Known for their diverse yet distinctive styles and their subjective perceptions of the world around them, the Post-Impressionists pioneered a new approach to painting at the turn of the century. Unlike the Impressionists that preceded them and the Fauvists that followed, Post-Impressionist artists were not unified by a single aesthetic approach. Rather, what brought them together was a shared interest in openly exploring the mind of the artist.

Given the assortment of styles, techniques, and even subject matter evident in Post-Impressionist paintings, defining this art movement can be difficult. However, by tracing its history, identifying its artists, and pinpointing its distinguishing characteristics, one can begin to understand the historic and symbolic significance of the movement.

What is Post-Impressionism?

Vincent van Gogh, “The Starry Night,” 1889 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Post-Impressionism is an art movement that developed in the 1890s. It is characterized by a subjective approach to painting, as artists opted to evoke emotion rather than realism in their work. While their styles, therefore, wildly varied, paintings completed in the Post-Impressionist manner share some similar qualities. These include symbolic motifs, unnatural color, and painterly brushstrokes.

How Was Post-Impressionism Formed?

In the 1870s and 1880s, Impressionism dominated avant-garde art in France. Many up-and-coming artists, however, found fault in the Impressionists’ focus on style rather than subject matter. Aiming to shake up the contemporary art world, this group of stylistically dissimilar artists—including Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Georges Seurat, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, and Henri Rousseau—formed the Post-Impressionists.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, “At the Moulin Rouge,” 1892 (Jacob Wrestling with an Angel),” 1888 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Like Impressionist artists, the Post-Impressionists shared their work with the public through independent exhibitions across Paris. In 1910, noted art critic, historian, and curator Roger Fry coined the term “Post-Impressionism” with his show, Manet and the Post-Impressionists. Much like the Post-Impressionists themselves, Fry believed that the beauty of art is inherently rooted in perception.

“Art is an expression and stimulus to the imaginative life rather than a copy of actual life,” Fry explains in An Essay in Aesthetics. “Art appreciates emotion in and for itself. The artist, is the most constantly observant of his surroundings and the least affected by their intrinsic aesthetic value. As he contemplates a particular field of vision the aesthetically chaotic and accidental conjunction of forms and colours begin to crystallize into a harmony.” Today, these ideas help us to understand the common thread between these artists.

Post-Impressionism Characteristics

Emotional Symbolism

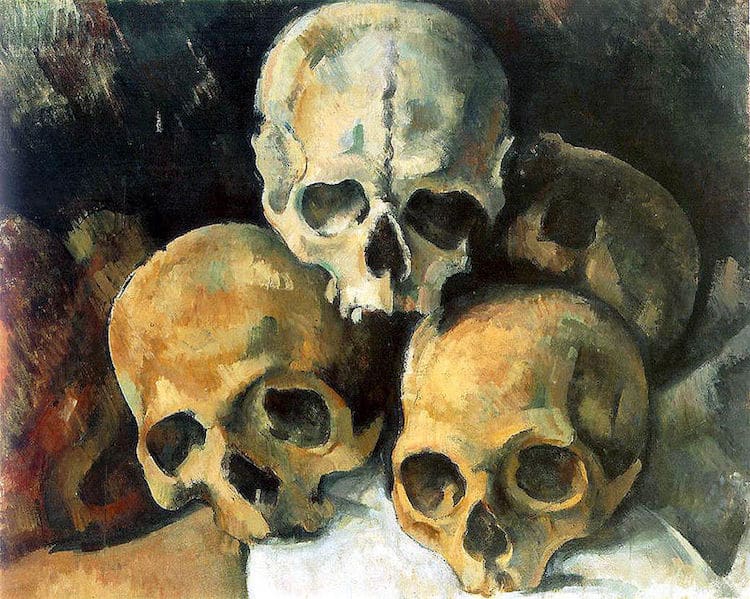

Paul Cézanne, “Pyramid of Skulls,” 1901 (Photo: Andreagrossmann via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

As Fry explained, Post-Impressionists believed that a work of art should not revolve around style, process, or aesthetic approach. Instead, it should place emphasis on symbolism, communicating messages from the artist’s own subconscious. Rather than employ subject matter as a visual tool or means to an end, Post-Impressionists perceived it as a way to convey feelings. According to Paul Cézanne, “a work of art which did not begin in emotion is not a work of art.”

Evocative Color

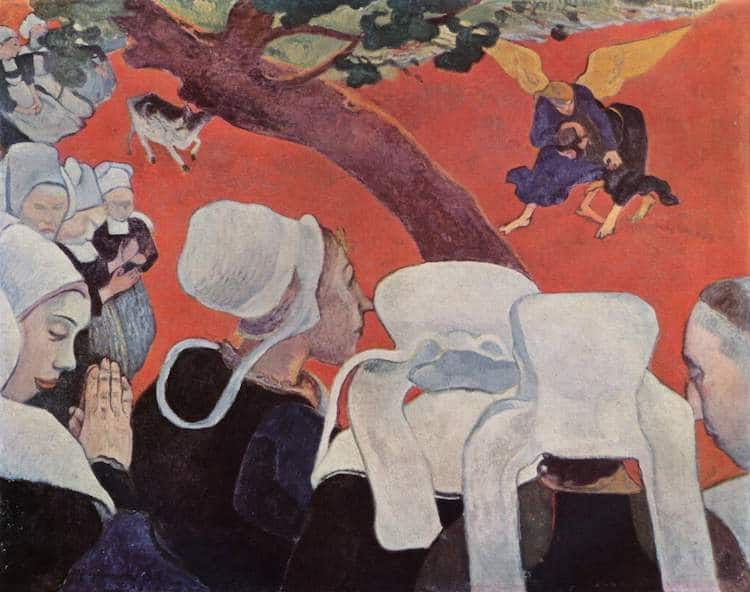

Paul Gauguin, “The Vision After the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling with an Angel),” 1888 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

“Color! What a deep and mysterious language, the language of dreams.” — Paul Gauguin

Unlike the Impressionists who strived to capture natural light’s effect on tonality, Post-Impressionists purposely employed an artificial color palette as a way to portray their emotion-driven perceptions of the world around them. Saturated hues, multicolored shadows, and rich ranges of color are evident in most Post-Impressionist paintings, proving the artists’ innovative and imaginative approach to representation.

Distinctive Brushstrokes

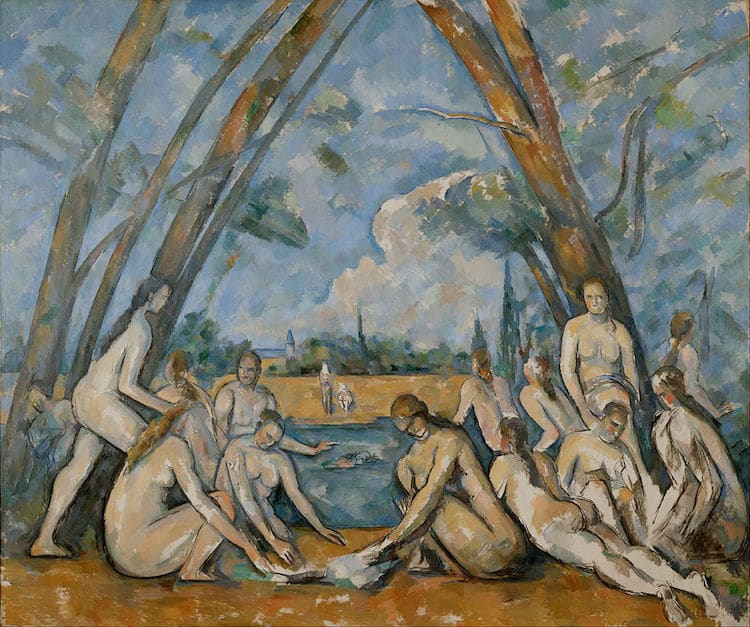

Paul Cézanne, “The Bathers,” 1898 – 1905 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Like works completed in the Impressionist style, most Post-Impressionist pieces feature discernible, broad brushstrokes. In addition to adding texture and a sense of depth to a work of art, these marks also point to the painterly qualities of the piece, making it clear that it is not intended to be a realistic representation of its subject.

Vincent van Gogh, “Undergrowth with Two Figures,” 1890 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Detail of “Undergrowth with Two Figures” (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Post-Impressionist Styles

Unlike many other major movements, a myriad of styles and sub-genres compose Post-Impressionism. These include Pointillism, Cloisonnism, Japonisme, and Primitivism.

Pointillism

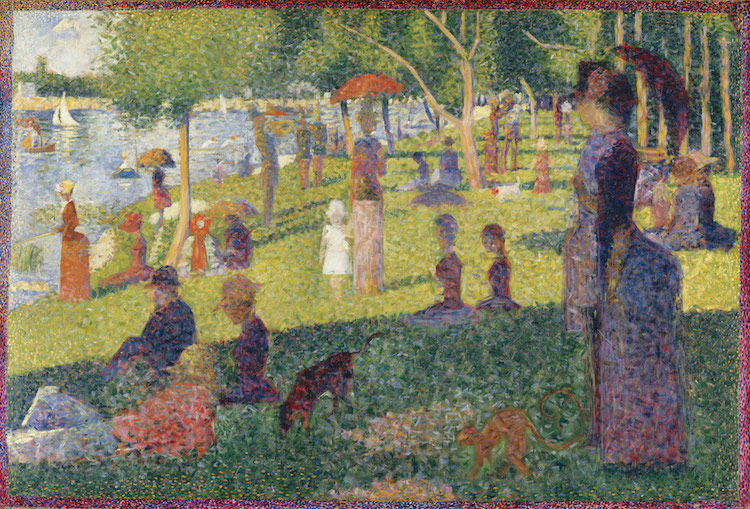

Georges Seurat, “A Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte,” 1884 – 1886 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Pioneered by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, Pointillism is a painting technique that employs small, colorful dots that work together to create a cohesive composition. Though inspired by the dappled brushstrokes of Impressionism, Pointillism depicts the focus on flatness and formality evident in many Post-Impressionist pieces. Seurat and Signac introduced the method in 1886 and continued working in this style throughout the entirety of their careers. Seurat’s painting A Sunday Afternoon the Island of La Grande Jatte is often regarded as a hallmark of this style.

Cloisonnism

Paul Gauguin, “The Yellow Christ,” 1891 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Cloisonnism is a Post-Impressionist style characterized by flat areas of color and dark linework. It was developed by two French artists Émile Bernard and Louis Anquetin, who modeled the style after Japanese woodblock prints (a highly popular collector’s item among artists of the time) and stained glass. Paul Gauguin joined later and produced some of the Cloisonnism’s best-known examples, including The Yellow Christ. Art critic Édouard Dujardin named the style after the decorative technique cloisonné, which describes metalwork objects that contain colorful glass within wireframes.

Japonisme

Vincent van Gogh, “Portrait Père Tanguy (Father Tanguy),” 1887 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Similar to the ways in which Impressionist artists found aesthetic inspiration in Japanese art’s use of perspective and treatment of color, Post-Impressionists—namely, Vincent van Gogh—emulated and even imitated ukiyo-e prints in their work. In some pieces, like Flowering Plum Tree (after Hiroshige) and The Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige), Van Gogh replicates well-known works of art. In others, like Portrait of Père Tanguy, he simply employs Japanese art as an accent.

Vincent van Gogh, “Flowering Plum Tree (after Hiroshige),” 1887 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Left: Vincent van Gogh, “The Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige),” 1887 (Photo: Google Arts & Culture via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Van Gogh admired Japanese art for the emotional impact and philosophical qualities of its content. “When we study Japanese art, we see a man who is no doubt wise, philosophical and intelligent. And how does he spend his time?” he asks in a letter to his brother, Theo van Gogh, in 1888.

“He studies a single blade of grass. But this blade of grass leads him the draw plants of all kinds, then the seasons, the overall aspects of the landscape, then animals, and finally, the human figure. This is how he spends his life, and life is too short to do the whole. Come now, isn’t it almost a true religion which these simple Japanese teach us, who live in nature as though they themselves were flowers? And it seems to me that we cannot study Japanese art without becoming much gayer and happier, and we must return to nature despite our education and our work in a world of conventions.”

Primitivism

Paul Gauguin, “Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going?” 1897 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Though a “primitive” aesthetic has been used by artists across many movements, it is most closely associated with two genres of art: Post-Impressionism and, later, Cubism.

Post-Impressionist artists like Paul Gauguin and Henri Rousseau pioneered the modern art approach with pieces like Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? and The Sleeping Gypsy, respectively. These pieces exhibit the two main qualities of Primitivism—an interest in non-Western subject matter and a naive style of painting—and also capture the artists’ interest in emotional and even dream-like subject matter.

Henri Rousseau, “The Sleeping Gypsy,” 1897 (Photo: Oakenchips via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Ultimately, though composed of many characteristics, styles, and even sub-genres, Post-Impressionism conveys the inherent connection between emotions and art, proving the power and potential of the artist’s mind.

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

Art History: How Van Gogh’s ‘The Starry Night’ Came to Be and Continues to Inspire Artists

10+ Awe-Inspiring Impressionist Masterpieces Painted by Claude Monet

20+ Brilliant Quotes About Art From Famous Artists and Great Creative Minds