Photo: Stock Photos from Valeria Cantone/Shutterstock

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

Japanese rock gardens—or Zen gardens—are one of the most recognizable aspects of Japanese culture. Intended to stimulate meditation, these beautiful gardens (also known as dry landscapes) strip nature to its bare essentials and primarily use sand and rocks to bring out the meaning of life.

Today, Zen gardens are not only featured at historic Japanese temples, but are also often constructed in residential properties around the world, where a bit of tranquility is needed—not to mention the tiny rock gardens that people leave on their desks. No matter what the size, the purpose of the Zen garden remains the same. Through its form, it allows viewers to clear their minds and move into a meditative state.

While they’re highly recognizable, what is the purpose of a Japanese rock garden? And how did Zen gardens come about? Let’s look at the history of how sand and stones transformed culture, as well as some of the world’s best Japanese rock gardens.

The History of Zen Gardens

Japanese rock gardens came about with the rise of Zen Buddhism. Zen philosophy was introduced into Japan from China in the 12th century and became quite popular with samurais and warlords who admired it for its focus on control and self-discipline.

Photo: Stock Photos from Slavko Sereda/Shutterstock

In the 14th and 15th centuries, during the Muromachi period—which was happening at the same time as the Italian Renaissance—special gardens began to appear at Zen temples. Particularly in Kyoto, which is still home to some of the most incredible Zen gardens in the world, monks began designing rock gardens that had esoteric meaning.

By stripping out water features and using stones, they were making a timeless landscape that was almost abstract in form. In China, compositions made from stones were already common, but this usage in Japan was revolutionary at the time. Water was represented carefully raking the sand into wavelike patterns, while the garden was often designed to be viewed from one perspective on a platform.

The white sand doesn’t only represent water, but also provides negative space in the composition and therefore emptiness. Instead, the rocks are used to represent different elements of a typical landscape—islands, mountains, trees, and animals. Arranged in a balanced (but not symmetrical) fashion, and often in groups of threes, the seeming simplicity of a Japanese rock garden reveals complex ideas through meditation.

With such meaning behind Zen gardens, it should come as no surprise that the world’s oldest garden planning manual—Sakuteiki—was published in the 11th century to help practitioners. The manual guided designers in the selection of rocks, placements of stones, and how to perfect raked patterns.

Kyoto’s Japanese Rock Gardens

Kyoto remains home to the world’s best Zen gardens, as the phenomenon began in the city’s Zen Buddhist temples. Today it’s still possible to visit these places of quiet contemplation.

Ryoan-ji

Photo: Stock Photos from cowardlion/Shutterstock

Considered one of the world’s most beautiful gardens, Ryoan-ji is the pinnacle of Zen garden design. The garden is a 2,670-square-foot rectangle filled with white sand and 15 stones arranged in five groups of three. A trace of moss around each stone is the only sign of vegetation and each day monks carefully rake the sand into perfect patterns.

“The garden at Ryōan-ji does not symbolize anything, or more precisely, to avoid any misunderstanding, the garden of Ryōan-ji does not symbolize, nor does it have the value of reproducing a natural beauty that one can find in the real or mythical world,” wrote garden historian Gunter Nitschke. “I consider it to be an abstract composition of “natural” objects in space, a composition whose function is to incite meditation.”

Tenryu-ji

Photo: Stock Photos from javarman/Shutterstock

This garden, which was built in the 14th century, shows a transition into the dry landscape we associate with Zen gardens. A reflecting pond in the background is contrasted with a waterfall made from stone and boulders, as well as raked gravel meant to be gazed at from a viewing platform.

Saiho-ji

Photo: Ivanoff~commonswiki (CC BY-SA 3.0), via Wikimedia Commons

This example of early Zen garden design is notable for its mossy appearance. In fact, Saiho-ji is sometimes called the Moss Temple. However, this 14th-century garden didn’t always appear this way. After the temple fell into disuse, the moss slowly crept over the rocks and gravel. Still, it’s possible to see the garden’s rock islands which represent a turtle swimming in a moss lake, a meditation rock to promote calm and silence, and a dry waterfall.

Daitoku-ji

Photo: Ivanoff~commonswiki (CC BY-SA 3.0), via Wikimedia Commons

This walled temple complex actually holds 22 sub-temples, many of which feature memorable Zen gardens. In particular, the rock garden at Daisen-in is heralded for its beautiful arrangement. Scholars believe that it may be a metaphor for a journey through life. It begins with a stone waterfall, symbolizing birth, and ends with a raked symbolic river flowing into the open “ocean,” symbolizing death.

Ginkaku-ji

Photo: Stock Photos from Thomas_HB/Shutterstock

Also known as the Silver Pavilion, Ginkaku-ji is known for its incredible landscaping. Carried about by Japanese painter and landscape artist Sōami, Ginkaku-ji differs from other temples in that it was constructed as a shogun’s retreat, rather than for use by monks—it was converted into a temple after his death. A highlight is the temple’s raked sand gardens and cones, one of which is 6.5 feet tall. This cone, in particular, is thought to symbolize Mount Fuji.

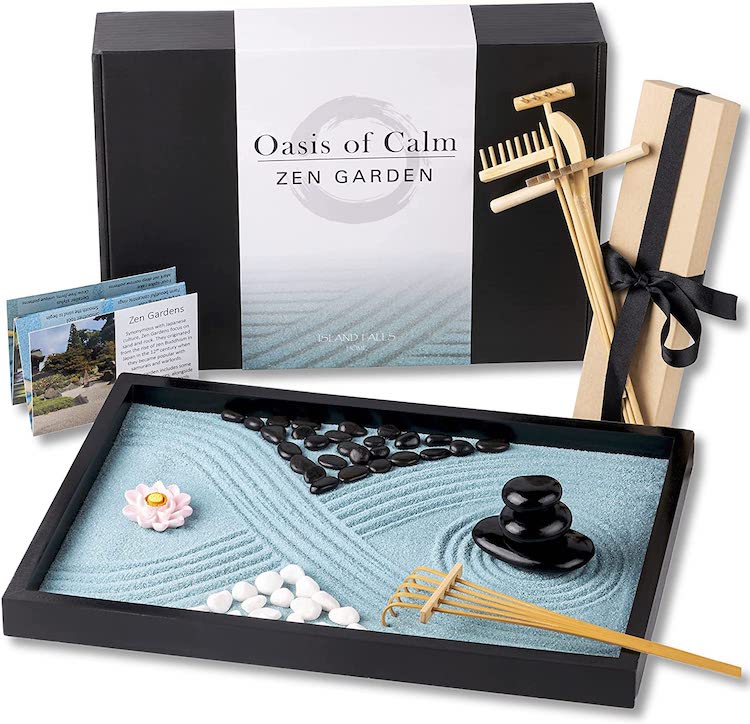

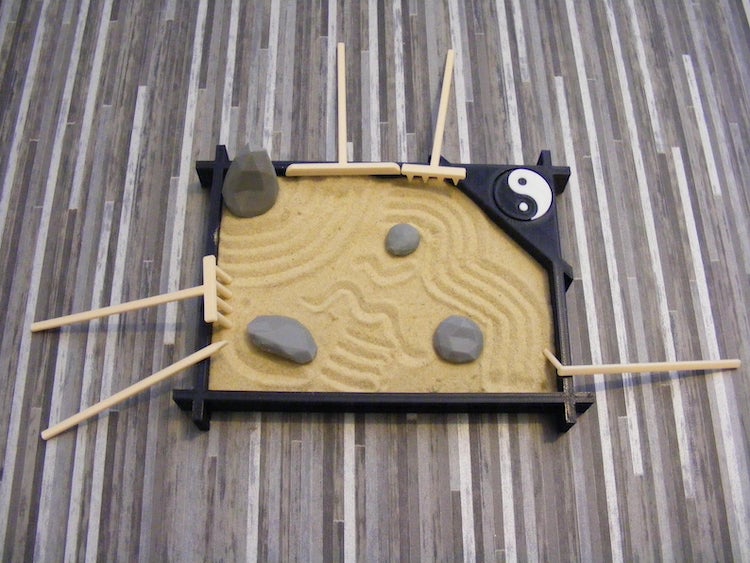

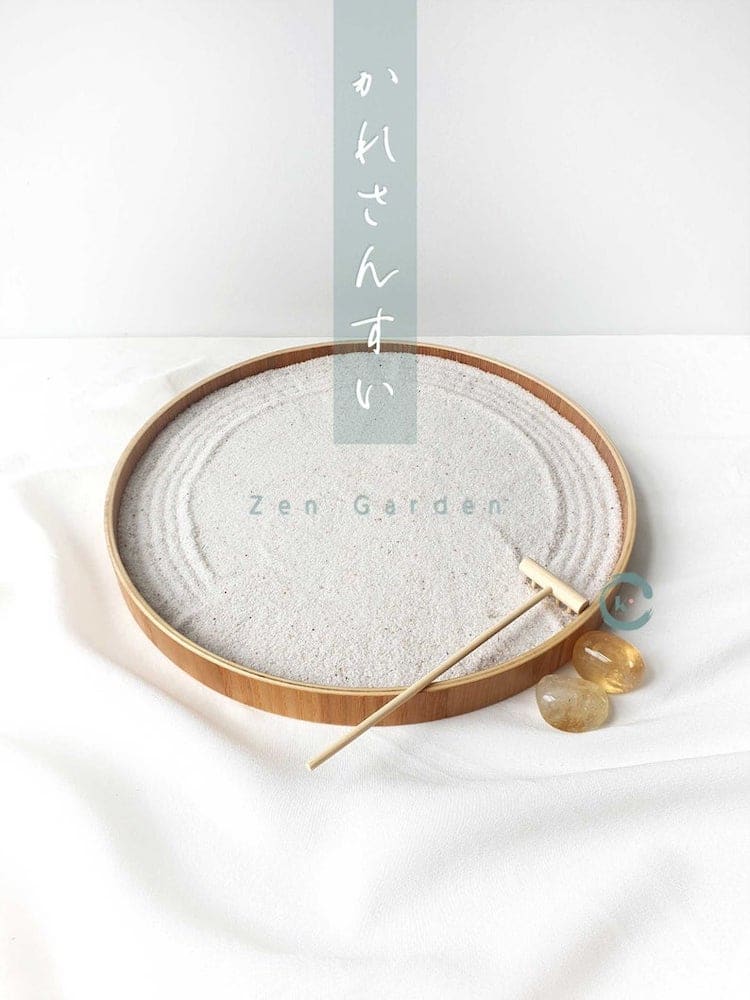

Want your own zen garden? Here are some miniature kits that help you feel zen at home.

MyZenHorizon | $19.99

Island Falls Home Store | $39.97+

Mellsva | $24.91

SandscapeDE | $49.81

ENSO SENSORY | $45.99

GeekTastic55 | $31.45

Island Falls Home Store | $39.97

Kikiskistudio | $25.94

Want to learn more? Pick up Japanese Zen Gardens by Yoko Kawaguchi or take an expert-led tour of Kyoto’s gardens.

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

Ikebana: The Art of Japanese Flower Arranging and How to Make Your Own

Wabi-Sabi: The Japanese Art of Finding Beauty in Imperfect Ceramics

Kintsugi: The Centuries-Old Art of Repairing Broken Pottery with Gold

How to Make Your Own Woodblock Print Like the Japanese Masters