Boy with a watch. Comacchio, Italy, 1955.

As a pioneer of Italian photojournalism, Piergiorgio Branzi captured a pivotal moment in European history—following the end of World War II. Starting with a motorcycle voyage down the Italian coast less than a decade after WWII and continuing with reportages in Spain and Moscow, his work blended documentary and fine art photography to great effect. Now 89 years old, he finds himself part of a legacy of early Italian photography that inspired generations to come.

Growing up in Florence, Branzi was not destined to become a photographer. In fact, he was working in his father’s bookstore and studying law when a chance encounter with an exhibition changed the course of his life. “In 1952, I was enrolled in university studying law when Henri Cartier-Bresson‘s first touring exhibition arrived in Florence,” Branzi tells My Modern Met. “I’d never been interested in photography, but it was like going to the movies for the first time. The photos were the essential nucleus of Cartier-Bresson’s work—India, the King of England’s funeral… I left the exhibit and bought a camera. I thought, this is a new language. In a certain sense, it’s like when the computer or cell phone was created. This new technology sparked a passion in me.”

Having also viewed some photographs of Tibet by famed ethnographer Fosco Maraini, Branzi was intrigued about the state of his own country, one that he’d never been able to travel due to the war. He was determined to mold the new language of photography into something truly his own, breaking down the barriers that often seemed to separate photographer and subject in the works he viewed. Instead, he took inspiration from Paul Strand and Marcel Duchamp, mixing his innate artistic sensibilities—he both paints and does etchings—with the technology of the time.

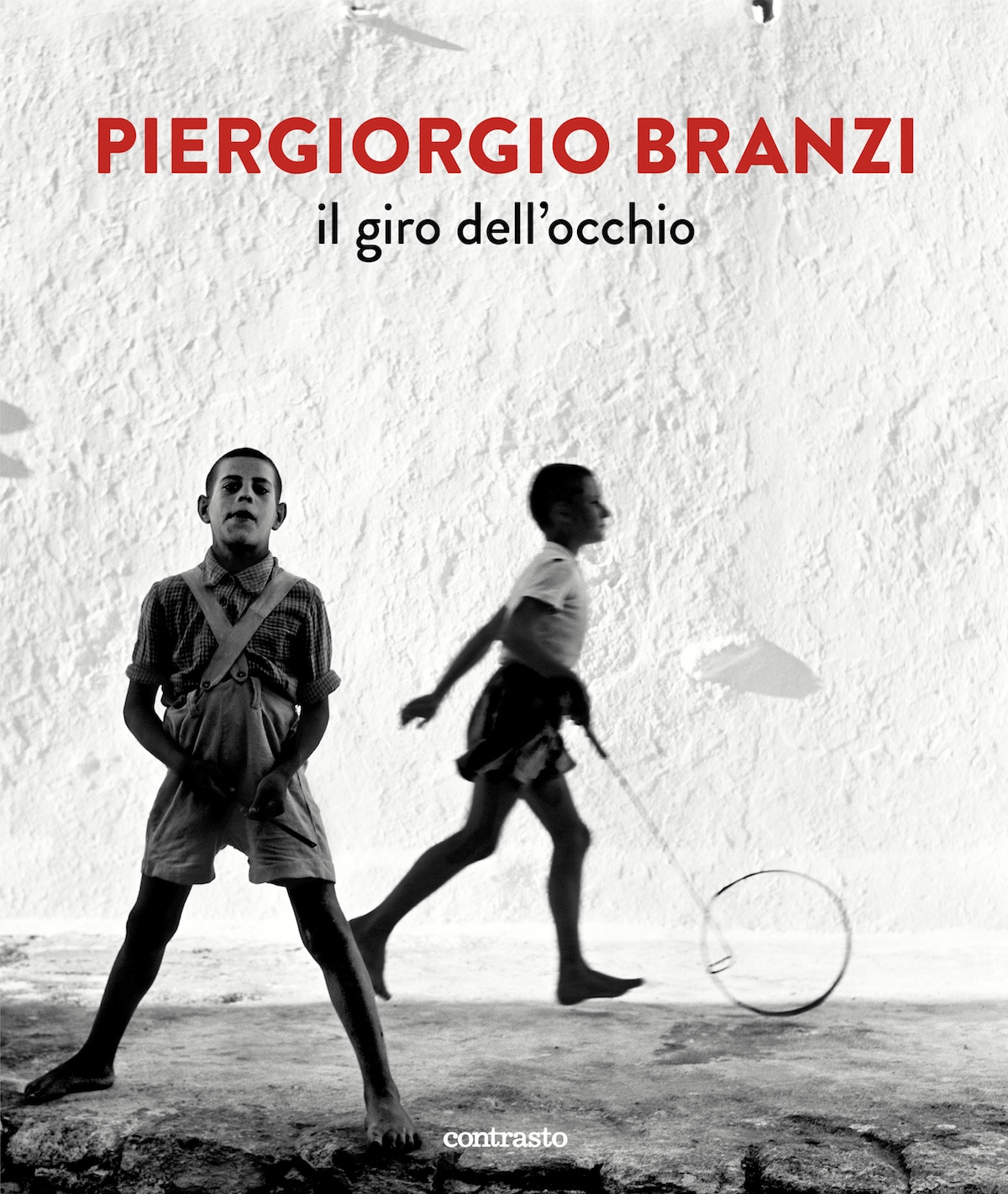

Mykonos, Greece, 1957.

In the mid-1950s, he convinced the brother of his girlfriend (now his wife), who was a motorcycle enthusiast, to travel with him around southern Italy on a Guzzi 500, to see how this once agrarian society had been transformed by World War II. This was followed by trips to Greece and Spain, where he was inspired by literature and the thought of a society that had been so similar to Italy, yet wasn’t drawn into war. What he brought back with him from those trips was groundbreaking work, which showed a society that so few had seen on film. They were images where Branzi tried to enter into society, becoming part of its fabric rather than keeping his distance.

In Italy, as opposed to France or the United States, photojournalism was still relatively new, and there were few outlets to publish his work. Yet, Branzi persevered and became widely known abroad. And later, he even met his original inspiration, Cartier-Bresson, after hopping a train to Paris and knocking on the doors of the Magnum offices. There, he was greeted by the master himself, who took the time to look at the young photographer’s work and give him encouragement and advice.

Branzi’s experience as a photographer would later bring him into the world of journalism, where he was sent to Moscow to open the Italian newsdesk for the national RAI television channel. While the photographer sporadically continued his photography in Moscow, he mainly turned his attention to television journalism, leaving his camera behind for over 30 years before starting up again in 2007. Now, he turns his attention to painting, using his artistic skills in a different manner, but leaving us with an incredible documentation of post-War Europe.

Piergiorgio Branzi is a pioneer of Italian photojournalism, and traveled across southern Italy and abroad to photograph post-war Europe.

Milan exhibition center, Montecatini pavilion, 1958.

Horseman from La Mancia, Spain, 1956.

Beachside bar in Senigallia, Italy, 1957.

Gym at Lomonosov Moscow State University (from the series, ‘Moscow: 1962 – 1966′)

Cranes in the new neighborhoods (from the series, ‘Moscow: 1962 – 1966′)

Gypsy Zamba in Sacromonte, Spain, 1956.

Il Giro dell’Occhio, published by Contrasto, is a comprehensive look at Piergiorgio Branzi’s photographic legacy.