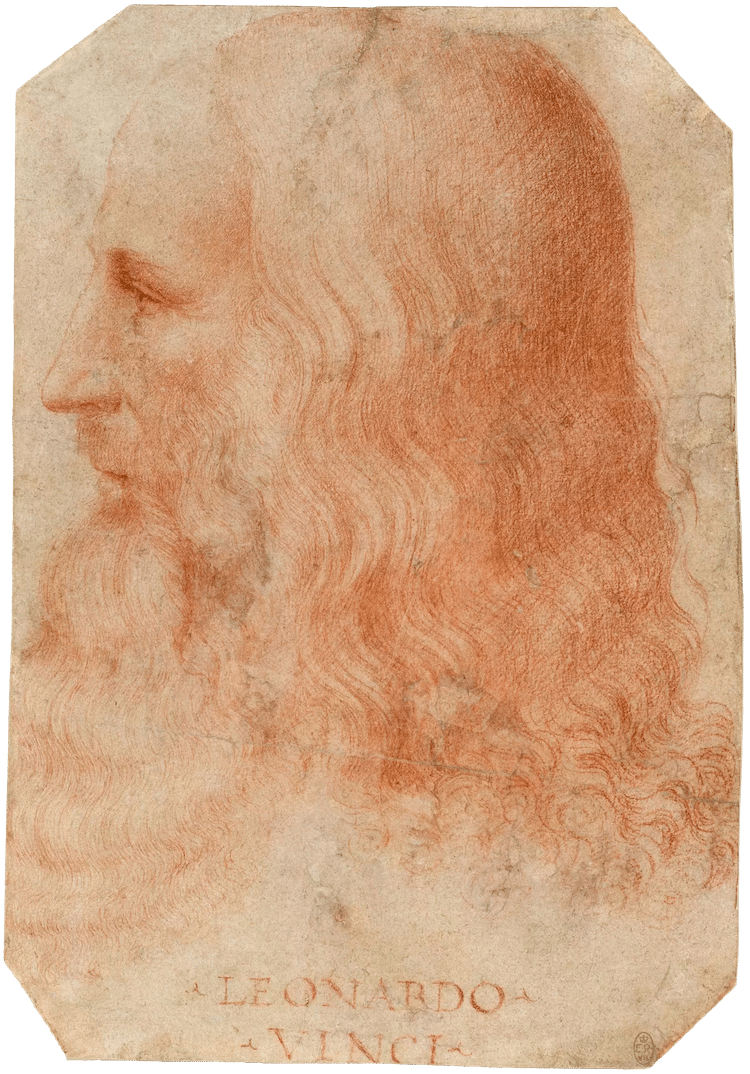

“Portrait of Leonardo da Vinci” attributed to Francesco Melzi, 1515-1517. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

From the Mona Lisa to the Vitruvian Man, so much of Leonardo da Vinci‘s artwork is iconic. The original Renaissance Man, Leonardo was not only a painter, but also a scientist, musician, engineer, and mathematician. Many of his scientific musings and theories were later discovered to have a basis in fact and his paintings have made an indelible mark on art history.

Together with Michelangelo and Raphael, Leonardo is considered one of the pillars of the Italian Renaissance. Born in 1452, his career began when this great period of art was heating up, and he continued to keep up with his younger colleagues throughout his career.

So what do we know about the life of this great thinker? Where did his thirst for knowledge come from and where would it take him? As one can imagine, his love of learning and his creative mind led him in many different directions. Let’s take a look at some interesting facts about Leonardo da Vinci’s life in order to get a better understanding of his incredible mind.

14 Facts About the Original Renaissance Man, Leonardo da Vinci

“Virgin of the Rocks” by Leonardo da Vinci, between 1483 and 1486. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

|

Full Name

|

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci

|

|

Born

|

April 15, 1452 (Vinci, Italy)

|

|

Died

|

May 2, 1519 (Amboise, France)

|

|

Notable Artwork

|

Mona Lisa, Vitruvian Man

|

|

Movement

|

Italian Renaissance

|

He had no real last name

Though often referred to simply as “da Vinci,” the reality is that Leonardo did not have a last name, at least not as we think of it in the modern sense. Da Vinci literally translates to “of Vinci,” which is his hometown. This was common at the time. During Leonardo’s lifetime, hereditary surnames become more popular with the upper class but wouldn’t be common practice until the mid-16th century. That’s why you’ll still find that most museums and academic books simply refer to him as Leonardo.

He was an illegitimate child

Leonardo was born out of wedlock to Ser Piero, a wealthy Florentine notary, and a young peasant named Caterina. Leonardo’s mother married an artisan shortly after his birth.

Leonardo was treated as the legitimate son of Ser Piero and grew up on his family’s estate. He also had 12 half-siblings from his father, who were far younger than him and with whom he had little contact.

He didn’t have a formal education

For all of his genius, it might be surprising to know that Leonardo didn’t receive much formal education. He learned the basics of reading, writing, and arithmetic, but much of his deep learning came later in life.

For instance, Latin, which was the language of academics at the time, was something he largely taught himself. And advanced mathematics, a topic he was passionate about, only entered his life in his 30s when he started devoting himself to the subject.

He was left-handed

There are some studies that suggest left-handed people are more creative; and, if true, that is certainly the case with Leonardo. The Renaissance man is one of the most famous artists that is confirmed to have had a dominant left hand. Recent historians believe that Leonardo may have even been ambidextrous.

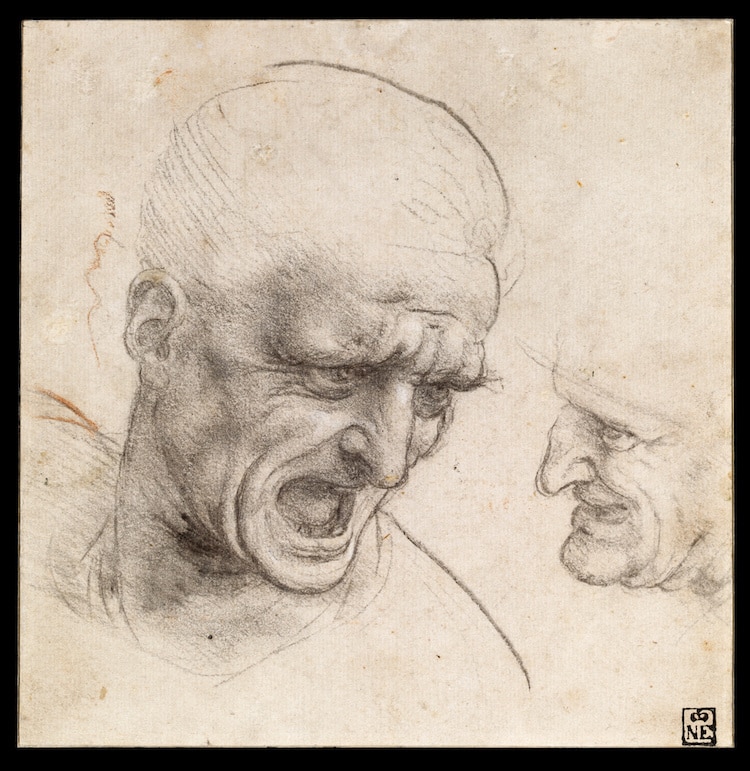

“Study of Two Warriors’ Heads for the Battle of Anghiari” by Leonardo da Vinci, 1504-1505. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

He didn’t paint that much

Though Leonardo is considered one of the greatest artists of all time, his artistic output was relatively small. In fact, there are only about 17 surviving works that can be definitively attributed to him.

Part of this was due to his busy mind. Occupied with scientific research and engineering matters, he often went through long stretches where he wasn’t accepting commissions or painting much.

Some of his famous works, like The Battle of Anghiari and Leda are known only through preparatory sketches or copies made by other painters after having been lost, destroyed, or deteriorated over time. However, his unparalleled reputation speaks to the power of his artistry. Even with so few complete paintings, it’s impossible to deny his influence on artists of his own day and for generations to come.

He started apprenticing at 15

As was typical at the time, Leonardo began his artistic training as a teenager. Thanks to his father’s good reputation, he was able to enter into the studio of respected artist Andrea del Verrocchio at age 15.

It was here that he would not only learn the basics of painting and sculpture, but also engineering and technical arts. This included things like chemistry, drafting, metallurgy, and metalworking. At the same time, he also worked in the workshop of Antonio Pollaiuolo, as it was located just next store.

At 20 he was accepted into Florence’s painter’s guild but continued to spend the next five years under the tutelage of Verrocchio before branching out on his own.

Notebook study of a Fetus by Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1510-1513. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

He was fascinated by the human body

Leonardo’s thirst for knowledge also extended to the human body. Not content to study what was already out there, he deepened his knowledge by performing as many as 30 human dissections at hospitals in Milan, Florence, and Rome.

His passion for anatomy grew so much, that it became its own area of study for the artist, independent of how it influenced his artistic work. From early on, he was not only interested in the structure of anatomy, but also started physiological research. His drawings that show how the brain, heart, and lungs function as the core of the body are still known as a great achievement in science. In fact, his anatomical drawings helped lay the basis for modern scientific illustration.

He was an animal-lover and possibly a vegetarian

Many sources—including Leonardo’s notebooks and the writing of his contemporaries—have described Leonardo’s passion for animals and wildlife. Moreover, he challenged the morality of consuming animals in his writing. Altogether, this evidence strongly suggests that he was a vegetarian.

Renaissance art historian Giorgio Vasari recounted a story of Leonardo, in which the young artist would purchase birds for sale so that he could set them free.

He was great at music, too

According to Vasari, Leonardo’s talents also extended into the musical sphere. Not only was he described as an accomplished singer, but he was also talented on the lyre and wrote musical compositions in his notebooks. He even created a silver lyre that was shaped like a horse’s head—an item that was later gifted to Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan.

Bill Gates owns his notebook

With such a great appetite for knowledge, it should come as no surprise that he was a prolific writer. Many of Leonardo’s notebooks are in prominent institutions like the British Library and the Victoria & Albert Museum, but one, in particular, is in the hands of a modern genius.

Leonardo’s Codex Hammer, also called the Codex Leicester, was purchased by Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates in 1994 for $30.8 million.

The 72-page notebook was written between 1506 and 1510. It contains a number of scientific musings on everything from the reasons why the sky is blue to the luminosity of the Moon to how the movement of water works and how fossils originated.

Studies of Horses by Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1490. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

He wrote backwards

As a left-hander and frequent writer, Leonardo filled his notebooks with a mirror script—which is a mirror image of normal text. It is theorized that this approach was probably faster for him, as he could write from right to left. In addition, he created a variety of symbols that he inserted within his notes. These strategies also disguised the content of his writing at first glance.

His greatest work was ruined by war

Leonardo is well-known for iconic artwork like the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, but, unfortunately for us, his greatest work was never fully realized.

In 1482, Leonardo left Florence for Milan, apparently lured there by a commission for an enormous equestrian statue honoring Francesco Sforza. When completed, it would have been larger than the other two equestrian statues of the Renaissance done by Donatello and Leonardo’s old mentor Verrocchio.

It would have been over 16 feet tall and was commissioned by Sforza’s son, who was the Duke of Milan. Leonardo toiled for 17 years on the project, which was given the nickname Gran Cavallo (Great Horse). The long timeline wasn’t unusual for Leonardo, given his pursuit of other interests.

After 12 years, in 1493, a clay model of the sculpture was put on display and Leonardo worked on detailed plans to cast it in bronze. Unfortunately, the metal that was to be used for the sculpture was instead designated for cannons, as the threat of French invasion was imminent. In fact, the Duke was overthrown in 1499 and the clay model was ruined as French troops invaded the city, robbing us of what would have been one of the great monuments of the Renaissance.

He worked as a military architect and engineer

A few years after the end of the equestrian sculpture, Leonardo entered into an agreement with the notorious Cesare Borgia. Son of Pope Alexander VI, he was commander in chief of the papal army and known for the ruthless way he maintained control and tried to dominate different Italian states.

Leonardo spent 10 months as a “senior military architect and general engineer.” As such, he traveled around Borgia’s different territories to survey them. He also created many city plans and topographic maps, which foreshadow modern cartography.

He spent his later years in France

When Leonardo was 60 years old he was forced to leave Milan due to political upheaval. This led him to Rome, where he was hosted by Giuliano de’Medici, brother of the Pope. While Leonardo was hoping to find work in Rome, he was simply given a stipend and left to his own devices while other artists like Raphael and Michelangelo were hard at work on commissions for the Pope.

This frustrated Leonardo greatly and so, five years later, he gladly accepted an offer by the king of France to come work for him. He left Italy at age 65 in 1516 and never looked back. While he didn’t do much painting while in France, he spent a lot of time working on his scientific projects. He died just a few years after arriving in France and was buried in the Collegiate Church of Saint Florentin at the Château d’Amboise. Unfortunately, the church was damaged during the French Revolution, which led to its demolition in 1802. As some of the graves were also destroyed, this has made it difficult for historians to know where his remains are.

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

Leonardo Da Vinci’s To-Do List Proves He’s a True Renaissance Man

All 1,119 Pages of Leonardo Da Vinci’s “Codex Atlanticus” Now Available Online

View Leonardo Da Vinci’s Notebooks Online and Go Inside the Mind of a Genius

Secret Drawings Have Been Discovered Underneath a Priceless Leonardo da Vinci Painting