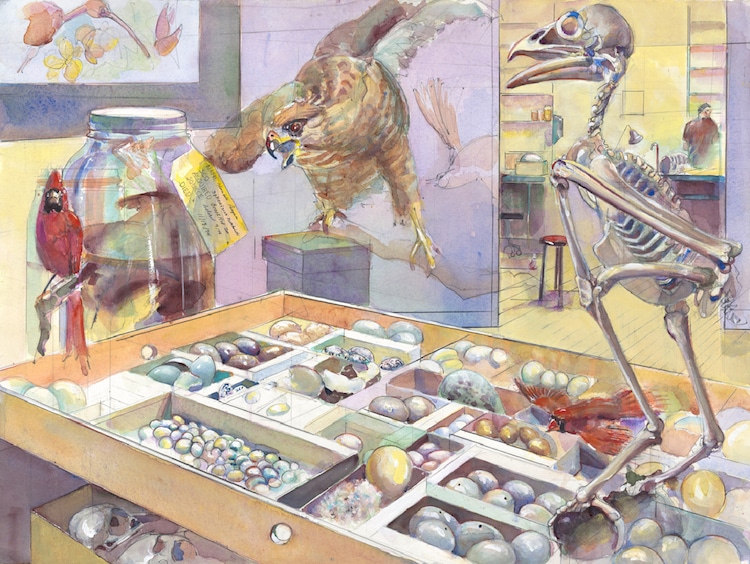

Painter Peggy Macnamara is no ordinary watercolorist. As the Chicago Field Museum‘s artist-in-residence, Macnamara’s muses include ancient vases, animal specimens, and other priceless artifacts that surround her on a daily basis. This fascinating career has led to an even more unique opportunity, as Macnamara’s art now aids in the crucial conservation efforts of the museum’s Keller Science Action Center.

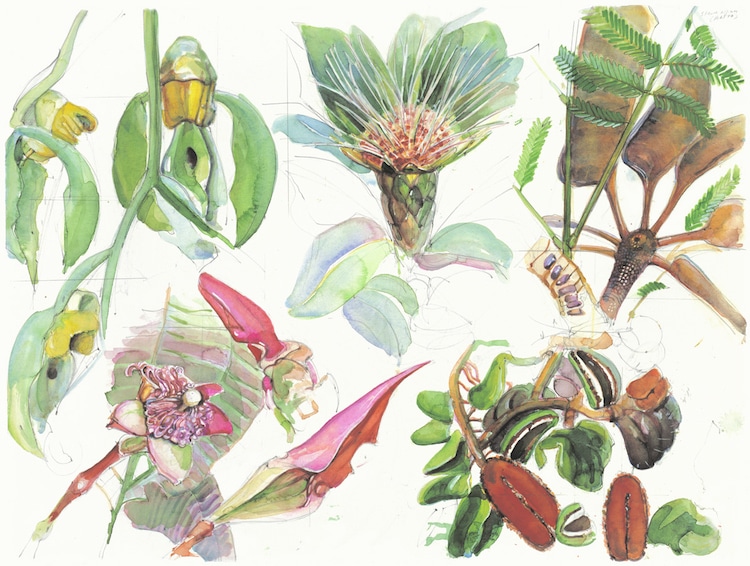

With their kaleidoscopic hues and loosely rendered lines, Macnamara’s whimsical watercolor paintings may not look like traditional naturalist studies; however, they have achieved exactly what the museum had hoped for. In addition to bringing attention to unique species of wildlife, they have helped the Action Center to make a case for Yaguas National Park, a preserve in the Peruvian Amazon supported by the institution.

For years, the Action Center has led efforts to protect the region, which has been described as “one of the most biodiverse places on Earth.” By capturing the beautiful flora and fauna found in this ecosystem, Macnamara has helped move this project forward with flying colors.

We recently had the chance to talk to Peggy Macnamara about her remarkable life and career. Read our exclusive interview below to learn more.

Your academic background is in art history. How has your area of study influenced your current practice?

Your academic background is in art history. How has your area of study influenced your current practice?

I majored in Art History in college because I didn’t believe I had the “talent” to be an artist myself. I went to University of Chicago for a Master’s under this false premise. It wasn’t until I began drawing on a regular basis in my mid-twenties that I began to see the true nature of talent. Now I reassure all my students that there is no lack of talent in each of us, just a lack of persistent work ethic. You have to unearth the talent, dig it out with consistent work. I did figure drawing a couple days a week and set up a studio in my attic to draw still life.

Before your residency at the Field Museum and after your graduate studies, you dedicated years to sketching objects in museums. What initially attracted you to the museum setting?

The Field Museum was about a 45-minute drive from my house. Parking was free at that time so I began going everyday. Teachers were admitted free and at that time I was teaching at a small college in Lake Forest. I planned to use the museum as a studio for the years my kids were small (I had five kids before age 30). The sitter would come and off I would go for four to five hours.

What inspired you to shift your attention from art and artifacts to animal specimens?

What inspired you to shift your attention from art and artifacts to animal specimens?

Once I drifted into the Bird exhibits on the first floor of the museum, sometime in my early thirties, I was hooked.

Have you always been passionate about wildlife?

Have you always been passionate about wildlife?

I wasn’t necessarily passionate about wildlife as a subject matter but what observing nature could teach me as an artist. I was drawing perfectly-made things. Each skeleton was a jewel of design. Every bird or bug was a surprise composition. This experience honed my sensibilities, helped me develop instincts for balance, beauty, as well as surprise.

How did you finally come into your role at the Field Museum?

How did you finally come into your role at the Field Museum?

In 1990, I was approached by Debby Moskovits, a scientist reviving the bird exhibits. She had watched me working over the years and asked if they could exhibit my paintings in the new bird exhibit. I was delighted and from that time on became known as the artist-in-residence. Later, they gave me a studio in the Bird Division, a floor above the public areas.

[continued] I began working on books at that time. First was a book about painting wildlife and then, Illinois insects, nests, migration etc. The books were a way to reach a broader audience. Debby Moskovits began the conservation department at the Field. Back in 2001, she asked me to do paintings of new species of plants found in an area of Peru they were trying to protect. That was the beginning of my contributing to the Conservation efforts.

[continued] I began working on books at that time. First was a book about painting wildlife and then, Illinois insects, nests, migration etc. The books were a way to reach a broader audience. Debby Moskovits began the conservation department at the Field. Back in 2001, she asked me to do paintings of new species of plants found in an area of Peru they were trying to protect. That was the beginning of my contributing to the Conservation efforts.

How did you develop your style?

How did you develop your style?

In the beginning, I was working in colored pencil, a very slow medium. I worked in the Chinese exhibit on the second floor of the Field Museum for about 10 years. All the work was colored pencil and the exhibits were quiet and easy to work in. This taught me much patience and how to layer colors. When I eventually moved into watercolor I had learned a great deal from slow observation and application.

[continued] I did spend a year or so outdoors to make the transition to watercolor. I never took a watercolor class, I just applied what I had learnt. My art history studies gave me a sense of what it took to become a draughtsman. Leonardo spent years in Verrocchio’s studio, as did other masters. They also studied those who had gone before by drawing sculpture, a practice I incorporated in my thirties. I just went every summer to the museums in Europe and the Met in New York. The list of museums I have drawn in is extensive. Please check out my site www.peggymacnamara.com, which shows some of this work.

[continued] I did spend a year or so outdoors to make the transition to watercolor. I never took a watercolor class, I just applied what I had learnt. My art history studies gave me a sense of what it took to become a draughtsman. Leonardo spent years in Verrocchio’s studio, as did other masters. They also studied those who had gone before by drawing sculpture, a practice I incorporated in my thirties. I just went every summer to the museums in Europe and the Met in New York. The list of museums I have drawn in is extensive. Please check out my site www.peggymacnamara.com, which shows some of this work.

See more of Peggy Macnamara’s wildlife watercolor studies below.

Peggy Macnamara: Website | Facebook

Peggy Macnamara: Website | Facebook

My Modern Met granted permission to use photos by Peggy Macnamara.

Related Articles:

Detailed Bird Illustrations on Feathers Promote Wildlife Conservation

Interview: Ceramicist Hand-Sculpts 100 Elephants in 24-Hour Livestream

Colorful Paintings Visualize the Energetic Souls of Wildlife