La Madeleine in Paris. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Paris’ La Madeleine is not a tasty pastry, but rather a Neo-Classical masterpiece of French architecture. L’église Sainte-Marie-Madeleine—or the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene—is a landmark of the French capital. Finished in the 19th century, it boasts magnificent columns and is full of marble sculptures and gilt decorations. It once hosted the composer Chopin’s funeral and eventually came to represent the glory of 19th century Paris.

Read on to learn more about the history of this must-see house of worship, and be sure to visit it when you get the chance.

Interior view of La Madeleine, Paris. (Photo: Joe deSousa via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

Church Planning During Ancien Régime

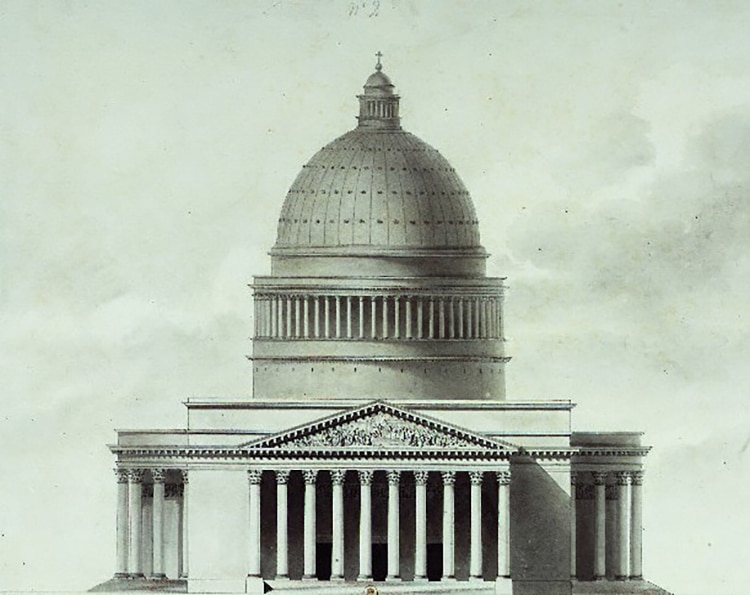

Design by Etienne-Louis Boullée for “une l’église de la Madeleine” which was never realized. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The present-day neighborhood known as 8th arrondissement of Paris once held the medieval Ville l’Evêque. This region has possessed a church dedicated to Mary Magdalene since at least the 13th century. The urban center of Paris steadily expanded throughout the early modern period. By the 18th century, the 8th arrondissement was a busy, official part of the city. Plans for a new and larger Catholic Church were in the works.

France during the Ancien Régime was run by powerful, absolute kings. In 1755, a large square abutting the Jardin de Tuileries (Tuileries Garden) was christened the Place Louis XV, the reigning monarch. From this square, la rue Royal (Royal Road) extended towards the new site chosen for the to-be grand church. This location at the nexus of royal power and grandiose architecture would send a powerful statement to the citizens of the city.

The first design for the new church was by the architect Pierre Contant d’Ivry. He imagined a Latin cross with a large dome. Constant d’Ivry died in 1777 with only the preliminary building complete. Guillaume Couture then took over the supervision of the project. He destroyed much of what had been built in favor of a plan modeled on the classical Pantheon in Rome. Building projects often took decades, and the efforts to create a church worthy of the royal family were foiled by the French Revolution.

Napoleon and the Foundation of the Present-Day Church

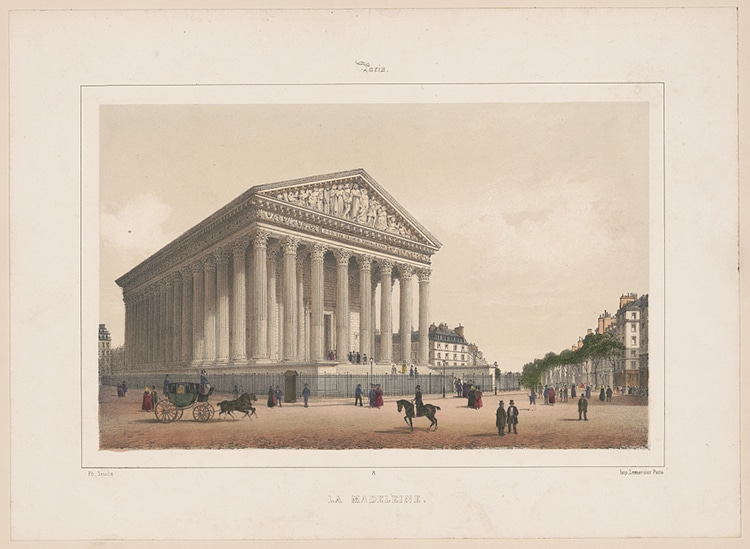

“La Madeleine,” by Phillippe Benoist, between 1845 and 1860. (Photo: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

The French Revolution—which spanned the 1790s—was a turbulent time. The king and queen lost their heads, as did (eventually) the man who guillotined them. In the power vacuum created by turmoil, the military leader Napoleon Bonaparte staged his own successful coup in 1799. By 1804, he was the self-crowned Emperor of France. He would later commence a campaign across Europe in a quest for territorial expansion.

Napoleon’s military focus inspired a new use for the building site of La Madeleine. First, a stock exchange was considered. Then, Napoleon decided on a “temple to the glory of the French army.” Lead by Pierre Vignon, the beginnings of the church were removed and new construction began once more. However, Napoleon’s empire was short-lived. By 1815, the Treaty of Paris and the deposed emperor’s exile to Saint Helena resulted in a restored monarchy under King Louis XVIII.

With a restored monarch and a renewed Catholic Church, building commenced once more. Yet French politics rarely ran smooth. Vignon remained in charge, but his death in 1828 caused another delay. Then, there was political turmoil in 1830 as the old Bourbon ruler was ousted for the July Monarchy, a regime that continued until the Revolution of 1848. However, despite the climate of the nation, building continued. The church was finished and officially opened for worship in 1842.

La Madeleine and La Belle Époque Period

“Sortant de la Madeleine, Paris,” by Jean Béraud (1849–1936). (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The finished La Madeleine church gives the outward appearance of a Roman bath with a Neo-Classical design based on an actual Roman temple—La Maison Carrée in Nîmes, France. Enormous Corinthian columns surround the rectangular structure including a deep portico (porch) entrance. Above the doors is a lofty triangular pediment carrying a frieze of the Last Judgement by Philippe Joseph Henri Lemaire. In the sculpture, Mary Magdalene asks for mercy upon sinners. Inside, three domes sit atop a nave that leads to an altar with a statue of Mary Magdalene above it. Frescoes and gold gilding decorate the interior (including a depiction of Napoleon). A monumental organ created by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll fills the church with song.

La Madeleine began as a royal project which took on an imperial edge. The building was consecrated only a decade before the fall of the monarchy once more and the institution of the Second Empire in 1852. This empire lasted until 1870. Under the rule of Napoleon III, Paris was thrust into modernity by the renovations of Georges-Eugène Haussmann. Paris had grown in a haphazard fashion since Roman days; its twisty, narrow streets and dense neighborhoods lacked the modern conveniences befitting a center of an empire.

Haussmann’s answer was to combine public works on necessary infrastructure with the destruction of countless dense, crowded, impoverished neighborhoods. Through these areas, he placed the grand, tree-lined boulevards so familiar to tourists in the Paris of today. Among these boulevards were monuments, squares, and gardens. This new plan of Paris highlighted landmarks such as La Madeleine, grand examples of a flourishing city entering La Belle Époque full of art and music.

20th Century to Today

The altar featuring a statue of Mary Magdalene flanked by angels. (Photo: MARGARITAGLOTOVA/DepositPhotos)

On the outside, La Madeleine looks much as it did in the 19th century. Inside, the organ is still used and worship is still held. Tourists flock to the building, much as celebrants once did at the end of the Great War. Run by the Archdiocese of Paris, the church also hosts countless classical concerts.

A visit to La Madeleine is not complete without wandering the neighborhood full of luxury shopping and 18th-century chateaus. Meander to the Place de la Concorde where you can gaze upon the Hôtel de la Marine and the Hôtel de Crillon. From La Madeleine, historic Paris is within reach.

Pediment of La Madeleine, with a sculpted “The Last Judgement” by Henry Lemaire (1833). (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Related Articles:

Notre-Dame in Art: How the Medieval Cathedral Has Enchanted Artists for Centuries

Photos of Abandoned Churches Display the Decadent Beauty Left Behind in Ruins

9 Facts About the Pantheon, the Iconic Roman Church That Barely Survived the Dark Ages