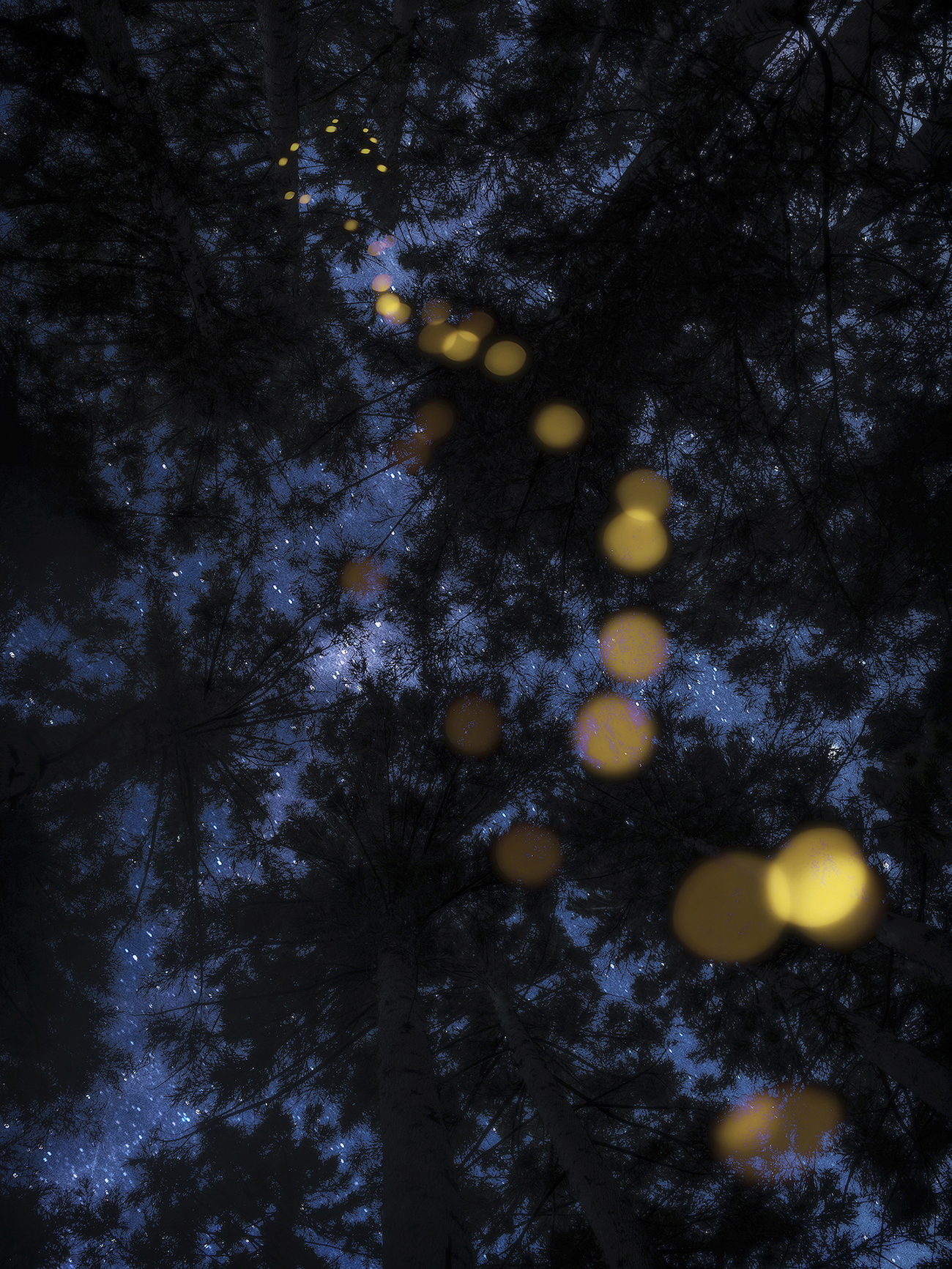

“Shining Forest,” 2018.

Every summer, Japan’s forests bear witness to magic. Thousands of fireflies, or himebotaru, drift through the night sky, emitting a soft glow not unlike that of a candle or a star. Against the thick leaves, these insects almost resemble fairies, a comparison that has not gone unnoticed by photographer Kazuaki Koseki.

For the past eight years, Koseki has pursued himebotaru throughout Japan’s Yamagata prefecture, a region in which they’re an endemic species. It’s become a summertime ritual for the photographer, during which he descends into the Yamagata woods and, using a long exposure technique, captures himebotaru with his camera. The resulting photographs pulse with constellation-like clusters, the fireflies swarming the lush ferns and towering trees.

There’s a certain tenderness guiding Koseki’s work. The himebotaru phenomenon occurs for only a few days each summer, forcing a quick yet considered reaction to its ephemerality. Koseki understands the importance of taking advantage, while also revealing the landscape’s magic, especially as deforestation, climate change, and natural disasters threaten it.

Now, Koseki has collected these photographers into the Summer Faeries series. In March, Summer Faeries will be exhibited at the 2025 Tiradentes Photography Festival in Brazil. It will also be showcased at the 2025 Photo London Fair in May.

My Modern Met had the chance to speak with Koseki about Summer Faeries, the himebotaru phenomenon, and his creative process. Read on for our exclusive interview with the photographer.

“The Gods Live,” 2018.

What originally inspired you to photograph fireflies?

There are many species of fireflies in Japan, but the most common species are the water insects, Genji botaru and Heike botaru, and the terrestrial insects, Himebotaru, which I’m photographing in the Summer Faeries series.

Eight years ago, when I first learned of the existence of these himebotaru, I wondered if they existed in the nature of Yamagata as I know it. I opened a detailed mountain map and researched the forests that might be inhabited. When I found a spot, I drove my car deep into the forest and started walking alone into the night without any moonlight.

The uninhabited forest at night is the territory of beasts, and although I felt a strong fear of the forest at night, I walked deeper and deeper. After about 30 minutes, I found a small yellow light that seemed to twinkle, and when I switched off the light, countless small lights were twinkling in the forest.

After a while, my eyes became accustomed to the darkness and the silhouettes of the forest began to faintly appear and countless lights continued to glow. It was like a starry sky twinkling. The darkness of the forest, which was terrifying, continued to spread out before my eyes as the most beautiful forest I had ever seen, thanks to their countless twinkling lights.

When I returned home that night, even after some time had passed, the sight did not disappear from my mind, which could be described as an emotional experience. What kind of image did the light I saw in the darkness give to my brain? The dialogue with myself continues to this day. And so the project began, exploring nature, ecology, and various phenomena, including the forests where they live.

Spending my days in the nature and climate, spiritual features of Tohoku and Yamagata, the changing seasons that I experience with all my senses, bring me a lot of inspiration. In March 2011, the Great East Japan Earthquake struck the east coast of Tohoku, including Miyagi Prefecture, where I lived when I was younger. Seeing my friends die and so many others affected, I learned about the ferocity of nature and the fragility of life. These experiences were a very big driving force for me to start creating my artwork.

“Tanabata,” 2020.

“Summer Forest Faeries,” 2023.

“Lights of Life,” 2021.

“Get Lost in the Fog,” 2022.

How would you explain the himebotaru phenomenon to those who are unfamiliar with it?

Fireflies fly up from the ground about 30 minutes after the sun has set and fly around in the dimly lit forest, flashing their light at intervals of 0.4-0.5 seconds. The spectacle is like the twinkling of a starry sky.

These behaviors occur when the fireflies become adults and the male flies around in the forest, emitting light, while the female, whose hind wings have degenerated and cannot fly, glows in the grass. For a mere ten days or so in early summer, this courtship behavior, which is intended to pass life on to the next generation, is an activity that reminds us of the beauty and fragility of life at the same time.

“Path of Himebotaru,” 2018.

“Layer of Lights,” 2018.

“Journey to Rowan,” 2021.

“Full Moon Flower,” 2022.

“Gate of God Area,” 2018.

You’ve been photographing fireflies for the past eight years. Throughout that time, how have your photographs or creative process changed?

This series of works was shot using long exposures. The length of each shutter speed ranges from 10 seconds to 5 minutes.

The forest is observed, composed, and the camera is set up on a tripod before the sun has set. This process of composing sometimes takes a long time, and some compositions have taken several years to achieve.

What is important is to imagine the forest in the dark and express its essence and beauty, as the way the forest looks—or appears—changes dramatically when it is dark. There is a density to the darkness, affected by the moonlight, as well as distant city lights that are reflected in the sky and clouds. Even the amount of white clouds and starlight changes with the time of day. The forest is illuminated by these very small amounts of light.

Another technique is to predict which altitude and route fireflies prefer to fly and to capture the parabolic lines they draw. Fireflies’ unpredictable light trails are determined by a variety of factors, including the density of darkness in the forest, the terrain, and the vegetation. In photographing with long exposures, the final image is obtained by the light drawn irregularly by the fireflies.

Himebotaru is also an artist who paints light in the forest. Summer Faeries is a dialogue and exploration between me, the forest, and the fireflies, which continues every night for about three weeks in early summer.

In the early years, the most important thing was to show the entire time during which fireflies fly in a night (1.5 to 2 hours). In the medium term, the overlapping of time was expressed by multiple exposures at the same location.

Currently, the emphasis is on depicting the diversity and unpredictability of the firefly’s light trails in a shorter period of time.

“Forest Serenade,” 2020.

“Courting Soul,” 2023.

“Ancient Memory,” 2021.

“Golden Forest,” 2020.

How has our ongoing climate crisis impacted the himebotaru phenomenon?

They have lived uninhabited in deep forests for a long time. Especially in the last 100 years or so of modernization, much of the forest has been cut down for various reasons, leaving no place for them to live unnoticed—farmland, pasture, roads, places for people, tourism developments, and things of that nature. The fireflies we see today are those that have escaped such threats.

There are concerns that the torrential rains and wildfires caused by climate change in recent years could damage firefly forests. With the development of solar and wind power, which is being promoted for environmental protection, forests are also being cut down. They live under constant threat in modern times.

A few years ago, torrential rainfall, probably due to recent climate change, hit the fireflies’ habitat, and when we visited the day after the rain, we could not see them glowing in the forest. Fortunately, the fireflies’ behavior resumed as usual the following year. Firefly eggs need adequate moisture to transform into larvae, but the possibility that excessive rain will wash them away may not disappear in the future.

In recent years, temperatures have been rising and Yamagata has been experiencing an increasing number of years with very little snow. In years with less snow, fireflies are more active and fly around more, probably because less snow means they can stay active longer and survive by feeding on more prey.

Although they naturally prefer warmer climates, they live in harsh, snowy terrain. If the forest environment exists, they may survive more robustly than expected, adapt to the present-day Earth and thrive far longer than we humans will.