Self-portrait by Benjamin West, 1170 original, 1776 copy. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The American painter Benjamin West lived between two worlds. Born into the 13 American colonies in 1738, West immigrated to London as a young man to further his artistic career. He experienced the American Revolution as an expatriate in the mother country.

West’s birth across the pond, however, did not hamper his swift rise through the artistic ranks. Under the patronage of George III and English aristocrats, he rose to the level of President of the Royal Academy and Surveyor of the King’s Pictures—a Yankee truly making London his own.

Read on to learn more about West and his artistic career.

A Childhood in the American Colonies

The Benjamin West House in Pennsylvania, drawn in 1837. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Born in Springfield, Pennsylvania, West was the youngest of 10 children. Largely self-taught, young West showed promise at a very early age. By his late teens, he was taking portrait commissions around Pennsylvania. At 18, he completed his first historical painting, a genre that was esteemed and largely unknown in the American colonies. His wealthy patron, William Henry, had suggested the young man paint the ancient philosopher Socrates. Completed in 1756, The Death of Socrates was evidence of a revolutionary young painter.

The painting won him the attention of the Philadelphia intelligentsia. While living in the city, the young artist met John Wollaston, an English portraitist. He learned from Wollaston’s style and skill for painting fabric.

West’s wealthy city connections funded his continuing education by sending him abroad on a Grand Tour in 1760. The Grand Tour was traditional for young European noblemen and aspiring artists. While traveling, West spent three years learning in Rome, Florence, and Venice observing the art of the ancients and the Renaissance Old Masters. He would later draw upon these experiences as a pioneer of the art movement known as Neoclassicism.

Voyage to England

The West family, by an unknown engraver after 1779. (Photo: Yale University Art Gallery, Public domain)

In 1763, West traveled to London. There, his talent for history painting flourished. He quickly gained a glowing reputation in artistic and courtly circles. He hobnobbed with bishops and literary luminaries such as Dr. Samuel Johnson. He painted both Christian and classical scenes while supporting himself with portrait commissions.

It was an exciting time for art in London, as history painting was developing as a genre. King George III was also a devoted patron of the arts. In 1769, West delivered his first Royal commission, The Departure of Regulus.

“Mary Hopkinson,” by Benjamin West, circa 1764. This portrait was painted from a miniature during West’s early years in London. (Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Public domain)

King and artist proved to be a match made in artistic heaven. The Royal Academy was founded in 1768, and West would take over its presidency in 1792. After his first commission, West became the king’s preferred painter. He delivered 60 works to the monarch over the period between 1768 and 1801. Known as the “Historical Painter to the King” and later “Surveyor of the King’s Pictures,” he taught drawing lessons to the royal children and painted members of the family.

Historical Paintings

“Agrippina Landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicus,” by Benjamin West, 1768. (Photo: Yale University Art Gallery, Public domain)

It was during this period of royal patronage that West produced his most famous work entitled The Death of General Wolfe. Painted in 1770 and exhibited the next year, the painting depicts a battle in Quebec, Canada, during the French and Indian War. According to the National Gallery of Art, it is the “first major depiction of a contemporary event with figures in modern clothing,” as opposed to classical garb. The general is the central figure in the composition. He dies languidly, yet heroically, in his scarlet coat, illuminated as if from a light on high.

Not strictly factual, The Death of General Wolfe was meant to tell a moral story. Native Americans, lowly soldiers, and Canadian settlers were all supposed to appreciate the General’s bravery and sacrifice. Such idealized depictions of history were thought to be a “Hight Art,” nobler than other forms of painting.

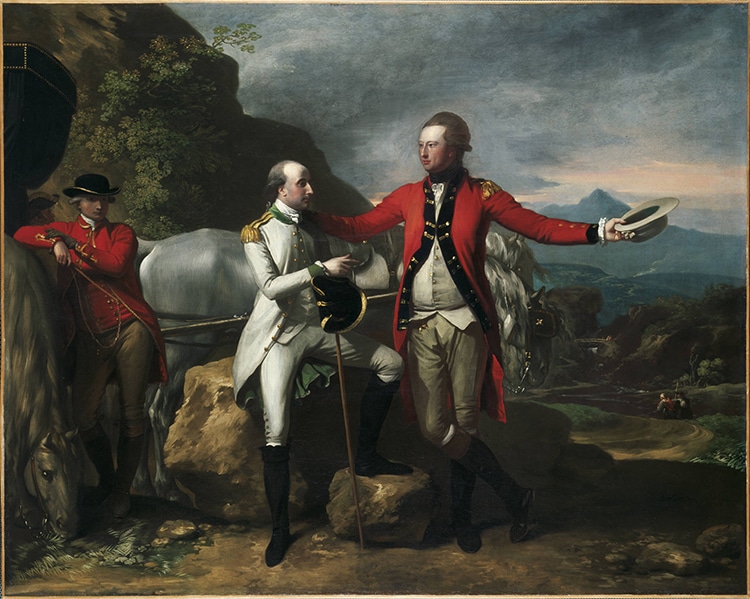

“Two Officers and a Groom in a Landscape,” by Benjamin West, 1777. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

History painting was a way to memorialize recent battles, but it could also evoke the classical past—albeit with some factual flexibility. These paintings also demonstrated ideal characteristics such as loyalty and bravery.

West’s 1768 work Agrippina Landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicus depicts the return of a bereaved widow to Rome to confront the emperor, suspected murderer of her husband. The central female figure embodies stoicism, self-sacrifice, and patriotism. Commissioned by the Archbishop of York, the neoclassical masterpiece also greatly appealed to the king.

“The Death of Nelson”, by Benjamin West, 1806. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Portrait Painter to Society

“Elizabeth, Countess of Effingham,” by Benjamin West, circa 1797. (Photo: National Gallery of Art, Public domain)

Known as the “American Raphael,” West was a leading light of London’s art scene. He trained generations of American artists who studied in London. These included John Trumbull, whose historical scenes of the American Revolution now hang in the U.S. Capitol and even adorn the U.S. $2 bill.

Despite his success as a historical painter to the king, West shifted to include more religious subjects in his maturing career. While the king’s patronage persisted through the American Revolution, West was eventually eclipsed as his sole favorite. The two maintained a close friendship, however. He continued to paint portraits for the English elite, and his sitters were elegantly posed in the midst of their noble pursuits. Attributes of classical architecture or historical painting appear in the background.

West had come a long way from painting Pennsylvania locals to the titled peers of England. However, he combined his past with his present in one of his later works. The portrait of his friend Benjamin Franklin shows the founding father flying a kite as he famously “discovers” electricity. A historical painting and portrait combined, it is emblematic of West’s storied career.

West passed away in London in 1820 at the age of 81. He left behind a rich legacy of paintings, pupils, and neoclassicism. As an American in London, West navigated a period of trans-Atlantic change both politically and artistically with style.

“American Commissioners of the Preliminary Peace Agreement with Great Britain,” by Benjamin West, 1783-1784. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Related Articles:

Who Is Camille Pissarro? Learn About This Pioneering Impressionist Painter

5 of Renoir’s Most Famous Paintings That Any Impressionism Lover Should Know

California Impressionism: How American Artists Adapted French ‘Plein Air’ Painting

9 Pioneering European Women Painters Making History in the 18th and 19th Centuries