Through his personal and professional life, one thing has remained constant for artist Nick Turner—his connection with horses. The American artist has led an eclectic life, which brought him to pass his adolescence in France before returning Stateside to study art.

As an artist who cuts across mediums—his work includes photography, drawing, and painting—a through line is his incorporation of nature and fascination with the equestrian world. Recently, he traveled to Iceland—a country that has long fascinated him—with the arts organization Twyla, in order to work on a powerful new set of self-portraits incorporating horses.

The final works are a study in energy and return to man’s animalistic instincts. Turner’s nude body, entwined with the wild horses, speaks on multiple levels. Recalling Classical sculpture, his muscles stretch and bow as they strain to meld with the horses. We recently had a chance to speak to Turner about his work, his fascination with horses, and the different levels of meaning within the series.

Can you share with us how your connection to horses began?

Can you share with us how your connection to horses began?

I was homeschooled as a child and then moved to France to attend high school and begin university. Feeling like an observer for a large portion of my younger years, and not a participator in social activities and not part of any real social groups, I tended to spend a lot of time riding horses which, unlike a lot of social interactions in school, I felt very comfortable with.

I competed in Eventing for awhile before bringing them into my work as an artist. After painting, drawing, and photographing them, and traveling the world looking for ways to capture them, I began placing myself into photos with them. I wanted to not be just a man standing with horses, but one of the pack.

Historically I find it important also to look at philosophers like Thomas Hobbs, and ideas like social contract theory where man and animal are referenced as one and the same when rules and laws are taken away and not there to structure set rules for them.

What do you think it is about horses that allow humans to create such a deep bond with them?

What do you think it is about horses that allow humans to create such a deep bond with them?

Historically horses have enabled man to innovate and evolve much faster because of the ability to travel and transport each other and things. Being a fundamental necessity to human growth and life, humans naturally protected and valued horses for this specific asset they became.

Can you tell us a bit about your path to becoming an artist and how your bond with horses became so intertwined with your art?

Can you tell us a bit about your path to becoming an artist and how your bond with horses became so intertwined with your art?

Horses were a big part of my life growing up and competing. It was a natural thing for them to stay present in my life and work, even though I don’t still ride competitively anymore. I do think something horses give me is my mind usually becomes quiet when I riding or just around them.

There’s something very therapeutic about horses. I often have trouble not living in my head and thinking constantly, and nature and horses, specifically, really quiet my mind and I only think that’s a good thing to be fully present, even if it’s for a short time.

Speaking specifically about your series set in Iceland, it’s clear you have a love of this country. Of course, many people come to photograph Iceland’s environment, but your work comes from a different place. How does Iceland’s environment influence your work?

Speaking specifically about your series set in Iceland, it’s clear you have a love of this country. Of course, many people come to photograph Iceland’s environment, but your work comes from a different place. How does Iceland’s environment influence your work?

You are right, I am fascinated by Iceland for a few reasons. Of course, it’s an incredible place to photograph nature and landscapes, but I also find the history and culture of Iceland inspiring as well. The horse culture there and how hardy and tough these horses truly are.

I grew up with this unique education being homeschooled and traveling a lot as a child before ending up based in France for awhile, and I read a lot of adventure literature like Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island and The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe by C. S. Lewis, so I had this somewhat magical or fantasy views on traveling and nature since I was a kid. Iceland has a sense of familiarity to it, something magical and inspiring. Like dragons could be living behind the jagged cliffs as you drive past. I think that has been one of the attractions to Iceland, this feeling like I’m on an adventure living in one of the books I read as a child to some extent.

Iceland has a sense of familiarity to it, something magical and inspiring—like dragons could be living behind the jagged cliffs as you drive past. I think that has been one of the attractions to Iceland, this feeling like I’m on an adventure living in one of the books I read as a child to some extent.

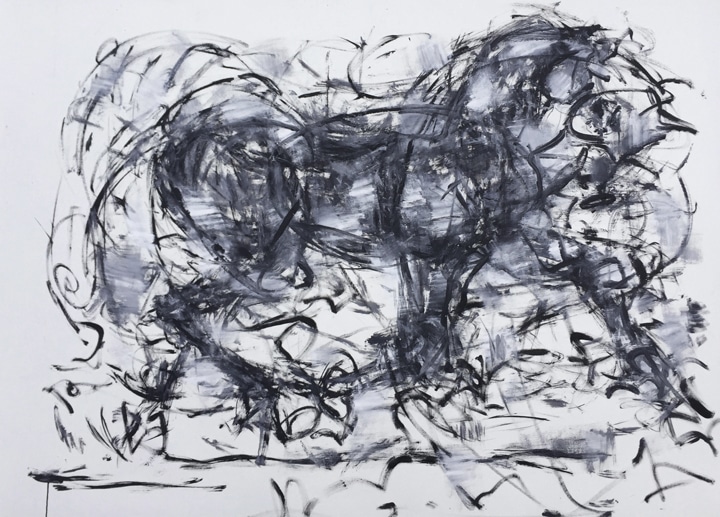

Your works on paper and paintings exude a frenetic energy, almost animalistic. Can you share a bit about your creative process when painting and sketching?

Your works on paper and paintings exude a frenetic energy, almost animalistic. Can you share a bit about your creative process when painting and sketching?

That is a very accurate way of describing it actually. I work very fast on paintings in short blocks of time or rotate paintings so I don’t focus on one too long.

I’m more interested in the abstract idea of a horse than a realistic one. I started off painting very traditionally, going to art school in NYC at Parsons School Of Design, but over the last few years, my interests and focus have changed. I am also shooting photographs a lot aside from the physical paintings and drawings.

The visceral feeling I get from Iceland, and horses in general, I have been trying to capture in my paintings for a while now. I am painting an emotional reaction rather than a visual one.

Your nude self-portraits alongside the horses are immediately striking. What brought about the project?

Your nude self-portraits alongside the horses are immediately striking. What brought about the project?

Putting myself into images with the horses came slightly after a lot of the foundation for my work about nature and horses already existed. I begin placing myself into images as a means of self-examination. I grew up feeling like an outsider socially and didn’t have a lot of confidence and carried a lot of doubts so it started really as a means of exploring these personal issues and trying to understand why I was insecure or lacking confidence.

Then it evolved into more of a means of wanting to be part of the pack with the horses. Philosophers like Thomas Hobbs and his ideas about man always interested me. Man being an animal, having primal instincts and not being separate from nature but just an element in a large ecosystem.

How do you think that man and animal intersect? What does running naked with these animals bring out of you?

How do you think that man and animal intersect? What does running naked with these animals bring out of you?

Like I mentioned above, I think man’s natural instincts are still very much primal and animalistic. On a basic level, I think we are still very much animals, and the overlap is mostly an instinctual one. Running with the horses, or interacting at all in this way, is not quite as romanticized as it appears to be.

All the shooting in Iceland and other parts of the world where I have traveled is more work than anything else. Once you put yourself into these landscapes, especially harsh environments, it becomes very tough on myself and the human body. I find locations and go shoot and sometimes I don’t like the images or I find a few that work. It’s really trial and error.

It’s often a somewhat brutal experience, and I have had a few instances shooting falling, getting kicked or stepped on. It’s hectic and real and not quite as carefree and poetic as it can sound. The end result is what matters, and even in the toughest experiences, there’s always an element of adventure and unknown because it’s controlled only to an extent. Nature is really in charge and the horses. There’s an element of calm and connection that is very satisfying mentally after working through a freezing cold day or something very harsh on the human body and mind.

You mention the series being a method of self-reflection. What did you personally take away from the experience?

You mention the series being a method of self-reflection. What did you personally take away from the experience?

Yes, well the origins of self-portraiture for me are self-reflective in nature and I certainly was trying to sort out insecurities and, in a way, prove to myself I didn’t need to feel this way or carry these emotions around with me. I also feel as though horses were my bridge to nature, something I was comfortable around, and so they were a natural addition to the self-portraits.

I learned a lot about myself, both good and bad I think, during the process. One thing I always wanted to be clear about was I was not exploring vanity, a path driven by ego. So, none of my photographs that involve myself were taken during a high moment in my life. I think almost all of them have been during some form of frustration or internal struggle which helped me deal with some long-standing issues or insecurities I may have had.

Of course, this body of work also led to other interests within it. For awhile I began to want to be one of the horses, not a man posing in their midst. And then, of course, the bigger perspective on social and human instincts and how it has shaped society today, and most importantly, how it shapes our relationship with nature. This is probably even more relevant now with the concerns about our environment and our impact on it.

Society is now so often used to the female nude, even though historically the male nude was a regular part of the art historical canon. Can you talk about the influence of Greek sculpture or Old Master paintings in this respect?

Society is now so often used to the female nude, even though historically the male nude was a regular part of the art historical canon. Can you talk about the influence of Greek sculpture or Old Master paintings in this respect?

This is a great question actually, and I’ve been reflecting on it for a long time because indeed the female nude is far more mainstream in contemporary art and the male nude has very much part of the past and often not as widely accept as “serious” art these days. For me, I spent a lot of time in Europe and lived in Greece for a few years when very young and have been reading about the Greek myths and looking at classical sculpture. I am undoubtedly influenced by this even subconsciously.

Today classicism in contemporary art is rare. Conceptual art, in my opinion, has become the central focus. For me I think it’s very important to have a foundation in learning and being proficient technically I very much admire the large-scale works I learned to paint and draw. I first began to paint huge life size horses, but very stiff and static and slowly that has evolved into this loose line work and mark making that is more about the emotional and energy of the animal than a depiction.

Michelangelo’s David, I still think, is one of the most impressive sculptures I have seen and being exposed the male nude in classical art I never really doubted the relevance of me being a man and putting myself into specific images. When I began to play sports and workout, which I started very young, I found the relevance of not just using this work as an exercise in self-examination of so many social issues I had, but also I felt I could come closely to resembling the art I saw growing up. And also try and adapt this idea of man and animal—trying to compare my body with the horses side by side etc.

I also have some work just me that is posed very sculpturally. They are meant to be very large prints and conceptually to be a contemporary take on some of the old classic paintings that were life-size or even larger than life. My photographs of horses, nature and myself are meant to be seen in this way. Scale is important and, I believe, putting that into context is of the utmost importance when talking about this work.

Do you have any upcoming projects you’d like to share?

I am working on a book about my adventures in Iceland from an intellectual art perspective, but also a personal story perspective, compiled full of sketches and journal pages along with the more finished images and photographs. I hope this type of work that focuses on man’s complex relationship not just with horses, but nature in general also brings more attention to the natural world we are part of and how much we need it and have to find a balance and not try and conquer everything.

Nick Turner: Website | Instagram