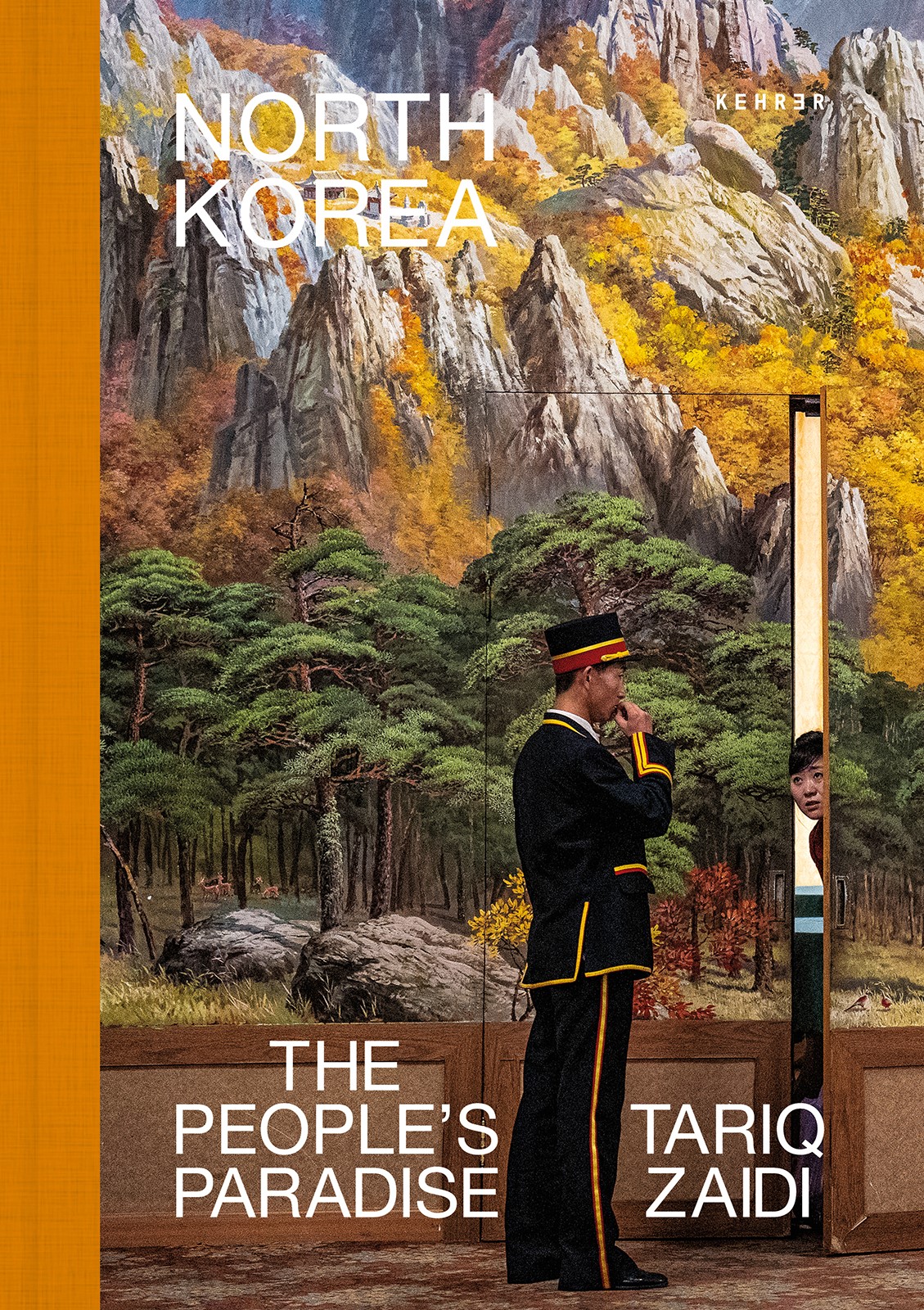

Photo: ©️ Tariq Zaidi

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

To most of the world, North Korea remains a mystery. And much of what we do know about the country is tied up in politics. That is why the few glimpses we get of life in North Korea are so important. They help humanize an often misunderstood culture, even if what we see is tightly regulated.

When photographer Tariq Zaidi took his first trip to North Korea in 2017, he was one of just 5,000 non-Chinese tourists allowed to enter the country that year. Led along a carefully choreographed itinerary in the company of two North Korean handlers, Zaidi was given a carefully curated glimpse of the country. While this didn’t allow for spontaneous moments, it certainly gave Zaidi the opportunity to see many different aspects of North Korea.

In his new book, North Korea: The People’s Paradise, he’s sharing his images with the world and, in doing so, helping us gain rare insight into a world most of us will never see for ourselves. We had the opportunity to speak with Zaidi about his time in North Korea and get his thoughts on his unique experience. Read on for My Modern Met’s exclusive interview and keep up with Zaidi’s work on Instagram, Facebook, and his website.

Photo: ©️ Tariq Zaidi

What first inspired you to travel to North Korea?

On my first trip in 2017, my original plan was to dive into the vibrant atmosphere of the annual beer festival, an event where foreigners and locals mingle “freely” and capture moments through the lens of a camera without hesitation. But fate had other plans that year—the beer festival was indefinitely postponed, leaving me with a tightly guided tour of the country. While it wasn’t what I had initially envisioned, the guided tour offered its own insights and surprises. With each step, I discovered hidden gems and cultural treasures that I might have overlooked in the bustling excitement of the festival. Though I missed the spontaneous interactions of the beer fest, I embraced the structured journey, immersing myself in the rich tapestry of the country’s history and traditions.

In my book, I use candid photography to explore the ordinary in this extraordinary state—everyday lives explored through a lens, illuminating the complex dynamics of people navigating their own paths within their country while the country does the same globally.

Inviting readers to delve beyond the headlines, North Korea: The People’s Paradise sheds light on people’s experiences and reveals the diverse tapestry of the country’s people and culture, challenging our preconceived notions about North Korea. Throughout this book, photography illustrates the hidden stories and realities that lie within its borders and the curtain of secrecy that dominates the narrative surrounding the country.

Photo: ©️ Tariq Zaidi

What surprised you the most about what you saw in the country?

North Korea reminded me of the DDR (East Germany with the Berlin Wall intact), Cuba, Vietnam, and China about 20 years ago. I’d say it’s a mix between these and some Central Asian countries I have visited in recent years, but more orderly and cleaner. It’s all relative, though—there were considerable differences in the rural versus urban contexts in North Korea in terms of aesthetics, people, and lifestyles.

From your perspective, how isolated is life in North Korea?

The only real links are to Mainland China and Russia. Visiting North Korea is a rare privilege afforded to only a few individuals globally. The country attracts around 5,000 non-Chinese tourists annually; those fortunate enough to visit are met with strict rules and regulations, including the control of photography.

Photo: ©️ Tariq Zaidi

Given the notorious restrictions placed on photographers who visit, were you worried about what you would be able to photograph?

For the past four years, since January 2020, North Korea has been inaccessible to all visitors, including North Koreans residing outside the country. Before this closure, access (for most nationalities) was possible through various agencies in China or Russia, involving a process of applying for permission/visas. During my visits, I was always accompanied by two North Korean minders. This applies whether traveling alone or in a group. They regularly scrutinized my photographs and occasionally requested deletions. The places, routes, and destinations were all predetermined and could not be altered once set.

What was it like to work there?

North Korea had several logistical and physical restrictions, but I never felt unsafe, nor was I met with hostility. I’m pretty used to working in challenging or inflexible environments. Some projects I’ve worked on in the past have had significant safety restrictions because the subject has been dangerous, politically volatile, or violent; others have had transport and mobility limitations where getting around the country and visiting points of interest has been impossible simply because of lack of infrastructure. Rules are there regardless of where I work; it’s just the kind of restrictions that differ.

Photo: ©️ Tariq Zaidi

How did people in North Korea react to you photographing them?

Children were generally OK with me taking pictures, and adults allowed me to take photos after a few minutes of politely asking, although it did depend on where we were. In the metro, for instance, when I pointed my camera at people, they all shyly put their heads down to avoid being photographed. I’m unsure if that was due to cultural differences, shyness, or the lack of camera culture.

Like anywhere else in the world, I photographed those willing to be photographed and respected those who were not.

Photo: ©️ Tariq Zaidi

Is there any particular photo you took and were made to delete that you regret having to get rid of?

I had taken many pictures at an amusement park in Pyongyang at night, which were deleted. It was a very surreal environment to photograph, given the political situation in 2017, and I wish I had been allowed to keep those. The guides didn’t mind me taking photos of groups of people going about their daily lives, but individual portraits I had taken were deleted. It’s hard to say what else I could have photographed because of how curated my first trip was—I didn’t have the chance to explore on my own and find stories.

Photo: ©️ Tariq Zaidi

What was the most memorable part of your time in North Korea?

During my photography sessions, the North Korean guides played a crucial role in shaping the subjects I could capture through my camera lens. They primarily guided me on what issues were allowed and what was prohibited. At the end of each day, they evaluated the photos taken and advised which ones should be discarded, emphasizing the importance of retaining high-quality images. Their insistence on achieving “good photos” amused me, prompting me to pledge improvement in my photography.

The guides frequently requested to view my images, leading to the immediate deletion of those they deemed unacceptable, regardless of their relation to the military. In response to my query about why non-military images were discarded, they explained their focus was on capturing exceptional visuals, encouraging a pursuit of photographic excellence.

The NK guides significantly influenced the scope of my photography, prohibiting images related to the military, consistent with global norms. They also discouraged photographing individuals alone but allowed group shots. Photography involved rapid shifts between locations, allowing little time for shooting.

Many images were taken in motion, capturing street scenes from moving vehicles. Conversely, authorized locations like the Science Center and official monuments were photographed with guide accompaniment.

Photo: ©️ Tariq Zaidi

How did the book project come about, and how was the selection process for the images in the book?

As with most of my previous books, such as Sapeurs: Ladies and Gentlemen of the Congo and Sin Salida (No Way Out), my process begins with a developing interest in a subject. This curiosity prompts me to explore it further through research and reading, often followed by multiple trips to the location over several years. After each trip, I present my findings to various editors to identify areas that need further investigation or development.

Once I feel the work is complete, I collaborate with a designer to create a book dummy. This involves selecting and sequencing images, crafting a narrative, and ensuring the format is suitable for a book. The dummy is then presented to potential publishers.

The final stages involve working closely with both the designer and the publisher to finalize the selection and arrangement of images. This process includes numerous iterations and discussions about the final images for the book, the format they will be presented in, and their sequence in the book. For my North Korea book, I collaborated with designer Stuart Smith and publisher Kehrer Verlag, who also published my first book on the Sapeurs: Ladies and Gentlemen of the Congo.

Between photographing, editing, researching, and writing, the entire project took over three years to complete.

Photo: ©️ Tariq Zaidi

What do you hope that people take away from these photos?

Many of my photographic projects deal with underreported communities and places. North Korea has intrigued me for years because of how little we know about it—except from mainstream media. I wanted to use photography to offer a glimpse at everyday lives in North Korea, documenting people, and culture as far as possible, given the limitations and restrictions of photography within North Korea. Beyond the militarism, authoritarianism, and control that have become associated with the country, people are going about their lives. This book seeks to present their realities (culture as far as possible, given the limitations and restrictions of photography within North Korea) to the rest of the world.

Through my practice, I endeavored to document what I witnessed, was shown, heard, and felt to the best of my abilities throughout my time in North Korea. Given the limitations of operating in North Korea, my goal is to provide readers with a comprehensive and immersive experience. Forming one’s perspectives now falls upon those who engage with my work.

North Korea: The People’s Paradise by Tariq Zaidi is now available for purchase.