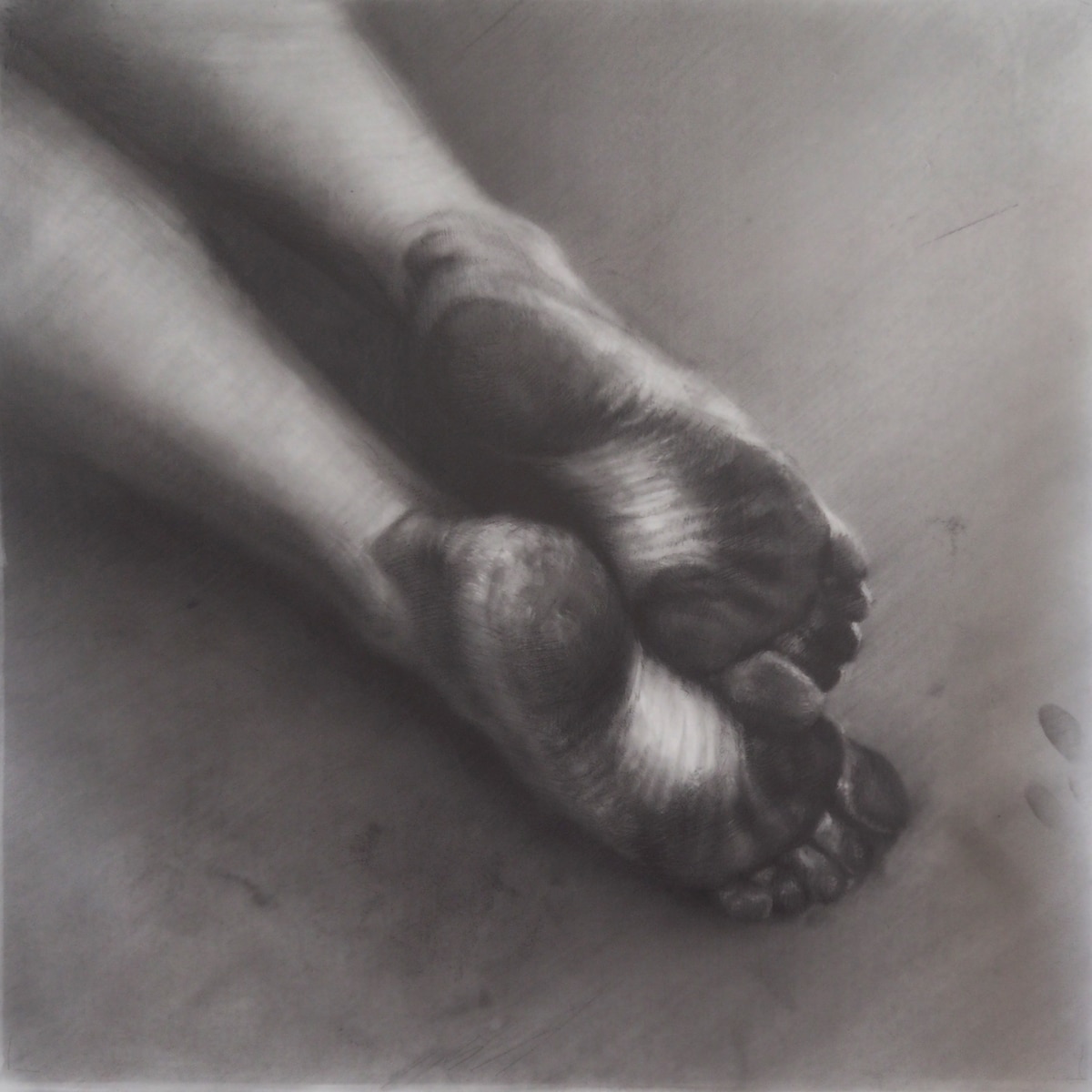

Embrace I (The Horizon). Oil on canvas.

Brooklyn-based Russian oil painter Maria Kreyn‘s Old World sensibilities seep through her paintings. The skilled figurative painter forged her own artistic path, leaving behind studies in mathematics and philosophy to pick up a brush. After time in Norway, where she apprenticed for a master painter for several years, she came away fully embracing oil paint as her medium of choice.

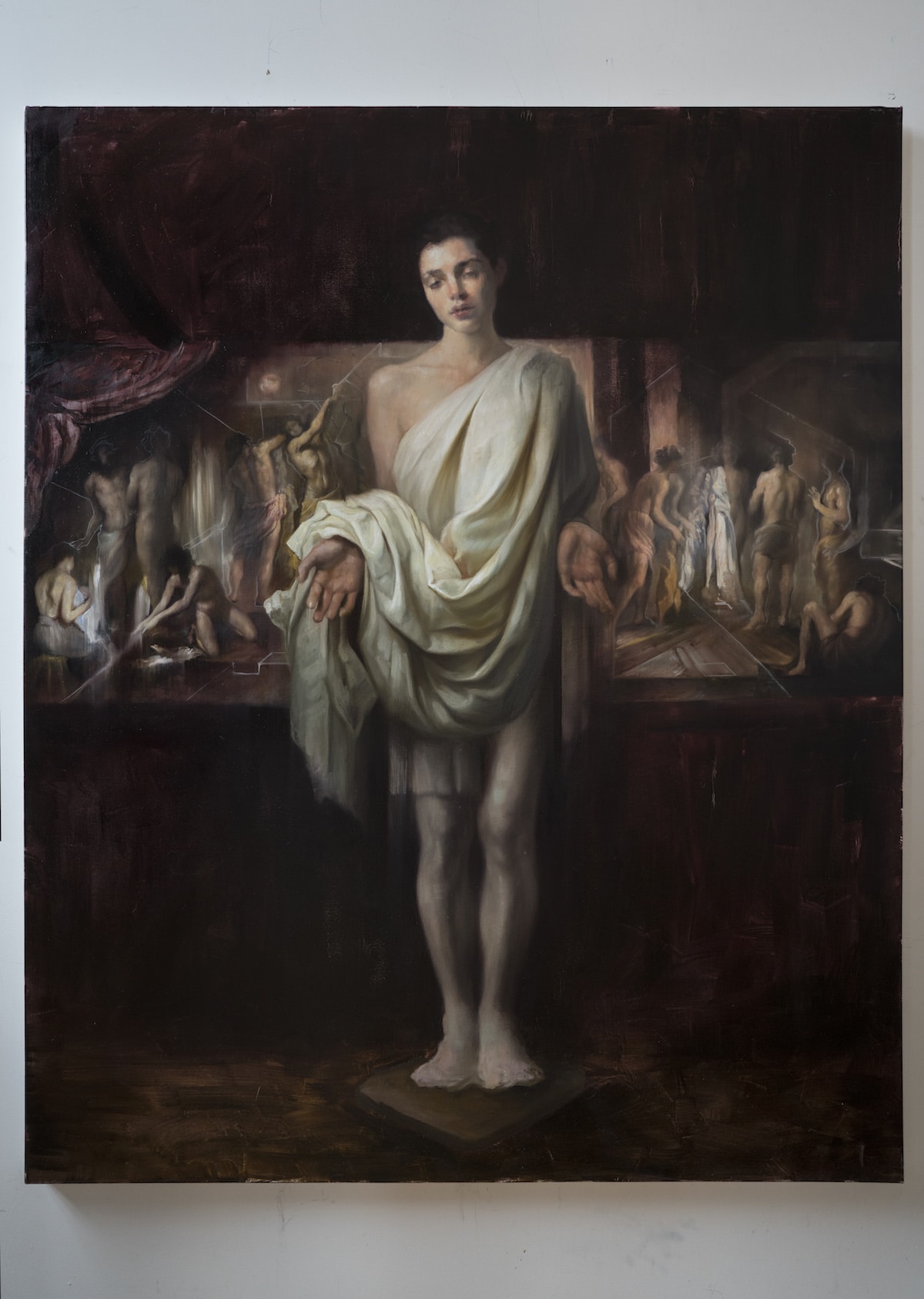

Her canvases, replete with symbolism and allegory inspired by Renaissance and Baroque painters, move toward modernism with their loose brush strokes and dynamic compositions. Kreyn skillfully blends old and new in order to evoke timeless emotions with her work. She also brings forth her background in philosophy, using her knowledge to investigate deeper themes. In The Solipsist, Kreyn depicts a young woman, strong and sturdy as she looks out at the viewer. Solipsism is the philosophy that “only one’s mind is sure to exist.”

As such, Kreyn’s figure personifies the theory. “She is the focus, the center, the raison d’etre. Meeting and firmly holding the viewer’s gaze, her form echoes the stoic compositional structure of orthodox icons. As she seems to rise from a river, her multiple hands imply its continuing motion, resonating with the notion of water as a symbol of the unconscious.”

Maria Kreyn’s exhibition Polyphony runs through May 29, 2018 in the Welsh Chapel, 85 Charing Cross Road, London. For the occasion, we had a chance to speak with the painter about her background and new work.

Embrace I (The Horizon). Detail. Oil on canvas.

Alone Together. Oil on canvas.

You have a well-rounded background that is more reminiscent of the Old Masters than many contemporary artists. How do you think your studies in mathematics and philosophy informs your work as an artist?

I often mine the past for inspiration and I feel like my paintings are an avenue for a kind of personal time travel. I filter my own ideas about the world through old tropes and myths, and remix them to create a personal story. Regarding mathematics, those studies helped me train my mind. As far as philosophy, it’s thought forms are both analytical and mystical—concerning the concrete exigencies of life, and also our abstract and dreamlike states.

In my work, I want to do the same. Painting for me is a philosophical practice, a technical practice, and a sensual one. It’s the way I come to blend and try to understand the dream-like, hallucinatory and emotional states of life with the new science about the brain and mind that I’m interested in learning about.

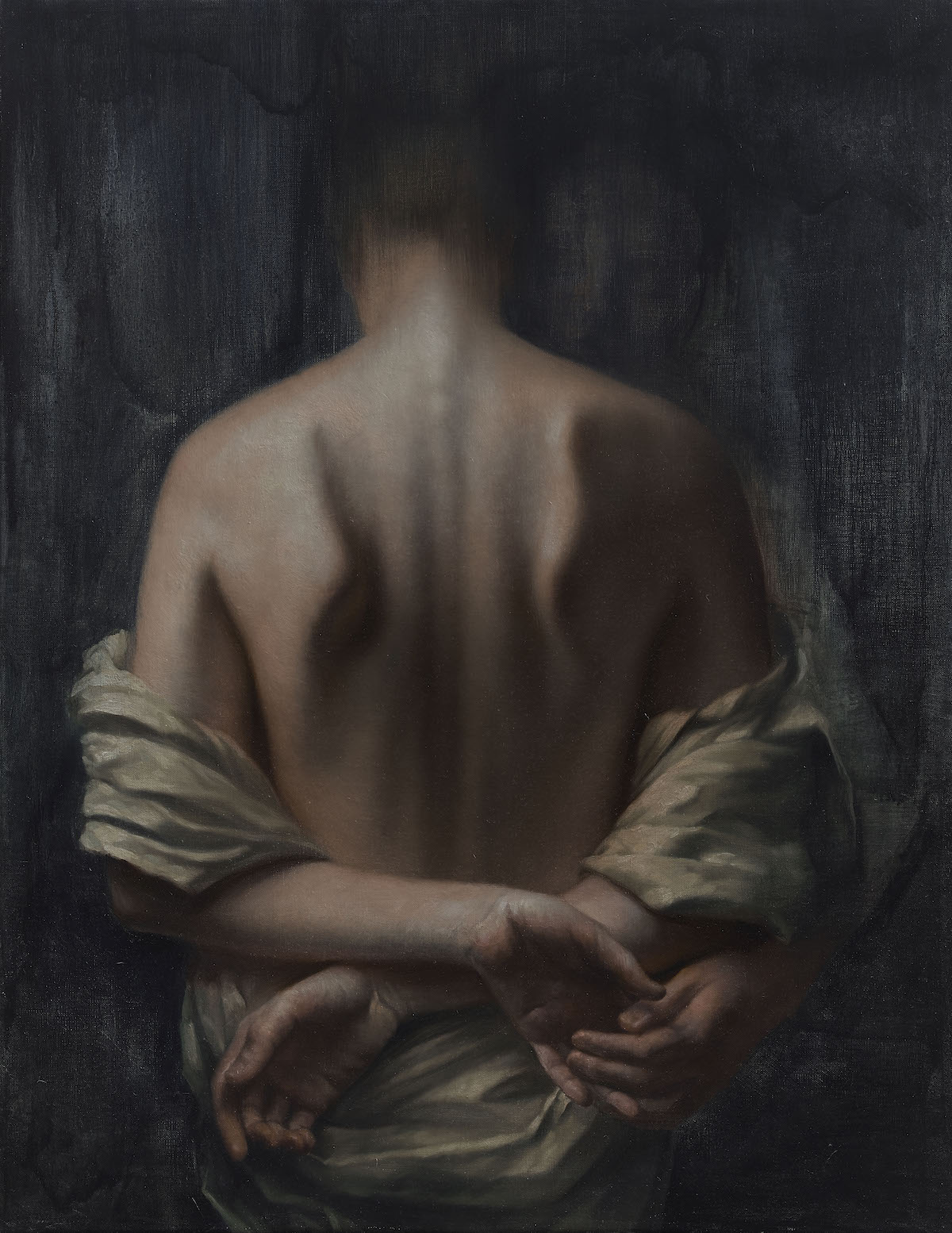

Back. Oil on canvas.

What are the most important lessons you took away from your time apprenticing in Norway?

It was profound to see such incredible dedication to a life of painting. The craftsmanship, the development of personal mythology, the interest in mining the depths of the human condition, the desire and ability to truly move people with art. This time in my life set the bar for what is possible.

The Solipsist. Oil on canvas.

What role does drawing have in your creative process and what’s in your sketching “toolkit” right now?

Drawing is definitely my first love. I refer to my year at the atelier as “drawing boot camp.” And that “toolkit” is what helps free the hand to meet the mind where it wants to wander. It sets one free creatively. That said, technical habits are also meant to be broken and unlearned. Now I draw in a much more erratic way—somewhat procedural, but chaotic, and I use it not only to quickly work out possible ideas, but as an end in itself.

Feet. Graphite on mylar.

Why do you think that the public has seemed to return to embracing figurative painters?

I have a theory here: social media has allowed a vast audience to quickly see a huge amount of artwork. And I believe that, no matter what the fashion, people still love to be emotionally moved. It inspires them, and it lifts a mirror to their own longing and complexity, which is powerful and allows us to feel less alone. Ideology and aesthetic tyrannies have a hard time existing when people have such wide access, and young people are now seeing both intellectual and theoretical value in figurative work. They are able to marry the philosophy and the craftsmanship, and I find that inspiring.

Obscure Object. Oil on canvas.

I love your use of light and shadow. How do you use these elements to draw out the emotional impact of your work?

Chiaroscuro is a powerful technical tool—often moody and turbulent. I feel like the complex and often allegorical vision I’m trying to present is well-served by that aesthetic, amplifying the emotional content inscribed within the gestures of my figures. Even a silent pose, with a static composition, can be made to feel like it’s in a state of movement and emotional complexity.

Embrace II. Oil on canvas.

So many people who are just starting to paint are intimidated by oil paint. What’s your advice for people who are interested in exploring this medium?

Oil paint is intimidating, just like all the good things. I suppose I’d say that they should first learn to draw, because once they tame that dragon, they can ride it.

Eva’s Hands. Oil on canvas.

Artists and art lovers often have one painting by a great artist that has especially influenced them or holds special meaning. What is the one painting that had the biggest impact on you as you were beginning your career, and why?

As a teenager, I fell in love with Leonardo’s John the Baptist, which hangs at the Louvre. With an alien and mocking gaze, he seems to toy with our feelings and desires. He’s androgynous and seductive, and he points up at a god he knows isn’t there, yet seems to have a reverence for all that is living and beautiful. I’ve always loved those qualities in that painting, and I’ve always hoped to infuse my work with even the slightest bit of that.

Memory Recaptured. Oil on canvas.

What do you hope people take away from your work?

I want to move people – to capture them with beautiful craftsmanship, painterly poetics, and an emotional mystery that I hope can linger in their mind and heart.

Allegory of Indecision III. Oil on canvas.

How do you see your art developing in the coming years?

Painting for me is a process of building meaning and, over time, clarifying a personal worldview. It’s a way to sculpt and expand my personal mythscape. I let my mind wander and follow my intuition. So when I come up with an image, it’s usually an autobiographical story encrypted within images that are both borrowed from history and reframed in a new way. I’m striving every day to become a better painter, and I’m looking forward to expanding my practice into sculpture in the coming years.

In the wake. Oil on canvas.

Any projects you would like to share?

Yes! I just opened a show in London, at a beautiful, secret chapel in the center of London, Soho. It’s an important show for me—a celebration of everything and everyone I’ve learned from up to now. What you’ll see in this show is a collection of portraits and large dramatic compositions involving animals and humans. These recent works use allegory to explore ideas of time, self-awareness, and the complexity of intimacy.

The Narrator (Work in progress). Oil on canvas.

The Sieve. Oil on canvas.

Ghosts. Oil on canvas.

Hands. Graphite on mylar.