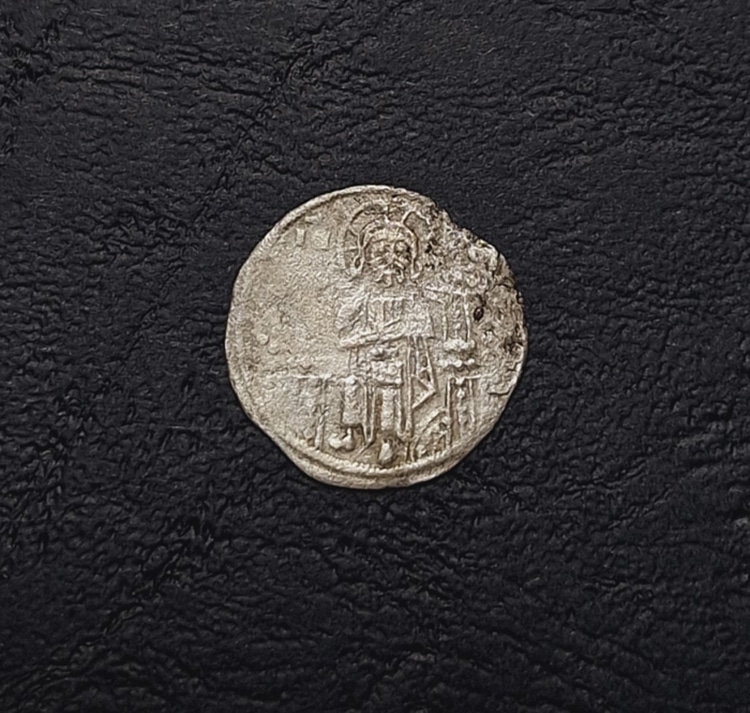

Jesus Christ depicted on the coin. (Photo: Burgas Museum)

Medieval Europe saw many kingdoms rise and fall, and with them coin mints shifted to represent new sovereigns and new currencies. Coins contained precious metals in varying quantities, acting as tangible value in transactions. What a coin bore, stamped into its surface, would often tell the receiver when and where it was minted. Some currencies were renowned and coveted. A fascinating example of medieval coinage has been unearthed by archeologists in Bulgaria, near the southeastern village Rusokastro. Dated to the reign of the Serbian King Stefan Uroš II Milutin, who appears on one side, the coin features Jesus Christ seated in majesty on the other.

The coin features on its reverse a portrait of the Serbian king, who ruled from 1282 to 1321. During this period, he conquered lands to expand his kingdom. He pushed in Bulgaria, where he married (among his five successive wives) a Bulgarian princess named Anna Terter. He also made inroads into Byzantine lands in Northern Greece and Macedonia. Such territory grabs were typical of feudal Europe, and such military endeavors were reflected in Novo Brdo Fortress, which the king built in Kosovo. The coin recently discovered would have been another symbol of his power throughout his lands. It clearly depicts him as a Christian king, as he is seen seated next to St. Stephen. St. Stephen was a very early convert, a first century deacon, and the earliest martyr for the church. The king himself is known to history as the “saint king,” and he was later canonized by the Serbian Orthodox Church.

The king’s piety and the legitimacy of his kingdom are further buttressed by the obverse of the coin, which depicts Jesus Christ. The figure is seated and haloed, possibly enthroned. This image of the seated Christ was a common motif on medieval coins, especially those from the Byzantine Empire. This silver Serbian example demonstrates the influence of Venetian coinage on Eastern Europe. The image of Christ seated clearly copies Venetian pennies known as matapan” or grosso. According to a translated statement from the Burgas Museum, these “were the most stable currency in the Balkans at the end of the 13th and beginning of the 14th century due to their weight and the high quality of silver. However, they represent the Doge, whose name the coin was minted, and St. Mark, the patron saint of Venice.” By replacing the Doge with his own image, the Serbian king indicated his own power and stability. Meanwhile, the discovery in Bulgaria shows the extent of this kingly—and commercial—influence.

This 700-year-old coin unearthed in Bulgaria depicts a seated Jesus Christ on one side, and the king of Serbia and a saint on the other.

The coin, with King Stefan Uroš II Milutin of Serbia (left) and St. Stephen. (Photo: Burgas Museum)

h/t: [Live Science]

Related Articles:

Art History: Ancient Practice of Textile Art and How It Continues to Reinvent Itself

Sister Duo Weaves Textured Wall Hangings Inspired by Australian Landscapes

How to Crochet: Learn the Basics of This Time Honored Handicraft

Artist Fills Forest with Life-Size Sculptures Made from Woven Rods of Willow