Portrait of Marikit Santiago”

Sid Pattni: Website | Instagram

My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by Sid Pattni.

Related Articles:

Sudanese Photographer Shares Personal Experience Documenting His Country’s Ongoing War [Interview]