This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

Lithuanian photographer Roza Vulf specializes in candid photographs rich with cinematic character. Now based in Rome, Vulf is a self-taught photographer who has spent the last seven years focusing on her craft.

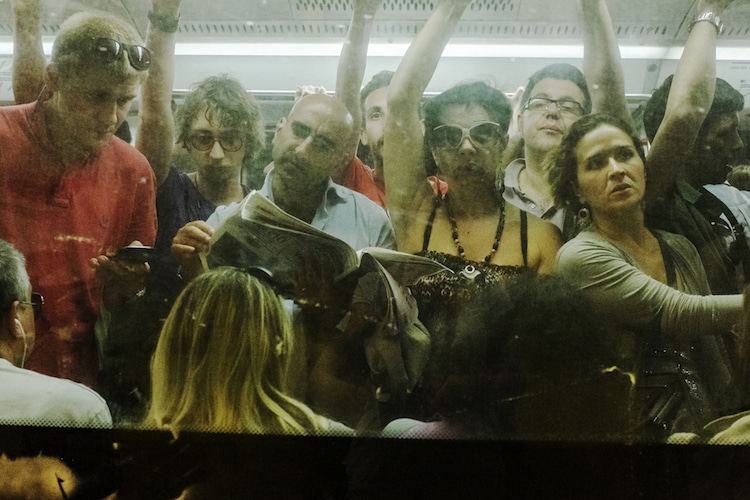

Her color street photography plays with light, color, and composition to weave a narrative inside each image. Her cunning ability to capture a moment allows viewers to insert themselves into the situation, searching like a detective for the full story.

We had a chance to speak with Vulf about her work, what made her turn to photography, and how she uses her anonymity and personal experiences to draw out the art in her photography. Read our exclusive interview below.

Can you tell us about your background in photography?

Can you tell us about your background in photography?

I have always had a tight connection with photography since I was a teenager. I remember I even had an internship with some local newspapers in Vilnius during the Soviet times. Back then, of course, I was shooting on film, using Russian cameras like “Smena” and “Zenit.” But life takes its own turn—I got married, had two kids, and had to get a reliable source of income, as well as study. There simply was no time to shoot professionally, so I was taking pictures of my children, family, and friends and developing them myself.

As time passed by, I changed to digital and kept documenting my travels and family life. Until seven years ago, when I moved to Rome and finally got the opportunity to dedicate most of my time to photography.

Being self-taught I relied a lot on books, magazines, and the web to help me develop my skills, as well as practice. I got subscriptions to some photography magazines and educational literature to follow lessons on landscape, macro, and everything else I found useful. I also attended a couple of workshops and always used the possibility to photo walk with photographers, which usually brings interesting experiences.

Have you always gravitated toward candid photography or is this something that developed over time?

Have you always gravitated toward candid photography or is this something that developed over time?

Shooting candid on the street has always been an instinctive choice since the very beginning. During years of relentless practice, I am mastering “the miracle”—as I call it—of candid photography in the realm of my own vision.

Capturing real scenes from real life has become second nature to me by now, and the idea of recreating a posed scene seems fake and obsolete in relation to my current work. But then again, I might explore this technique one day.

You talk about enjoying your anonymity as a street photographer. Often, cameras can act as a bit of armor in public, making us braver or helping us discover new areas. Do you find that’s the case with you?

You talk about enjoying your anonymity as a street photographer. Often, cameras can act as a bit of armor in public, making us braver or helping us discover new areas. Do you find that’s the case with you?

In my line of work, anonymity is principal. As an anonymous photographer on “set,” I ought to experience the freedom of my personal, as well as photographic, expressions.

Rather than being defensive, I prefer to blend with the environment and become relative and susceptible to the surroundings while photographing on the streets. It is only when I walk with my guard down I can seize the momentum of the immediate emotional connection with someone’s story. My camera becomes a natural mechanical extension of my mind instead of being an armor. Just a daring tool rather, that lets me capture those particular moments from the myriad of tales out there on the streets.

How do you think your images of strangers reflect what is happening in your own life?

How do you think your images of strangers reflect what is happening in your own life?

There is no way to escape our own emotional presence while we are in a creative process. Every single photograph I take contains a piece of me. To an extent, my entire body of work is made of my attitude, priorities, interests and the environment I am in.

I don’t think I would be original in saying that a lot of expressive work out there is often done by an artist in a critical mood. When we feel down or euphorically happy our sensitivity reaches extreme levels, making us see more, or sometimes notice less, than usual in situations and in people around us. This transformed into images becomes an extremely personal expression.

What’s one of the more memorable scenes that you’ve captured?

What’s one of the more memorable scenes that you’ve captured?

I have shot in many different countries and within various scenarios, the magnitude of which is not necessarily comparable to the extent of those of my contemporaries. But there are some shots that hold a sentimental value and a personal meaning being connected to or running parallel with certain events in my personal life.

One of them is a shot of a woman on the train in Israel. I was in a train carriage on my way home after having spent the day in a hospital with my ill father, trying to help him in his desperate and ultimate fight. I was deep in thought when in the darkness of the carriage I noticed a woman’s face in a ray of light and her pristine ghostly reflection in the window. I saw me.

Her expression was mirroring my emotional state with exact eerie precision. The composition of the entire scene suddenly visualized what I felt deep inside. For a second I noticed the unbearable sadness was in her face—just tiredness and frustration with no hope. Where the light has formed a divine-like radiance as if to reflect a tender intention.

What do you hope people take away from your photos?

What do you hope people take away from your photos?

I rely on my work’s ability to provoke a viewer’s mind, which can be both personal or objective.

And I hope the viewer can feel my love for the subjects in my shots, because I love humans in general. Even though there are probably more lonely or sad people in my work, but that is just because I can sense loneliness. Being older helps identify these emotional states.

Your images have a cinematic quality, is this purposeful?

Your images have a cinematic quality, is this purposeful?

Not deliberately, no. By now it has become a naturally occurring criterion of my work.

In spite of books being the main resource of pastime, cinematography has played a very special role in the growth of my creative perception and the way I understand the world.

Early films by Woody Allen, Antonioni, Jacque Deray, Tarkovski or Wim Wenders are great few examples of brilliant cinema, a symbiosis between visual and intellectual, which has left an impact on me.

What equipment do you use?

What equipment do you use?

For a year I have been using Leica M240 with a 35mm lens. I am not a big fan of wider angle lenses because I don’t like the distortion they usually introduce to the frame. For my street work a 35mm (and perhaps 50mm in the future) lens results in a more natural realistic perspective.

Before Leica, for several years, I used Fuji X100S with a 23mm fixed lens which is an equivalent of 35mm.

You’re Lithuanian, but currently living in Rome. Do you think living outside your native country helps in your ability to observe your environment?

You’re Lithuanian, but currently living in Rome. Do you think living outside your native country helps in your ability to observe your environment?

My entire life experience, with a will to keep an open mind, has forced me into a permanent mode of observation, trying to understand or interpret my surroundings.

Of course, being outside my natural habitat makes me notice things, makes me more aware. The level of curiosity towards a new culture or environment rises, and I find myself again on the street taking pictures of strangers in their natural environment.

Any projects you’d like to share?

Any projects you’d like to share?

There are a few recurring themes in my work. One of which is the “city’s underground.”

I have been working on the Under: Rome project for a few years now, which I connect to greatly. In the beginning, it was just a few trial shots which are now building up to be the entire series of photographic stories.

To me, an underground is an important and prominent place where thoughts and expressions are condensed in a space and air tight environment. It is a place where the regular and trivial reality of everyday commuting transforms into a universe. A surreal universe where limited physical space available forces us to be closer.

Perhaps one day I will turn this series, and the rest of my work, into a book.

Roza Vulf: Website | Instagram

My Modern Met granted permission to use images by Roza Vulf.

Related Articles:

Interview: Photographer Spends 6 Years Documenting Village Life in Eastern Turkey

Interview: Cinematic Photos Capture the Traditional and Modern Essence of Tokyo

Interview: Photographer Captures the Vibrant Pulse of 1970’s Disco in New York

Interview: Photographer Travels to Remote Areas to Document Disappearing Traditions