Masha Ivashintsova, self-portrait. Leningrad, USSR, 1976.

Asya Ivashintsova-Melkumyan always knew her mother was taking photographs, but never fully understood just how deep this passion ran until recently. When Masha Ivashintsova passed in 2000, she left behind boxes of belongings and memories, which remained untouched until late 2017. It was only then that Asya discovered over 30,000 negatives and undeveloped film—as well as personal diaries—in an attic, all of which detailed the turbulent details of her mother’s life.

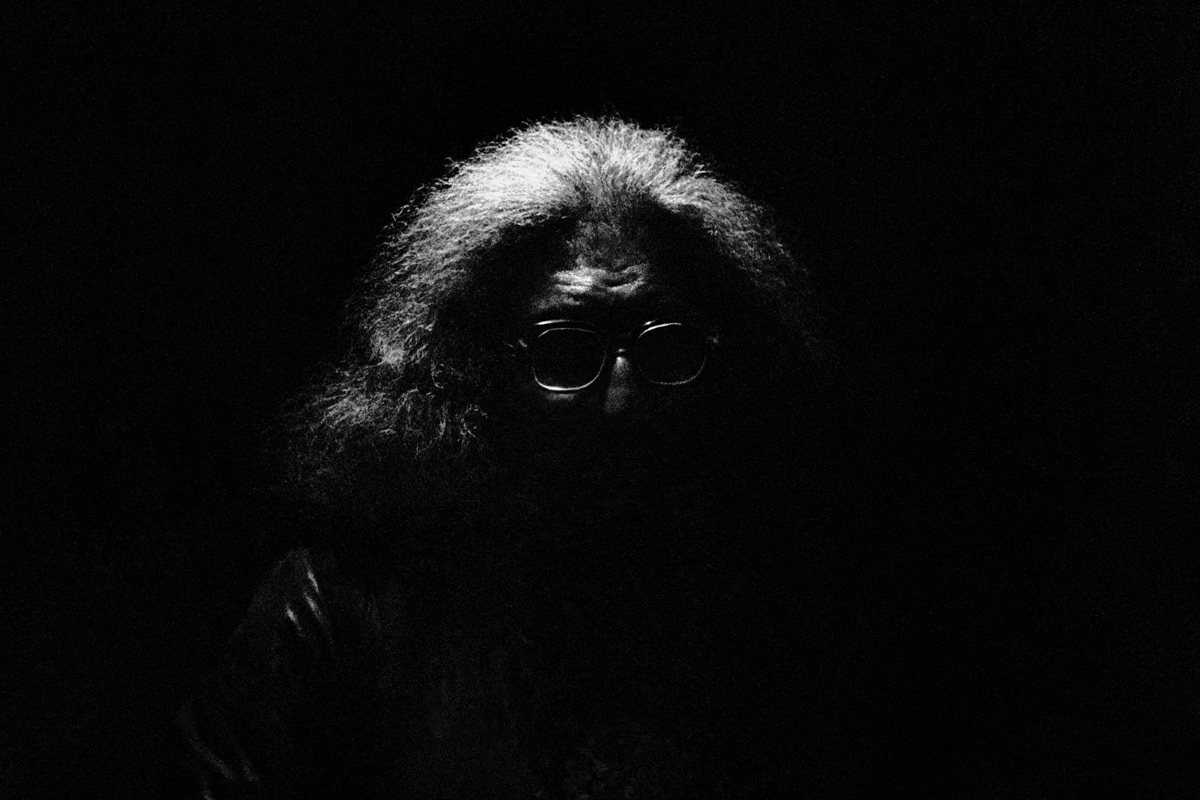

Born in 1942, Masha used photography as a visual journal of her life, taking photographs from the time she was 18 years old up until one year prior to her death. Coming of age in the USSR, Masha was highly involved in Leningrad’s underground poetry and photography movement, and her life was intertwined with three geniuses of the time—photographer Boris Smelov, poet Viktor Krivulin, and linguist Melvar Melkumyan. Melkumyan is Asya’s father, though the family separated when she was young, with her staying in Moscow with her father and seeing her mother during sporadic visits.

Much like Vivian Maier, Masha hid her photographic talents from the world, never showing her work or considering herself an artist in her own right. As Asya writes, “Her love for these three men, who could not be more different, defined her life, consumed her fully, but also tore her apart. She sincerely believed that she paled next to them and consequently never showed her photography works, her diaries and poetry to anyone during her life.”

Asya Ivashintsova-Melkumyan, Masha’s daughter, with dog Marta and cat Pusya. Leningrad, USSR. 1978.

Struggling with life under Communism, by the mid-1980s Masha was committed to a mental hospital against her will, as a way to get her in line with the USSR’s philosophies. Working throughout her life as a theater critic, librarian, cloakroom attendant, design engineer, elevator mechanic, and security guard/riflewoman, she was a chameleon, always camouflaging her inner artist. Only through her diaries and photographs was she able to show her true self.

Since finding the photographs, Asya, along with her husband and two close friends, have been slowly scanning Masha’s work and showing them publicly. Though not without its difficulties, Asya’s project is a loving tribute to her mother, one whose life was not without mistakes but also filled with wonder. We had the opportunity to ask Asya a few questions about her mother’s work and what it means for her to share it with the world.

“I loved without memory: is that not an epigraph to the book, which does not exist? I never had a memory for myself, but always for others.” – Masha Ivashintsova

Moscow, USSR, 1987.

Can you describe the moment when you and your husband first discovered the negatives?

After my mother passed away in 2000, everything that reminded me of her caused great pain and my only longing back then was to clear all of what belonged to her from my sight. Of course, I knew of my mother was taking pictures and that they were probably somewhere inside those boxes. But I never really wanted to open them up. I even tried to give them away to someone who would be interested to have them. But nobody expressed any interest. So, that is why, after her death, I just hoarded them, along with the rest of her belongings into our family attic. photo laboratory, including a Crocus photograph enlarger I gave away to the Saint Petersburg City Palace of Young Creativity (Anichkov Palace).

Last year, we decided that we should clean up the attic in our home in Saint Petersburg. At some point, we stumbled across a big box, which I immediately recognized belonged to my mom. When we opened it up it was full of negatives and prints. They were all carefully packaged in mail envelopes with dates and comments on them.

Leningrad, USSR, 1977.

What was your feeling when you got back the first developed film and saw what your mother was photographing?

I did not really want to look at them since I was afraid it would bring all the memories back. But my husband, who already then was sure that we found a real treasure, borrowed an old scanner from the friends and scanned some of the negatives. When he showed me the developed photographs, my first reaction was reticence, emotional restraint. My pain did not allow me to see. I right away imagined my mother’s fragility, her emotional brittleness. As I expected, the memories were coming back.

Photography had always had a central place in our home, it never seemed significant—taking photographs, for my mother, was like breathing. I also just always assumed that the photography was helping my mother to get through life, I never thought that it was something special.

However, some time passed and my husband Egor, who in the meanwhile got deeper into the archive, managed to persuade me how unique and incredible those works were. That they were bigger than just our family story.

At first, there was only a timid desire to share these negatives with our closest circle. But the value of the photographs was so obvious to anybody whom we showed it to, so soon thereafter we decided to share them with the public. At the time, our close friends joined us in sorting out an archive and working on the public outreach – now we are basically four people (two families) working on this.

Asya Ivashintsova-Melkumyan, Masha’s daughter. Leningrad, USSR, 1980.

It seems like photography was a therapeutic outlet for your mother, to some degree. What role do you think photography played in her life?

For my mother, taking photographs was a very natural process, like breathing, nothing of significance. I think it was helping her to escape reality and her emotions to a certain extent. I remember how emotionally torn she was the whole time—this lies in stark contrast to the calmness of her photography. In this regard, the important find was also my mother’s diaries. Through those, I have had a real revelation of my mother’s internal life—how vulnerable she was and how much she had to go through.

Linguist Melvar Melkumyan, Masha’s husband and Asya’s father. Moscow, USSR, 1987.

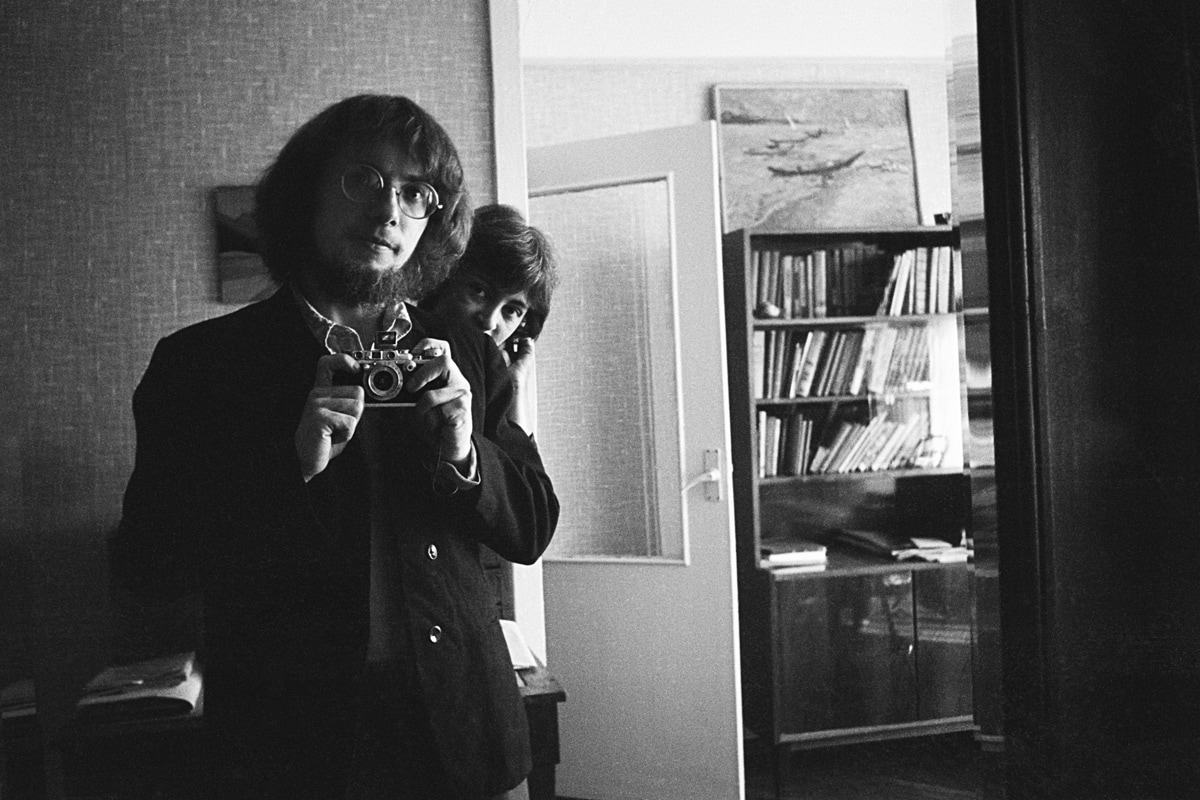

Masha Ivashintsova with her lover, photographer Boris Smelov. Leningrad, USSR, 1974.

Your mother’s photography has started to receive a lot of attention. What does it mean to you to see her work getting so much praise?

It really means a lot to me. I know that her works are worth much more than just to be stuck in our attic. During her lifetime whatever she did was never taken very seriously, neither by her family nor by the men she loved. That’s why I think that it is my job as her daughter now to show her works to the world to make sure she gets the credit she truly deserves.

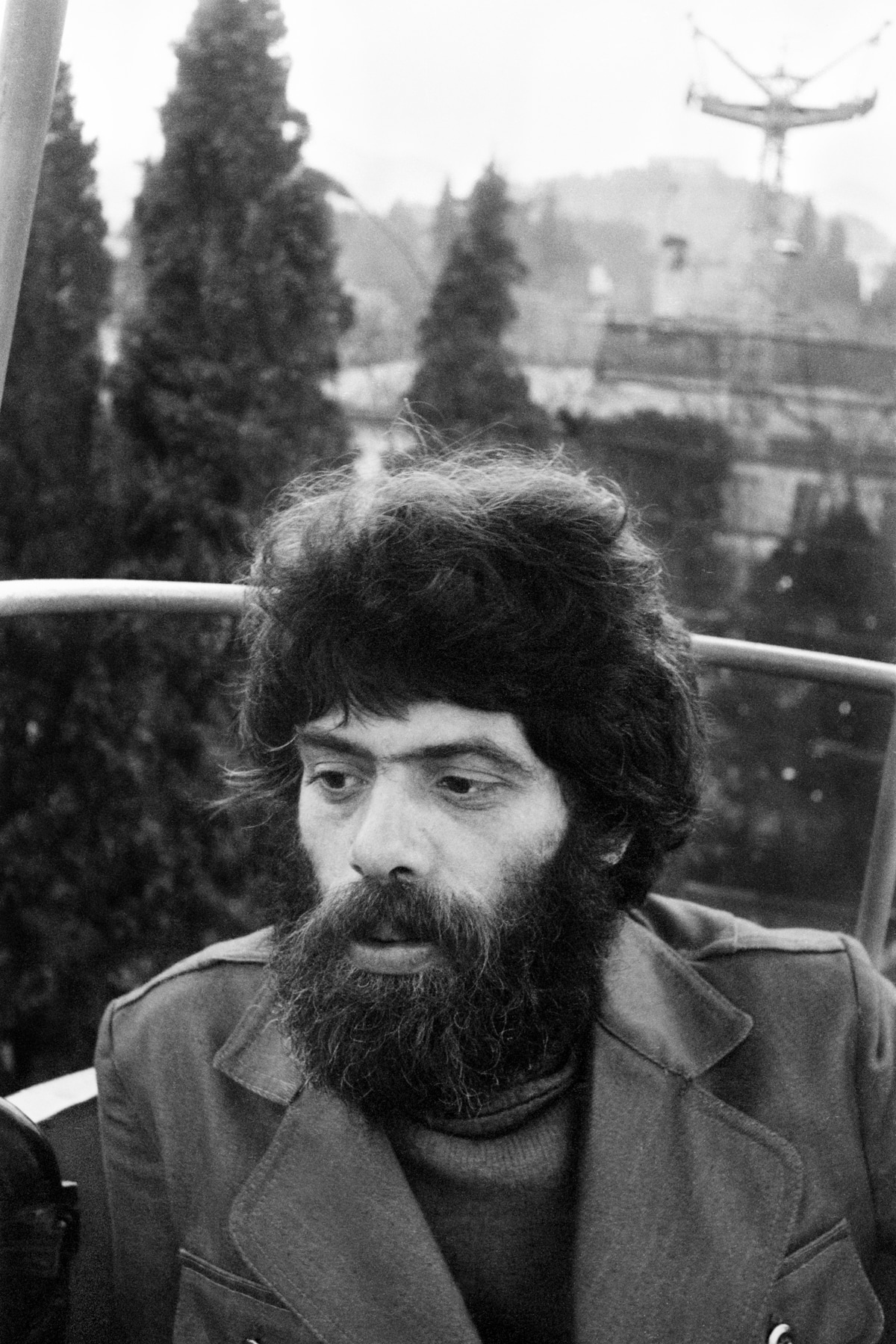

Poet Viktor Krivulin. Yalta, Crimea, Ukranian SSR, 1979.

How do you think she would feel about the attention her photography is receiving?

As regards to my mother, she was a very introverted person, much like myself. I think she would be a bit scared (also as I am now) by the fact that so many people are judging and talking about her work now. But at the same time, I am sure she would be grateful for this appreciation and support that is coming from all parts of the world.

Masha Ivashintsova never showed her photography, even to close family and friends, though she’s been taking photographs from the time she was young woman.

Leningrad, USSR, 1976.

Village near lake Sevan, Armenia, Armenian SSR, 1976.

Though Masha died in 2000, her daughter Asya only recently discovered over 30,000 negatives, as well as her mother’s diaries, in an attic.

Leningrad, USSR, 1978.

Leningrad, USSR, 1975.

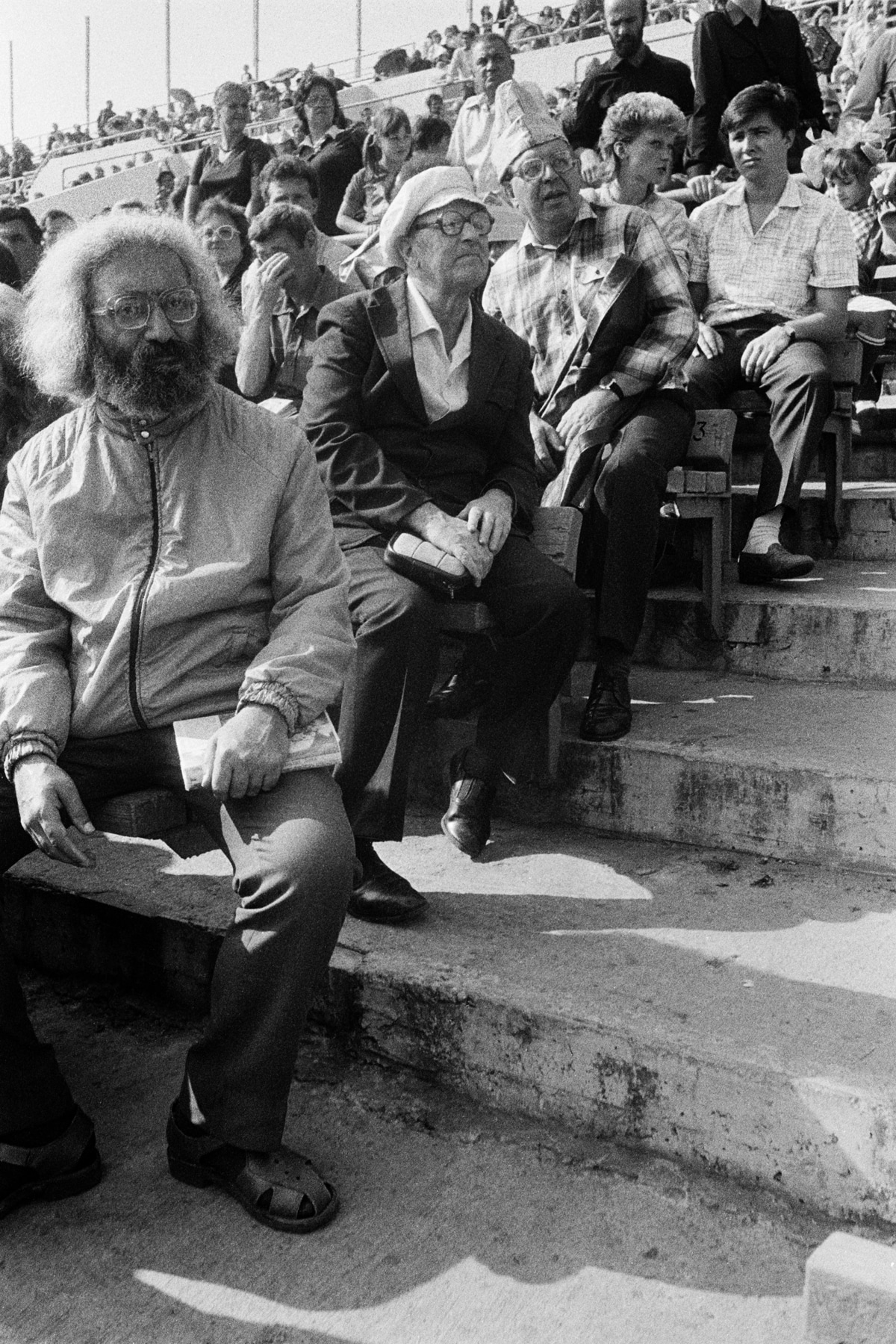

Melvar Melkumyan, Central Dynamo Stadium. Moscow, USSR, 1988.

An introvert, the Russian photographer found comfort in animals and children, both of which feature prominently in her photography.

Vologda, USSR, 1979.

Leningrad, USSR, 1981.

Leningrad, USSR, 1976.

Masha, who spent part of her life in mental hospitals as a way for the Communist regime to control her, is now being posthumously celebrated for her artistry.

Leningrad, USSR, 1978.

Tbilisi, Georgian SSR, 1989.

As Asya, her husband, and two family friends slowly scan the negatives, we can only imagine what other incredible photographs will be revealed.

Leningrad, USSR, 1976.