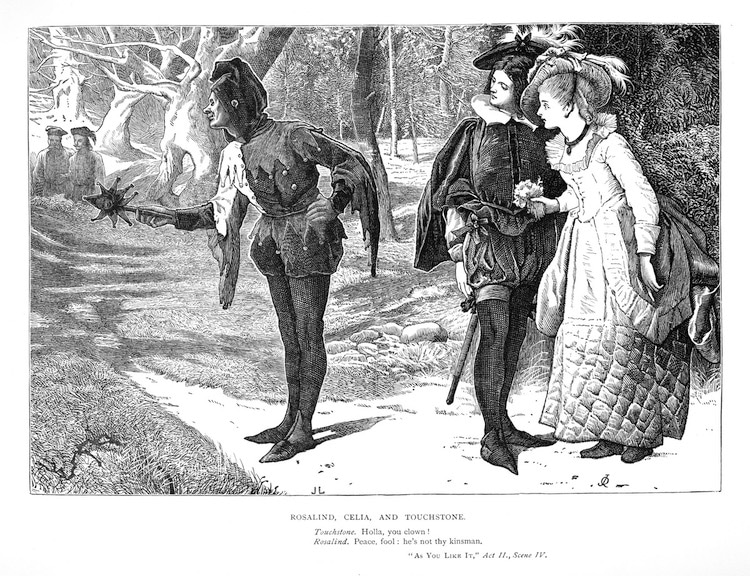

“Rosalind, Celia, and Touchstone,” As You Like It. The Plays of William Shakespeare / Edited and Annotated by Charles and Mary Cowden Clarke / Illustrated by H. C. Selous. Published 1864–68.

There is perhaps no other author as synonymous with English literature as William Shakespeare. His works—from the tragedy of Romeo and Juliet to the wicked ambition of Macbeth—continue to capture the imagination of the public. Though many academics have studied the playwright, Dr. Michael John Goodman approached his work from a new angle. As part of his Ph.D., Goodman created the Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive (VISA), a database of over 3,000 Shakespeare illustrations.

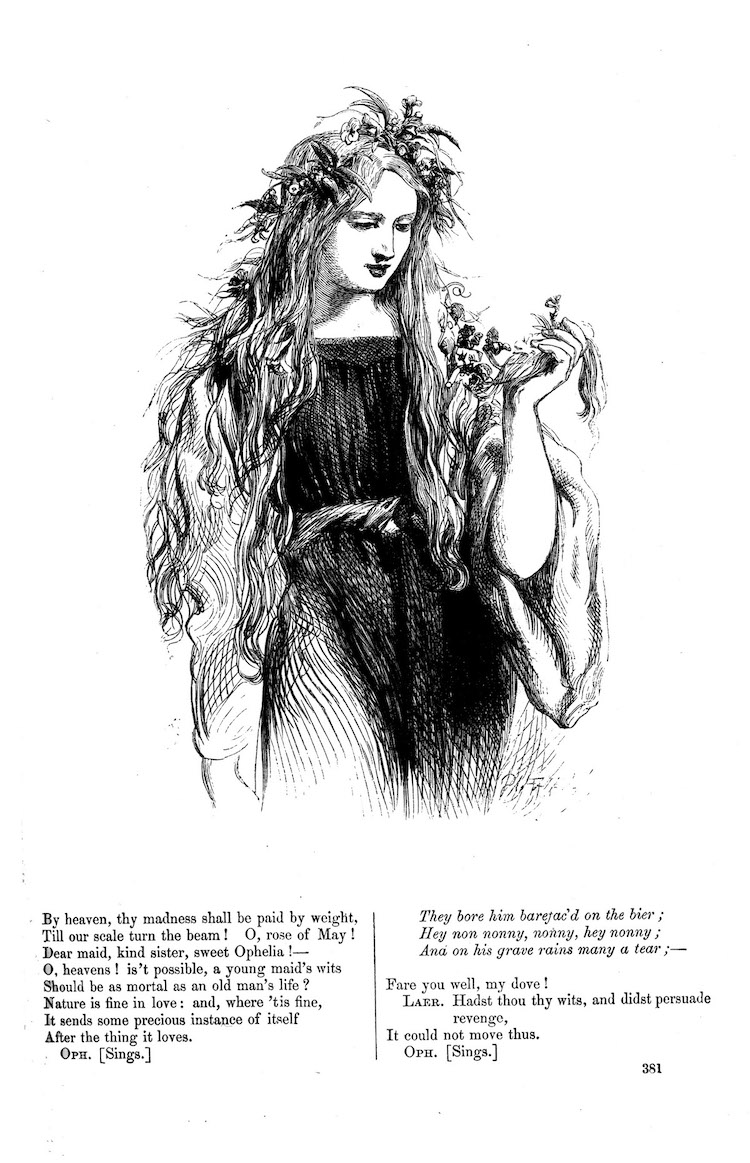

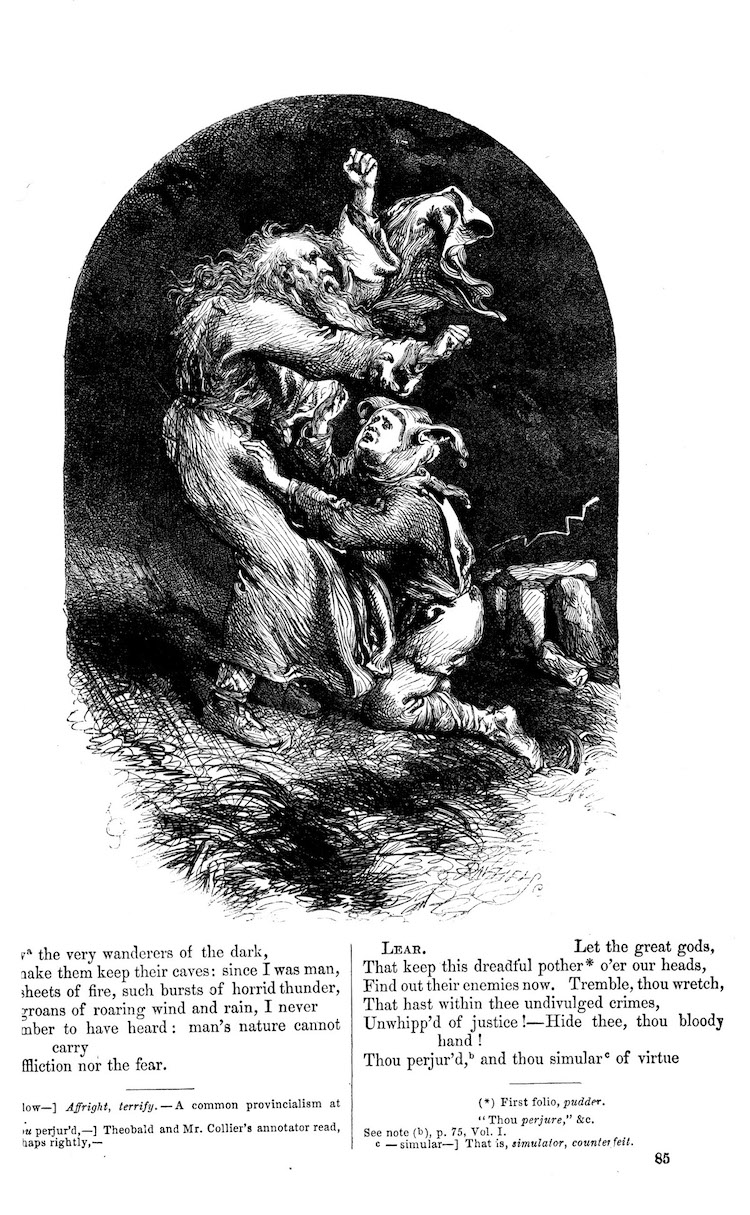

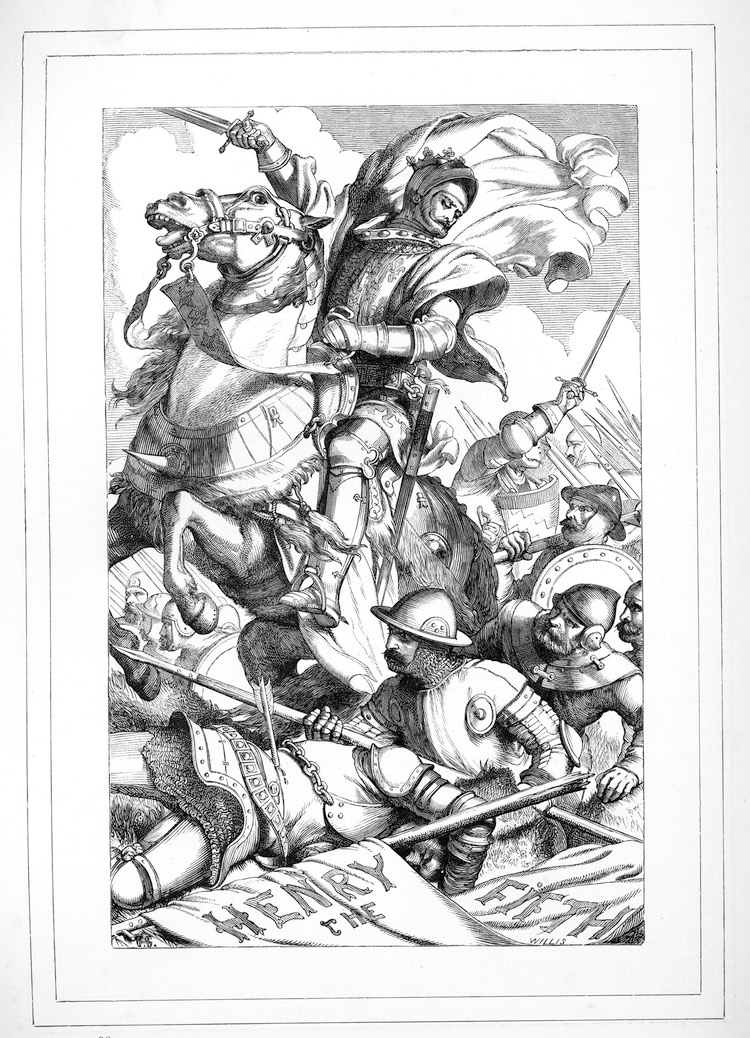

Focusing in on illustrations from the Victorian age (1837-1901), Goodman carefully scanned and cataloged images from four major editions of Shakespeare’s work produced during the period. By organizing the public domain works, he gives academics and enthusiasts the opportunity to see how artists brought Shakespeare’s words to life. Easily searchable by title, character, genre, location, and illustrator, VISA is an easy to use resource that allows for quick side by side comparisons.

Goodman, who also studied Drama in addition to English Literature, is helping a wider audience discover the joy of Shakespeare, as the Archive has been used to help high school students prepare for exams and has been featured in a short video by the BBC. We had a chance to chat with Goodman about the motivation behind his project and why he thinks Shakespeare’s legacy continues to endure. Read on for our exclusive interview.

“Ophelia.” The Works of Shakespeare / Edited by Howard Staunton / The Illustrations by John Gilbert. Published 1867.

What do you think it is about Shakespeare that makes his work so enduring?

This is such an interesting question and I think there are a couple of inter-related responses. Of course, the plays are terrific and wonderful, but the process which has made Shakespeare’s work so enduring is a bit more problematic and interesting than the quality and value we place on the plays.

“Shakespeare” as we understand him today (the pre-eminent writer in the English language) is very much a complex historical and political construct of eighteenth-century Britain. It was here in this crucible of political and cultural tensions, over a hundred years after his death, where Shakespeare became central to the British stage as well as British and—because of the Empire—global, culture.

This centrality and unique position in culture is why, whenever a new technology or medium comes out, Shakespeare is always one of the first writers to become ‘remediated’ by that new form. For example, since the invention of photography in the 1840s, photographers have sought to capture Shakespeare performances on stage.

‘King Lear and the Fool’ from The Works of Shakespeare / Edited by Howard Staunton / The Illustrations by John Gilbert / Engraved by the Dalziel Brothers / Vol. 3. Published 1867.

[continued] One of the earliest cinematic films is Herbert Beerbohlm Tree’s King John, and when the BBC first started broadcasting in 1936, Shakespeare, according to the British Film Institute, was ‘often on the menu, to give the new medium a veneer of respectability.’ In the next couple of years, I can guarantee that we shall see the same process happening again with Virtual and Augmented Reality, where the works of Shakespeare will be remediated into a new technological environment to give that medium cultural validation.

At the same time that this process is taking place, it is also maintaining and affirming Shakespeare’s centrality to society and culture. ‘Shakespeare’ always creates meaning with and is entwined and defined by the technology of the day.

“King Henry V” Introduction. The Plays of William Shakespeare / Edited and Annotated by Charles and Mary Cowden Clarke / Illustrated by H. C. Selous. Published 1864–68.

How did you settle upon this topic for your Ph.D. project?

I knew if I was going to do a Ph.D. I would want it to be innovative, exciting, and Shakespeare-based as my background is in drama and I feel very comfortable working with Shakespeare. Of course, the problem with that is that almost every aspect of Shakespeare has been written about to death!

At the time I was thinking through ideas, I was also studying a module for my M.A. about Victorian book illustration and the thought came to me that I could I could combine Shakespeare with Victorian book illustration and I could have a ready-made Ph.D. project. I knew that illustration had been on the whole critically neglected as an area of literary study and art history and I suspected that Victorian Shakespeare illustration would have been similarly overlooked, which it was.

That is not to say that people had not written about Victorian Shakespeare illustration before, but that when they had it was often an article or a chapter in a book and I wanted my project to be more extensive.

The digital aspect of the project came about as when I was doing my research. I kept uncovering a huge richness of material–a treasure trove of illustrations–which was all in the public domain and part of people’s cultural heritage. My supervisor, Professor Julia Thomas, had worked on digital archives before, so I discussed with her my ideas for creating one for Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare and her response was very positive.

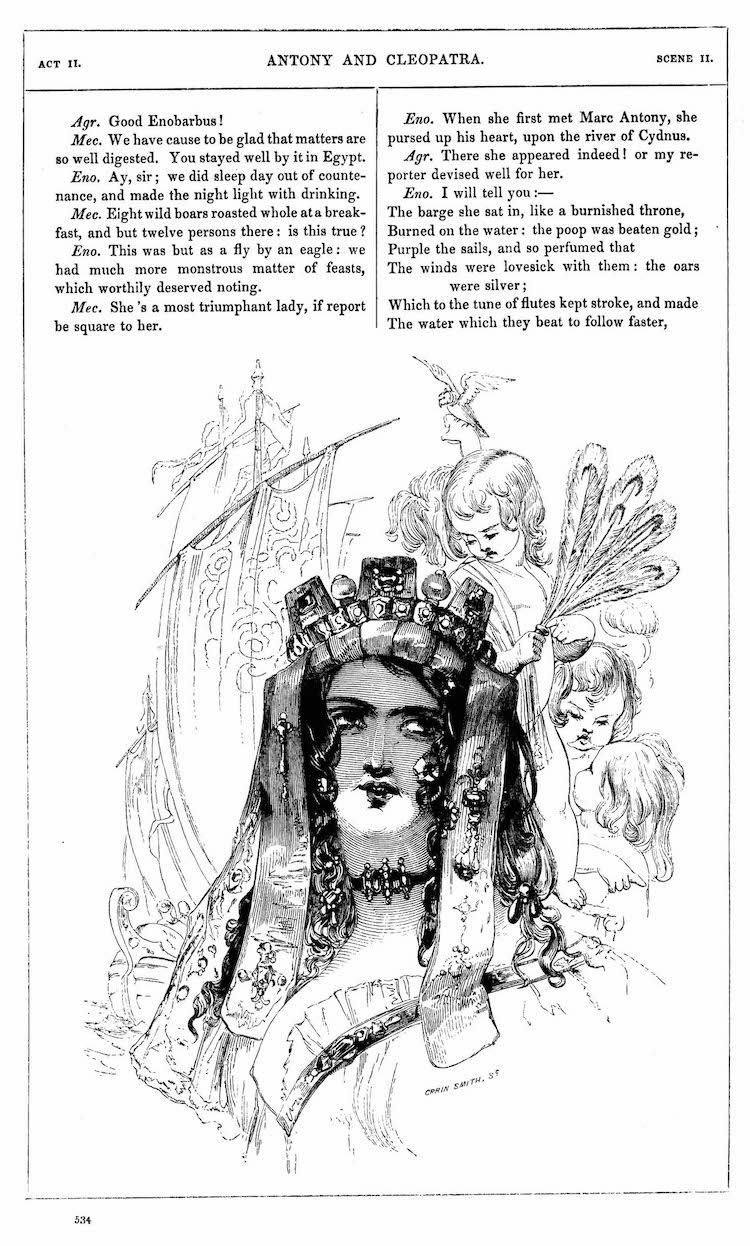

“Cleopatra.” The Works of Shakspere / Illustrated with Engravings on Wood by Kenny Meadows. Published 1846.

[continued] I wanted to create an archive that is designed for academics, students, and the wider public. In my Ph.D., I argue that a false divide has sprung up between those working in academia, who often use obfuscation as a means of alienating a wider audience to make their work seem somehow more impressive, and the public. What is particularly interesting for me is how this mindset has been ‘remediated’, in a way, into the world of the digital.

We often hear about how digital technology in universities can bring about a revolution in knowledge dissemination, but what we find is that digital resources more often than not use interfaces and designs that are difficult to navigate, or are downright archaic. There is an attitude that if we simply digitize something and stick in on the web then that is enough. It isn’t–we need to take into account the importance of design and how these digitized materials will create meaning when they are embedded within this design.

Academia, whether consciously or sub-consciously, seems to privilege gatekeeping above all else. It is an attitude I want to shake up somewhat. A valuable scholarly resource does not mean that it excludes the public, and a resource that is popular with the public does not mean it excludes academics. I hope VISA makes a positive intervention and contribution to these discussions. I want people to use the archive to share, inspire and connect – the material is there and I urge people just to play with it!

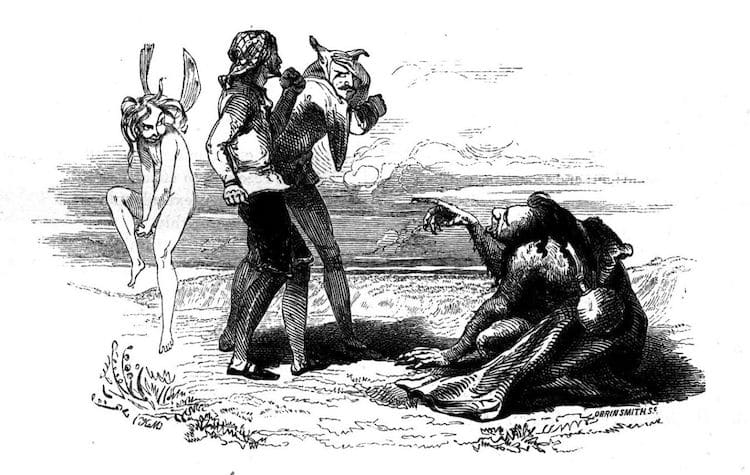

“Ariel Plays a Trick,” The Tempest. The Works of Shakspere / Illustrated with Engravings on Wood, From Designs by Kenny Meadows. Published 1846.

What was the first illustration that really grabbed your attention and why?

The first image that really grabbed my attention was the main illustration to The Tempest by Kenny Meadows. It was just so peculiar with a real unsettling undercurrent. It depicts the scene in Act III, Scene III where Ariel, acting on behalf of Prospero, enters the scene in the form of a harpy with his/her attendant spirits to scare the men from Milan who had exiled Prospero to this island twelve years ago.

What is particularly startling about the illustration, alongside the portrayal of Ariel, is the amount of unique and distinctive odd creatures Meadows’ imagination has conjured up – nothing else from this period is quite like it. Not only did this illustration startle me in how the scene was portrayed, but it also confirmed to me that my project was going to be fascinating and it gave me confidence in the extraordinary value of my material and Victorian illustrated Shakespeare.

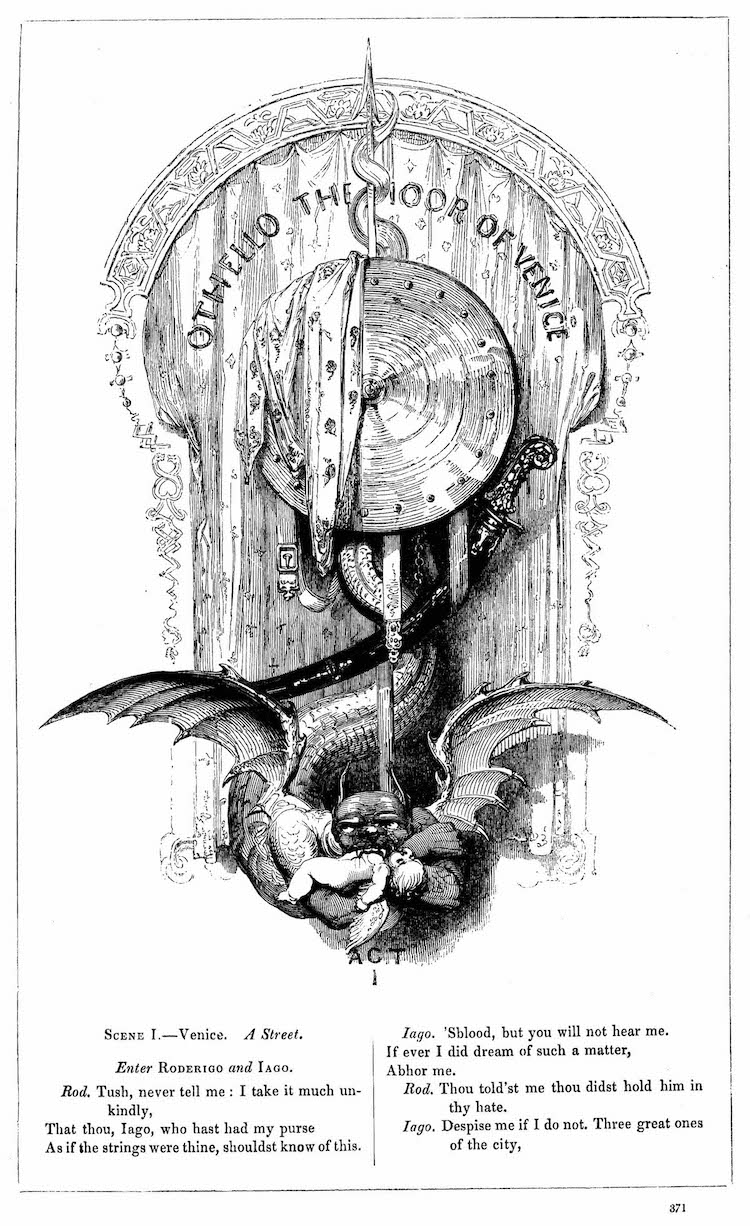

“Othello” Act I Header. The Works of Shakspere /Illustrated with Engravings on Wood, From Designs by Kenny Meadows. Published 1846.

How long did it take you to gather the material?

In this period thousands of editions and illustrations were made of Shakespeare’s plays so it was a relief to learn, after some research, that there were four major illustrated editions in this period: the one edited by Charles Knight (with different illustrators) and the ones illustrated by Kenny Meadows, John Gilbert, and H.C Selous. The archive consists of these Shakespeare editions and contains around 3,200 illustrations.

It did not take long to gather the material. None of it is particularly rare, as they were hugely popular in the Victorian period. For the sake of copyright issues and intellectual property, I bought these editions over a period of time for myself from old bookshops and on eBay. What is rare, however, is to find all these editions in one place at the same time. I suggest that the art of a digital archive is the art juxtaposition and creating a framework where these exciting juxtapositions can place to reveal to us new connections and relationships between illustrations, images, and texts.

What I find particularly compelling about the archive is when we look at a single scene that has been interpreted by each of the illustrators. What we find, I suggest, is that the illustrators are in certain ways, almost like proto-film directors, and it is no coincidence that the illustrated Shakespeare edition dies at the exact moment early cinema begins to take its hold on popular culture.

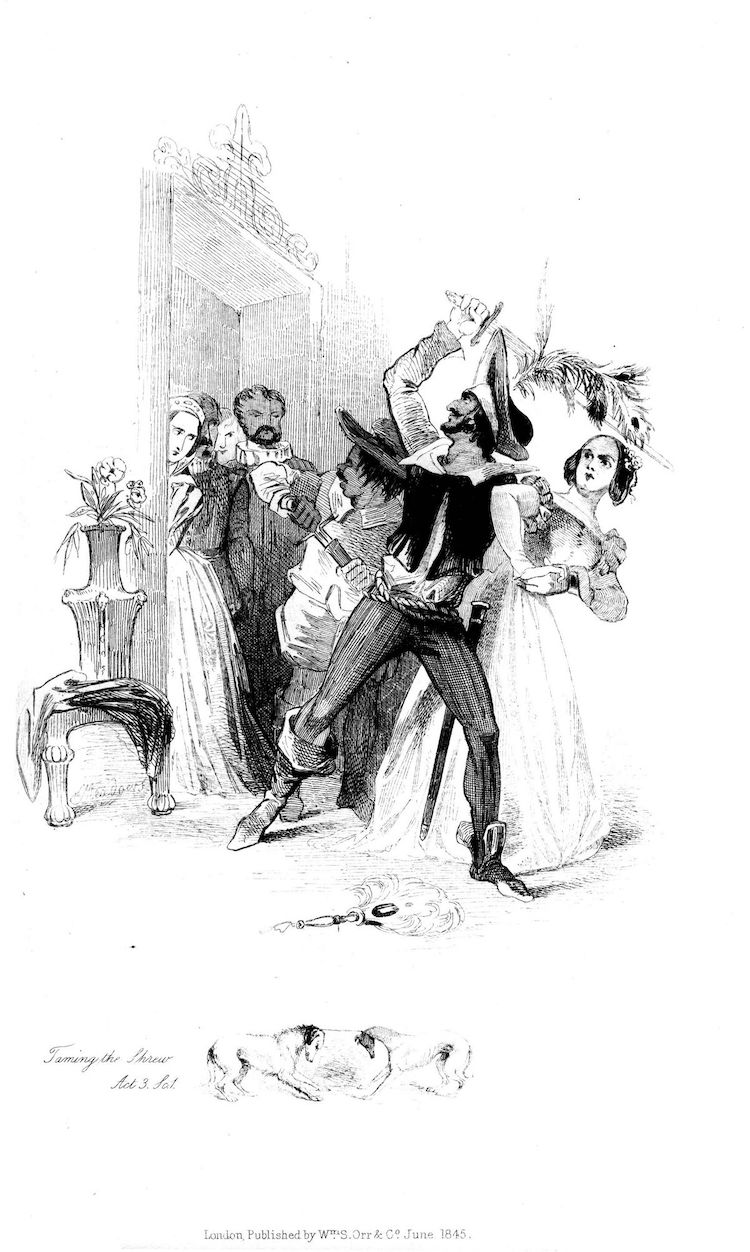

“The Taming of the Shrew” introduction. The Works of Shakspere / Illustrated with Engravings on Wood, from Designs by Kenny Meadows. Published 1846.

[continued] The decisions that the illustrators would face, and have to make, are those similar to a film director: how best to depict this scene in order to communicate meaning to an audience. What marks Shakespeare Illustration out (in contrast to, say Shakespeare, painting) is that like film, the events of the play are depicted sequentially. Whereas a painting will depict a single scene from a play, the illustrated plays are in a series. They pictorially, taken as a whole—like frames from a film—tell a narrative. This is significant, I feel, for our understanding of film history (as well as the Victorian period, book history etc). Illustrated books and their illustrators are often neglected critically, but I would argue that their work can certainly be seen as being a forerunner to emerging medium of cinema.

The process from scanning in the plays to what you see on the screen is a lengthy one. When a play has been scanned in I then use Photoshop to ‘clean up’ each illustration. This has all been done single-handedly by me for each illustration – over 3000 of them! Basically, everything you see in the archive has been done by hand and this is why it takes so long to get everything organized in a way that I’m happy with.

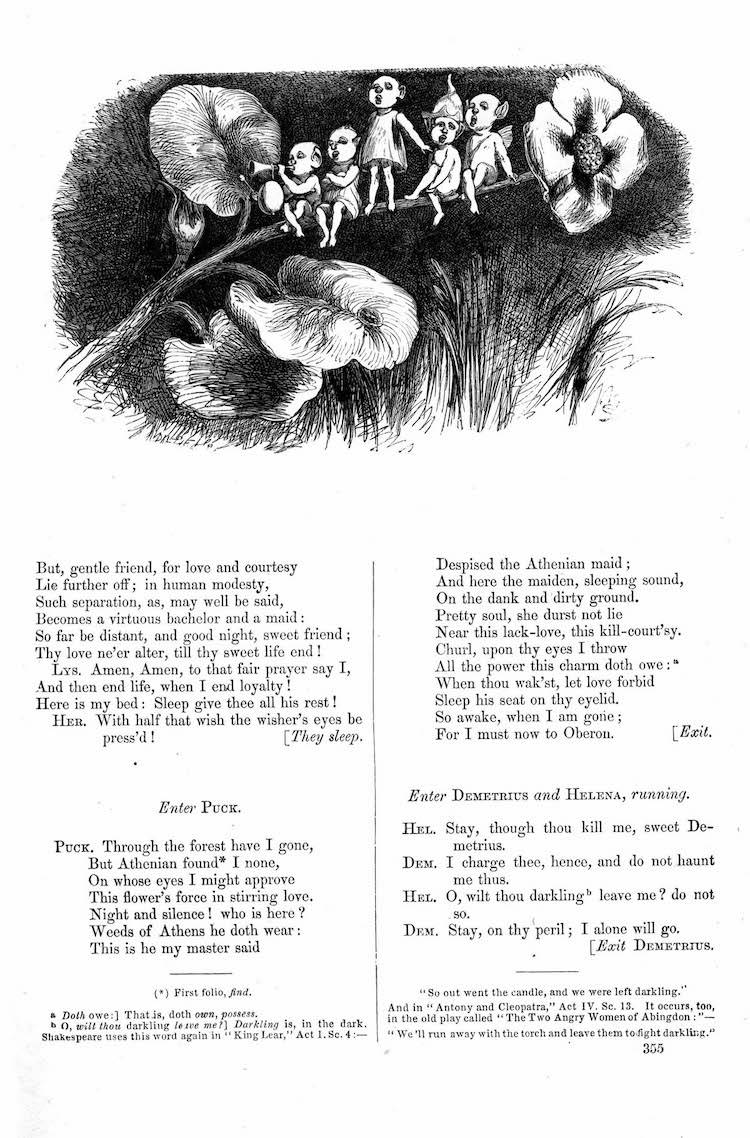

“Fairies’ Song” from A Midsummer Night’s Dream.The Works of Shakespeare / Edited by Howard Staunton / The Illustrations by John Gilbert. Published 1865.

Why was it important for you to make the material available online?

Making this material accessible in a user-friendly way was hugely important to me. These editions, which were very popular in the Victorian era, are an important, though forgotten, part of our cultural heritage. Importantly, these editions are only ever available to scholars in academic libraries.

My archive makes available online over 3000 of these illustrations and allows researchers and members of the public to explore a rich image archive and to ask new questions about this material: for example, how did the Victorians depict certain characters and plays pictorially? How does this portrayal differ throughout the Victorian era? Are particular characters or plays more illustrated than others? Does this signify the popularity or otherwise of these characters or plays? Are there pertinent gender, identity, or colonial implications in these representations?

“Imogen.” The Plays of William Shakespeare / Edited and Annotated by Charles and Mary Cowden Clarke / Illustrated by H. C. Selous. Published 1864–68.

[continued] Alongside such questions, the archive allows users to explore and interrogate the complex relationship that exists between the page and the stage and between word and image. Furthermore, the archive uses social networking to enable a community of users to discuss the images and to collaborate in exciting new and unforeseen ways. The archive has a Creative Commons license and I am very excited to see how people will use my work in the future, either for scholarly purposes or for ‘remixing’.

Underpinning the project is my strong belief that an online academic resource can be both scholarly rigorous and user-friendly. I felt quite frustrated with the insularity of much of academia and the complacency towards public engagement. By making this material online for all users I want to show to academics that their work can be ambitious, scholarly and popular and I wanted to demonstrate to the public that academic work can be massively exciting through bringing the past into the present.

“The Two Gentlemen of Verona” introduction. The Pictorial Edition of the Works of Shakspere / Edited by Charles Knight / Illustrated by William Harvey. Published 1839–42.

Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive: Website

My Modern Met granted permission to use photos by Michael John Goodman, The Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive.

Related Articles:

Shakespeare’s Famous Quotes on T-Shirts

Historical Figures Transformed Into Modern Illustrations

2,000 Suspended Steel Stars Installation Pays Dazzling Tribute to Shakespeare