‘4 Colour Sun Wheel’

His is the story of a road less traveled, of an artist who only found his voice and discovered his calling later in life. For British land artist Richard Shilling, the road toward becoming a well-known exponent of this ephemeral art form was unexpected and winding. It began under the inspiration of fellow Brit Andy Goldsworthy, one of the leaders of the field, and has now led Shilling to teaching others to follow in his footsteps and find their own inner artists.

From playing with the transparency of color leaves to stacking rock totems, Shilling’s work is born from the environment and lives in the carefully studied photographs he takes of each installation. His initial studies after Goldsworthy’s work—a sort of personal, at-home art academy—have lead into the development of his own unique style, one that is now studied and admired by others.

We had a chance to chat with Shilling about his life and work, from his early beginnings discovering his own creativity to his new ventures aimed to teach children and adults how they, too, can discover their artistry.

Left: ‘Scarlet Oak Ball on Grass and on Leaves’ | Top Right: ‘Rowan Berries’ | Bottom Right: ‘Pebble Rubik’s Cube’

‘Dancing Totem’

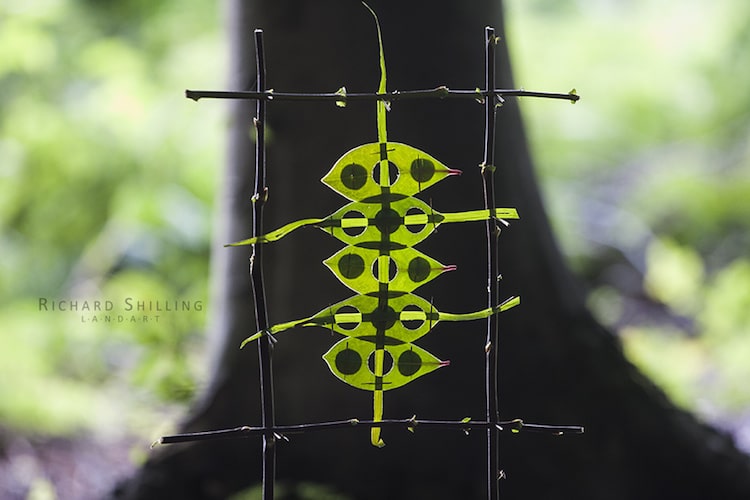

‘The Denizen of Antizen’

You’ve never had formal training, but would you say that art was something that intrigued you from an early age?

It is something I often reflect upon as I never expected or foresaw in any way that I would end up working as a professional artist. What you “think” you are and what path you “think” you are on go a long way towards defining your identity and until middle age, I never considered myself a creative person at all, it wasn’t what I thought I was and I never considered it a path that I should follow.

I always had an interest in art and in music. I played musical instruments, DJ’ed and enjoyed other peoples art but never thought that I had any talent for any of it. They were just fun things to do. I was never inspired or mentored by anyone, it simply was not something I was aware of that someone like me could be.

However, I was brought up in the countryside and during my childhood I spent most of my spare time exploring the woods and fields around my home, watching birds and wildlife. I was always (and still am) happiest when amongst nature and during my wanderings, I would rarely see anyone. For me that is the root of what I do now, my nature art is an expression of all that time I spent in natural settings absorbing all the cycles, endless variety, and abundance in nature that made me feel whole and in awe of everything around me. Nature art is simply just one way of expressing the joy of feeling at one with the environment.

‘Recede’

‘Geology Squares’

‘Thorax’

‘Melted Ice Imprint’

It’s well-known that Andy Goldsworthy was a big influence on your early work. How did you first come upon his work and what was it about his art that so moved you?

I was born and brought up in the South-East of England but eventually, I moved to North-West England for work and set up home in the city of Lancaster. As I explained I love the outdoors and one day I was out running in the local hills that overlook the city and on top of a remote moor several miles from the nearest road I came across one of Goldsworthy’s stone installations. Perhaps I had low blood sugar from the exercise! But I couldn’t quite get my head around what it was and why it was there. I asked around and eventually found out who had created it. I hadn’t heard of Goldsworthy at that time, but I bought one of his books and was instantly blown away by what I saw as I am sure many people who first see his work are.

It was his ephemeral sculptures that inspired me greatly. In a single moment, his vision communicated to me the potential of gathering together properties inherent in nature and combining them in such a way as to create a magical moment captured in a photograph. It was like hearing an electric guitar played beautifully for the first time. Before that moment the sound of an electric guitar did not exist in your world but afterward, you are forever changed by the discovery. And that is how it was with Goldsworthy’s work. Once I had seen it, my worldview and it’s potential instantly expanded and could not return to how it was before. That was the genius of his vision and his gift to me.

‘Autumn Chroma Wheel’

Left: ‘Pebble Fade 2′ | Right: ‘Rainbow Sun Wheel’

‘Equilibrium Stack’

You’ve since moved on from early homages to Goldsworthy to forging your own style. It can be so difficult for artists to understand their own style and what makes them unique. How was that creative process of discovery for you?

While I was studying his work I recreated a few of his sculptures in order to try and understand how they were made. Through doing so I discovered the real essence of ephemeral nature art and it was another unexpected revelation that only became apparent through the process of doing. For example, in order to make a sycamore box I found that it was necessary to find leaves with a perfect right-angled vein structure and by searching for those I discovered that not all leaves have them, many trees don’t have any at all and I needed to have a deep knowledge of the trees I was inspecting and the environment as a whole.

Goldsworthy’s vision was to find these inherent characteristics and then express them through his sculpture. I am often asked by students “how do I make this or that sculpture?” and that is also how I began. But that is missing the point of ephemeral nature art, you begin by exploring nature and its materials and then intuitively express them through what you create and not setting off with an idea of what you want to make and then making the materials comply to your pre-conceived design. It isn’t making things with nature, it is expressing nature through making things!

Once I realized this, it was like someone switched the lights on and it set me off on the path of peeling back the layers of nature and trying to see more deeply each time that I look. That is what it is all about and that epiphany was when I began to forge my own style which is an interconnected relationship of all the time I have spent during my life in nature and each new experience and what I find. It cannot be anything but your own work when you follow the creative process in an intuitive fashion.

At the time I was making a lot of things, taking pictures of them and posting them on Flickr for no reason but to keep a record of them for myself. However they started to get some attention and back then I didn’t consider myself an artist in any way, it was just a hobby and I took snaps just for my own pleasure. But with the attention came criticism about copying Goldsworthy’s work even though in my mind I was simply studying it as any student would and I didn’t realize that what I was doing would really be visible to anyone in the outside world and with not self-identifying as an artist I didn’t have the self-confidence to step out and forge my own way. Right at that time I received an email from an Italian land artist and teacher called Gabriele Meneguzzi and he said, “It is time for you to find your own style and express your own ideas, you have it within you!” And that helped me believe in myself for the first time and start to express my own ideas.

Left: ‘Robin Hood’s Bay Stack’ | Right: ‘Rhododendron Mandala’

‘Laurel Leaf Reflections’

‘Icicle Section Circle’

What is the most difficult—and most satisfying—part about using only objects found near you in the environment?

Funnily enough, the most difficult and most satisfying aspects are often the same things when I make something as those are where the deepest discoveries are made. The harder it is to complete something the more layers you can peel back in your experience of the environment. A lot of my leaves and light sculptures are very fragile and difficult to work with and degrade very quickly. Certain leaves will wilt and go brown within minutes and will not put up with any imprecise handling at all so the challenge of keeping a sculpture together long enough to take a photograph of it can be very challenging indeed.

It might take several hours to construct one and during that time the elements and atmospheric conditions will change. The wind normally picks up as a day progresses and by spending several hours constructing something then several more trying to photograph it in an optimum light you are imbued with a deep experience of those changes. You feel deeply what the wind is doing, what the clouds are doing, the moisture in the air, how the sun is moving as the earth rotates and so many more things. Without the process of creating something I just wouldn’t be connected as fundamentally to all those things and how nature is in constant flux. The more difficult it is the more deeply those things are revealed and the more frustrating but conversely satisfying the experience may be.

‘Chase the Setting Sun Wheel’

This might be better explained with a story:

A few years ago I made a sculpture called Chase the Setting Sun Wheel. The leaf colors I was finding reminded me of the colors and phases of the setting sun which I would often see living on the west coast of England hence the name. Once I had made the sculpture I attempted to take a photograph of it in perfect natural light, backlit to create the most contrast. I tried to do this for several hours and took a multitude of images but none of them were quite what I wanted. I became deeply aware of the movement of the clouds and the path of the sun as I spent those many hours trying to get the picture I wanted, it was both a difficult and frustrating experience whilst also being very meditative. But my efforts were in vain and I didn’t get the picture I wanted that day and went home disappointed. I couldn’t leave it at that and returned to the place I made it the next day, fixed leaves that had wilted and tried again for several more hours. In order to backlight it with natural light, I needed to wait late into the evening until the light was golden and at a low angle and then the final perfect moment arrived.

It often happens where there is a perfect moment where everything comes together and a sculpture lights up as if at its pinnacle moment and has come alive. And at that very moment as the sun lit it up like a firework a hoverfly flew up to it attracted by the color and the photograph was even better than I imagined it would be. Two days of toil, frustration and deeply connecting with nature resulting in a perfect moment. That’s really what it is all about and the description of ‘chasing the setting sun’ seemed perfectly apt.

That also describes the other most satisfying aspect of this art form. You use ephemeral materials and put all your focus and effort into creating something that reaches its zenith in only a short moment before beginning to degrade and returning back to nature from where it came. I absolutely love that. All that effort to see that magical moment before you simply just leave it behind. There is no way you can possess or own that moment beyond that time so you have to simply leave it and let it go and that is very liberating indeed and an allegory for the transience of our existence.

Read on to hear about Shilling’s most memorable installation and how he is helping adults and children discover their inner land artist.