Photo: PLOS Genetics

The Siberian permafrost is fertile ground for finding—and reviving—prehistoric life, from plants to animals to small microorganisms. A new article study in PLOS Genetics touches on something even more remarkable. In this case, not only were scientists able to find and revive 46,000-year-old roundworms, but they were also able to have them reproduce.

The prehistoric roundworms were previously unknown and have been dubbed Panagrolaimus kolymaensis by researchers. These incredible animals survived by entering a state known as cryptobiosis. Unfavorable environmental conditions provoke this extreme state of inactivity and cause the organisms to slow their metabolism so drastically that they, for all intents and purposes, appear dead. But organisms experiencing cryptobiosis aren’t dead at all and will return to normal once conditions improve. Think of it as hibernation taken to an extreme level.

In this case, once the female nematode was unthawed, she began to reproduce in a petri dish. It’s an incredible achievement that could have wide implications for our abilities to adapt and thrive despite adversity. It’s a lesson that is certainly valuable in an age when global temperatures are soaring.

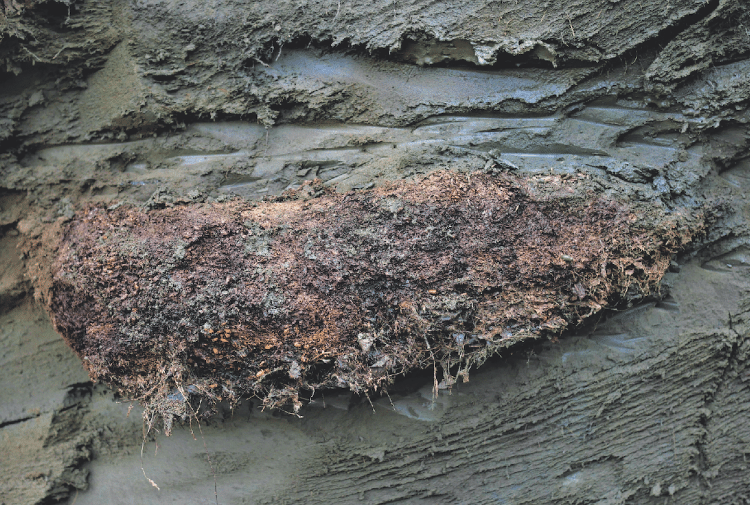

Permafrost deposit (Photo: PLOS Genetics)

“We need to know how species adapted to the extreme through evolution to maybe help species alive today and humans as well,” said Phillip Schiffer, a co-author of the study and evolutionary biologist at the University of Cologne in Germany.

While this isn’t the first dormant roundworm to be revived, the current example is far and away the oldest. Thanks to the radiocarbon dating of plant material surrounding the nematodes, scientists estimate these organisms are 46,000 years old.

The process of allowing a prehistoric organism to reawaken isn’t actually all that difficult. Scientists thaw the soil slowly so it doesn’t overheat the organisms. They then begin to move on their own, eat bacteria placed in a lab dish, and reproduce. And while the 46,000-year-old female that began reproducing is no longer alive, her offspring continue to thrive as scientists have cared for over 100 generations from the prehistoric roundworm.

h/t: [Smithsonian Magazine, Washington Post]

Related Articles:

Prehistoric 33-Foot-Long “Sea Dragon” Fossil Found in UK Reservoir

Researchers Examine Plants Brought Back to Life From 32,000-Year-Old Seeds

Biotech Company Raises $15 Million to Bring the Woolly Mammoth Back to Life

99-Million-Year-Old Baby Bird Feathers Study Sheds Light on Dinosaur Extinction