Notre-Dame Chimera (Photo: Jose Ignacio Soto via Shutterstock)

Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris is celebrated as one of the most exquisite examples of Gothic architecture. Constructed in the Middle Ages, the church has welcomed worshippers and sightseers for centuries, inspiring awe with its sky-high spires, ethereal stained glass windows, and spell-binding sculptures.

Among carved depictions of holy figures like saints and prophets, the cathedral’s exterior also features a menagerie of grotesques, stone creatures intended to protect the church from malevolent spirits. When these statues double as waterspouts, they’re known as gargoyles—though the popular term is often mistakenly applied to the entire grotesque family.

The grotesques of Notre-Dame, for example, include both functioning gargoyles and a curious collection of decorative sculptures called chimera. While the latter do not drain water, they’ve come to be known as “gargoyles,” and are arguably the cathedral’s most famous feature.

Notre-Dame Cathedral (Photo: Alexandra Lande via Shutterstock)

The Original Gargoyles

Under Bishop Maurice de Sully, Notre-Dame’s construction started in the 1160s and lasted nearly 200 years. At the start of this endeavor, gargoyles were not a staple of French architecture. However, by the middle of the 13th century, the Gothic style was gaining popularity, with gargoyles at the forefront.

Inspired by age-old models found on temples in Egypt, Rome, and Greece, architects began adorning their designs with gargoyles in the Middle Ages. To reimagine this ancient concept, they looked to French folklore—namely, the 7th-century story of Saint Romain and La Gargouille, a fire-breathing monster whose head was nailed to a church to serve as a waterspout.

A statue of Saint Romain with Le Gargouille at his feet (Photo: Giogo via Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

As Gothic churches grew in size, so did their need for drainage systems. When paired with the increasingly superstitious nature of the contemporary Catholic church, this made gargoyles a perfect fit.

By the time Notre-Dame was finished in 1345, dozens of limestone gargoyles covered its exterior walls. Posing as both guardians and gutters, these creatures have a distinctive appearance, consisting of a hollow, streamlined body, a long neck, and an expressive, animal-like head. Often, they also have feathered wings, prominent, pointed ears, and clawed limbs tucked close to their body.

Gargoyles on Notre-Dame (Photo: Peter Cadogan via Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

Why this uniform appearance? According to art historian Michael Camille, the cathedral’s gargoyles look alike due to their ephemerality. “On medieval churches gargoyles rotted so quickly, if they did their job properly and carried off water, that only a century or so after they were made they had to be replaced,” Camille claims in The Gargoyles of Notre-Dame: Medievalism and the Monsters of Modernity. “Not enduring like the saints in stone carved around the doorways below but contingent creatures, often carved in cruder limestone that had a shorter life, proper gargoyles were eminently replaceable.”

Gargoyles on the side of Notre-Dame (Photo: Sharon Mollerus via Shutterstock)

This approach and consequent aesthetic contrasts that of the chimera, which are strikingly individual—and seemingly irreplaceable. However, unlike the gargoyles, these sculptures are not an original fixture of Notre-Dame. In fact, contrary to popular belief, they don’t even date back to the Middle Ages; they were sculpted in the 19th century.

The Famous Chimera

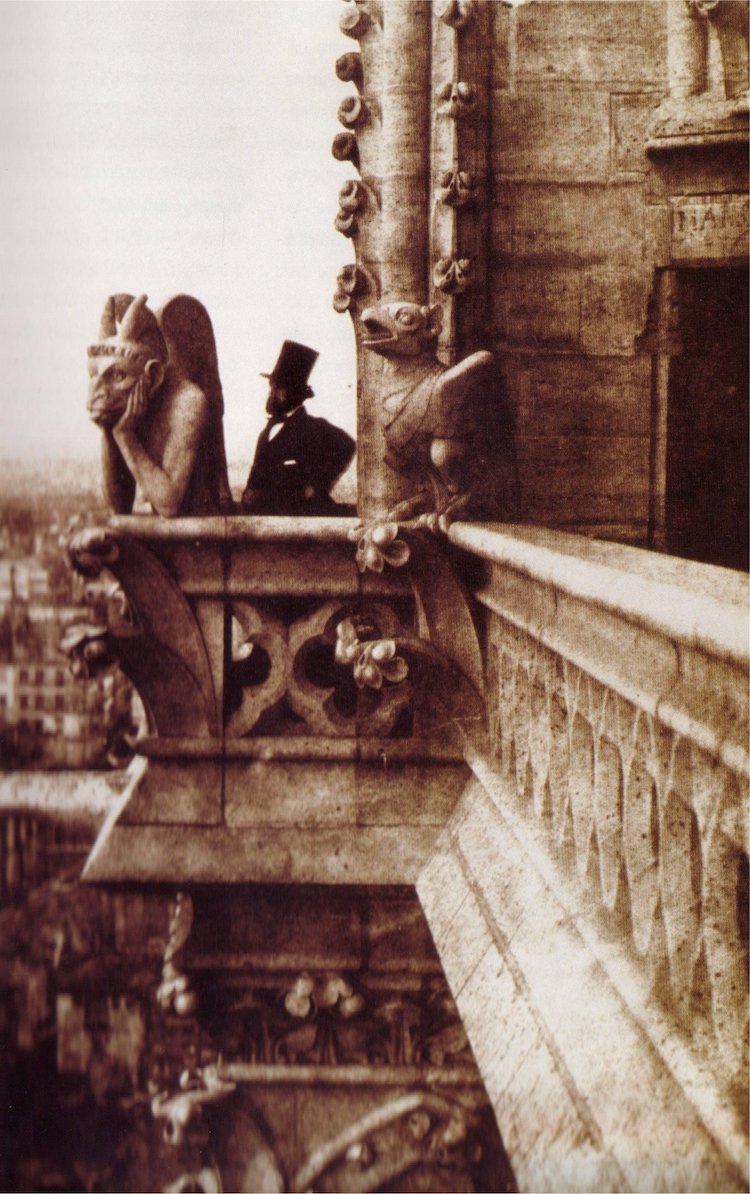

Charles Nègre, “Henri Le Secq near the ‘Stryge’ chimera,” 1853 (Photo via Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

In the 1800s, Notre-Dame was in crisis. Bored of the Gothic style and embracing Baroque architecture, Parisians all but petitioned for the crumbling cathedral’s demolition.

Fortunately, French writer, playwright, and preservationist Victor Hugo sought to save it. In order to remind the public of its historic importance, he penned The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, a novel that celebrates the mystery and magnificence of the Medieval cathedral. As a result of the book’s success, there was a renewed interest in the church, leading the king to call for its refurbishment.

In 1844, architects Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc were commissioned to restore the aging cathedral. The duo employed a team of craftspeople who repaired existing features and added new elements, including a 750-ton spire, copper statues, and the now-famous 56 chimera.

Unlike the gargoyles, these statues do not protrude from the external walls. Instead, they line the Galerie des Chimères, a balcony that connects the two bell towers. From here, they peer over the balustrade, where they eerily keep watch over the city and adorn the cathedral with their one-of-a-kind silhouettes.

Notre-Dame’s collection of chimera includes frightening animals, fantastical hybrids, and mythical creatures. Due to their unique personas, two of the sculptures have adopted nicknames throughout the years: Wyvern, a two-legged winged dragon, and Stryga (also playfully known as “the Spitting Gargoyle”), a horned creature with his head in his hands and his tongue sticking out.

Wyvern (Photo: starryvoyage via Shutterstock)

Stryga (Photo: Savvapanf Photo via Shutterstock)

Other famous—albeit nameless—characters include a one-horned demon, a goat-human hybrid, a plucky heron, and a not-so-scary elephant.

The Grotesques Today

Today, visitors to Notre-Dame Cathedral can spot both the looming gargoyles and the perched chimera. For a better view of both genres of grotesques, curious guests can even ascend the towers and walk across the Galerie des Chimères. While this climb comprises 387 steps up two sets of spiral staircases, it will undoubtedly be worth it when you’re face-to-face with its famous dwellers.

Up close and personal with the chimera (Photo: S.Borisov via Shutterstock)

Related Articles:

16th Century Gothic Boxwood Miniatures With Extremely Detailed Carvings

How Marble Sculptures Have Inspired Artists and Captivated Audiences for Millenia

These Drawings of Europe’s Most Beautiful Churches Are Tiny But Packed With Details