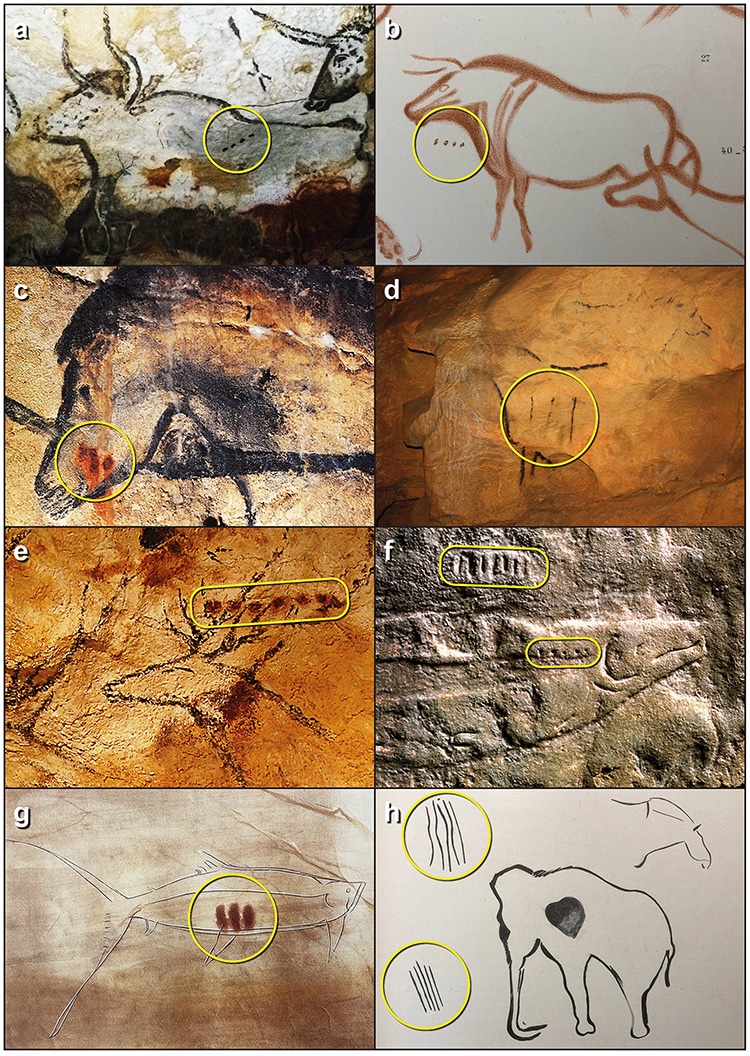

The meaningful proto-language dots on a cave painting from the Ice Age. (Photo: Bacon et al.)

Early humans, and our now extinct cousins, Neanderthals, have a long artistic history. Ancient cave art began as abstract shapes and handprints; but over thousands of years, it evolved into recognizable sketches of animals and plants. Many of the oldest cave paintings are in Spain and France. These scenes tell archeologists a lot about life in the late Ice Age, particularly about the hunting habits of early humans. However, certain repeated dots and lines found in animal cave paintings have mystified scholars for decades. Thanks to the clever deductions of a London furniture restorer, a recent paper in the Cambridge Archeological Journal announces these marks are in fact a proto-writing system and calendar which tracks each animals reproductive cycle.

For years, the mystery of the “random” lines and dots in cave paintings has remained unsolved. These markings appear across species of fish, reindeer, cattle, and other creatures daubed in ocher on cave walls around 20,000 years ago. Archeologists have long recognized the paintings’ importance to information sharing among early humans. “When wildlife biologists look at those paintings of reindeer and bison, they can tell you what time of year it was painted just from the appearance of the animals’ hides and skins,” Professor Brian Fagan told History.com in 2021. “The way these people knew their environment was absolutely incredible by our standards.”

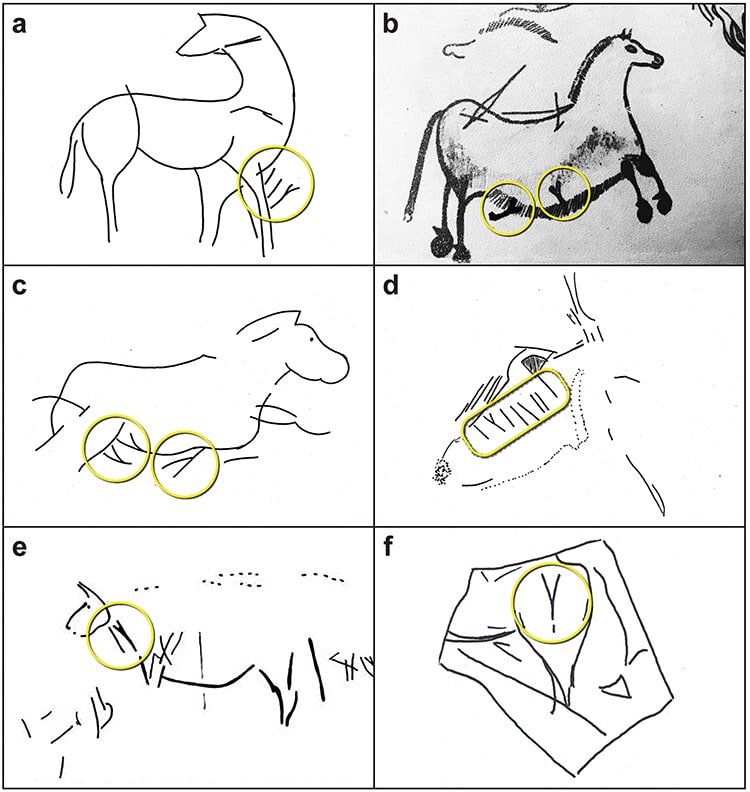

Ben Bacon—a furniture restorer and not an archeologist by training—set to work to crack the code of the dots and lines. He collected data from images of cave paintings on the internet and in the British Library. He says that he had “amassed as much data as possible and began looking for repeating patterns.” He was particularly curious about a Y-shaped sign, where a smaller line emerging from a main dash seemed to indicate to him the concept of “giving birth.” As he continued researching, Bacon came to the conclusion that the markings alluded to a lunar calendar.

He brought his hypothesis to academics at Durham University and University College London. Thankfully, they took his amateur conclusions seriously. They compared the markings to the birth cycles of similar modern animals, such as cows. This comparison showed that the Paleolithic markings likely refer to each creature’s mating season, marked in lunar months. Professor Paul Pettitt of Durham University explains, “The results show that Ice Age hunter-gatherers were the first to use a systemic calendar and marks to record information about major ecological events within that calendar.” While surprising, this is in keeping with researchers’ long-held conviction that cave paintings served an important survival function. It is an incredible example of a proto-writing system for a very cognizable purpose.

Professor Pettitt adds, “In turn, we’re able to show that these people, who left a legacy of spectacular art in the caves of Lascaux [in France] and Altamira [in Spain], also left a record of early timekeeping that would eventually become commonplace among our species.” Bacon, who is an author of the paper along with the formal scholars, mused how ancient humans are “a lot more like us than we had previously thought. These people, separated from us by many millennia, are suddenly a lot closer.”

Ben Bacon, a London furniture restorer, cracked a Paleolithic “code” in cave paintings of animals.

Animal cave drawings with sequences of dots. (Photo: Bacon et al.)

He collected data to deduce that the dots and lines actually track the reproductive cycles of the animals depicted in lunar months.

Ben Bacon, the London furniture conservator who cracked the Paleolithic code. (Photo: Durham University/PA)

The markings are a proto-language and calendar system which adds to the notion that cave paintings were important means of communicating knowledge in the Ice Age.

Examples of sign sequences with animal drawings. (Photo: Bacon et al.)

h/t: [BBC, Interesting Engineering]

Related Articles:

Metal Detectorist in the UK Finds a Medieval Diamond Wedding Ring

1,900-Year-Old Snacks Are Found in the Sewers Beneath the Colosseum