Abraham Lincoln

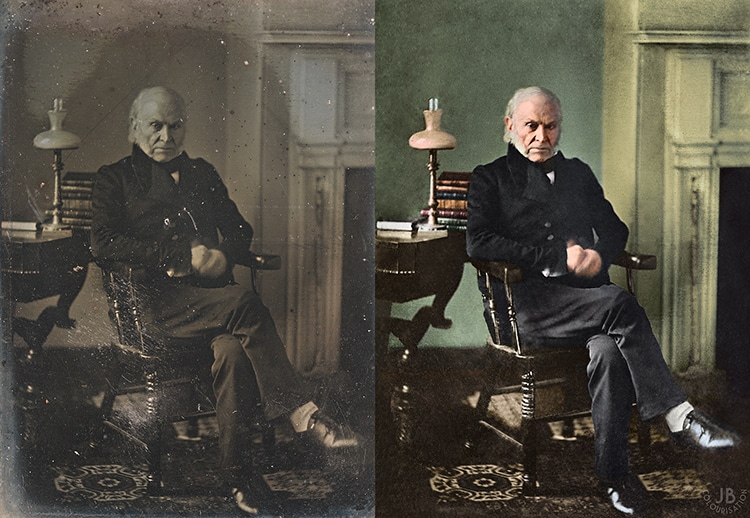

Photography changed the way people see the world, as well as the way history is remembered. In 1839, the first commercially available photographic process—the daguerreotype—was released. The sixth president of the United States, John Quincy Adams, was the first to be photographed using this process. Taken around 1843—after Adams had left office—the portrait is one of 26 black and white photographs depicting presidents who held office before color photography existed. UK-based photo restorer and colorist James Berridge made it his mission to colorize these monochromatic images. His ambitious quest brings American presidential history to life in a new, approachable way.

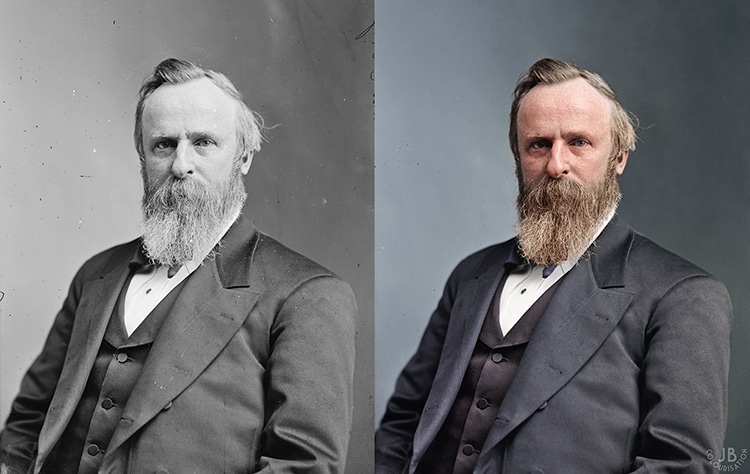

Berridge’s project began when he received a request to restore and enhance an image of Abraham Lincoln. Originally trained in video post-production, the colorist had restored historical photographs for several years. He was surprised at the reaction to the colorized portrait of Lincoln; viewers were blown away by the lifelike “reality” of a president who lived a century and a half ago. Inspired by this visceral connection to a historic figure, Berridge set out on a project to restore and colorize a photograph of each president whose image was only captured in black and white. In total, he completed 26 photographs in over 100 hours of Photoshop manipulation.

Among the presidents, Andrew Jackson was a particularly difficult restoration project. Only two photographs exist of the man, and the best daguerreotype for the project was heavily scratched and worn. To accurately restore Jackson’s features, Berridge had to draw upon the details of an engraving which had been drawn from the original image. By contrast, the colorized portrait of Theodore Roosevelt drew upon a largely intact image. Interestingly, one restoration may or may not even be of a president. In 1845, when James K. Polk was supposed to be inaugurated, he refused to take the Oath of Office on the designated date because it conflicted with the Sabbath. As a result, the Senator David Rice Atchison may technically have been President Pro Tempore by default for less than 24 hours. To be safe, Berridge included him in his project.

Berridge describes his colorization process as time-consuming but meditative. Using public domain scans of photographic prints or negatives, he begins by cleaning up each image. He erases dust specks and scratches to restore clarity by using the healing brush tool of Photoshop. Contrast is also adjusted to draw out the small details which make each president lifelike. Lastly, using the mask feature, Berridge adds color to the image. All items require base tones, mid-tones, and shadows. Skin tones require casts and undertones. Colorization is an art, and curious viewers can watch the hypnotic process in Berridge’s YouTube videos. The final step is to test the image’s appearance on different kinds of screens, to ensure the president looks lifelike to all those who will encounter his image. The good, the bad, and the ugly—the American presidents come alive in color.

My Modern Met was fortunate enough to speak with James Berridge about his stunningly colorized presidential portraits. Scroll down for our exclusive interview.

David Rice Atchison, potentially a former President Pro Tempore

William Howard Taft

You have been restoring and colorizing historical photographs for about two years now. How did you first take an interest in this type of work?

For me, it was really Marina Amaral’s amazing colorization work which first convinced me of its merits as an art form. I, along with many others, found myself staring at photographic portraits which were over 150 years old but which now looked as if they could have been taken yesterday.

I have a background in creative work, particularly visual effects and compositing and I could appreciate the level of skill, both creative and technical, needed to complete colorizations successfully. More importantly I could see that despite my previous creative experience, I didn’t have the slightest clue how to actually produce a colorized picture myself. I think it was this newly found respect for the craft, and wanting to learn how to perform it myself, which really got me interested in colorization.

Theodore Roosevelt

John Quincy Adams

What sort of historical research predates working on an image?

Well, I start with researching to see if primary sources of color information still exist. I therefore look for objects from the photographs which still survive into the modern era. Museums archives are invaluable for referencing items such as military uniforms and historical packaging.

I then dive into secondary sources such as paintings, diaries, and newspaper reports from the time. It was these types of methods I usually used for establishing the presidential eye colors and skin tones. While the public’s exposure to events may have been limited to black and white engravings or photographs, they still had a really strong interest in what color things were in real life. So you’ll sometimes find, quite literally, colorful descriptions of what the press were reporting.

These eyewitness methods can potentially be unreliable, however, as they may have been filtered through tastes and biases from the time. For example, the silent movie actress Colleen Moore had heterochromia with one of her eyes being brown and the other blue. Although the press often did what it could to hide this, so painted magazine covers from the time show her with two brown eyes. So it’s always important to look for multiple sources when possible.

Finally, if I can’t find any research sources for a particular element, I do what I can to just find similar sources from the same era. Quite often it will be impossible to find an exact vase or rug which appeared in a photograph, but other examples from the same time period still exist to be referenced and that way at least the color palette will be era authentic.

James Buchanan

What is the most challenging aspect of colorizing a black and white photograph?

It’s probably, at least for me, that a picture really doesn’t start to come together as a cohesive whole until you’re maybe 90% finished in terms of process? I’ve worked on pictures before for potentially 16-17 hours, for the bigger images, without knowing if the picture will actually look good when I’ve finished working on it.

This tends to weigh quite heavily on the process, making me constantly question if I should abandon working on a particular image while it still looks terrible. Although it has certainly become less of an issue as I’ve gained more experience, as I’m now aware this is part of the process. However, even now I don’t feel completely at ease with a picture until those final stages have been reached.

William McKinley

Andrew Jackson

For the photograph of Andrew Jackson—one of the few that exists—you had to do some extensive “damage control” by pairing the photo with an engraving done from the image. How was this process different from a standard restoration?

Well, my usual restoration process is to try and use non-damaged parts of an image to repair the damaged parts. In the case of that Andrew Jackson photograph, it was just too damaged for that process of sampling to be effective.

The biggest change in process was for me to finally start viewing the Andrew Jackson photograph as a case of reconstructing his likeness more than restoring his photograph. I did everything I could to match my reconstructed image to the original photograph, but I think sometimes accepting the limitations you face creatively does a lot to help you move forwards with projects.

I think I’ll always view this Andrew Jackson colorization as a bad restoration in the traditional sense, but in terms of showing what he actually looked like in real life, I’m quite proud of my work.

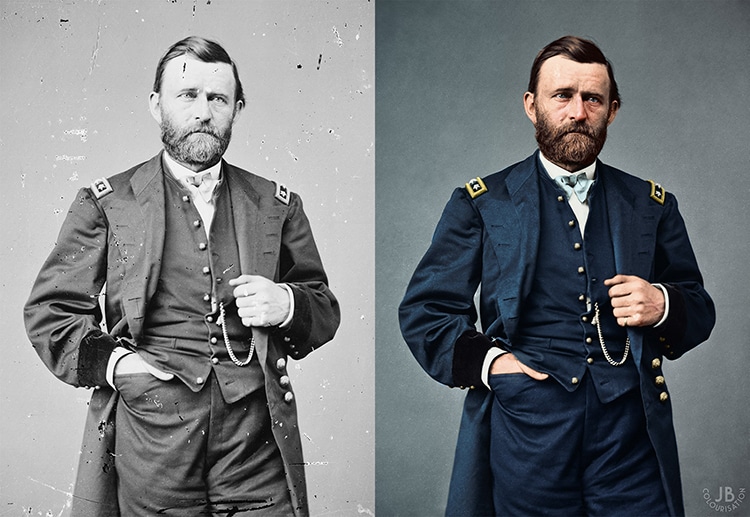

Ulysses S. Grant

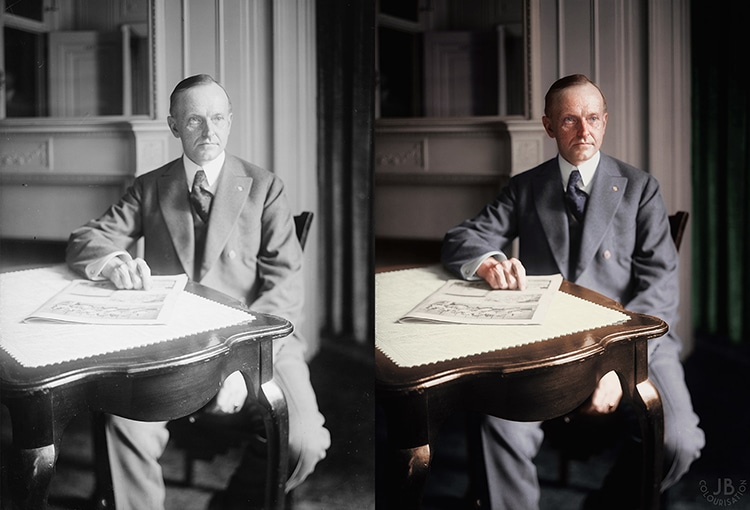

Calvin Coolidge

Hand-tinted or hand-colored photographs were popular in the late 19th century. How do you see your modern digital methods in relation to historical colorization? Did you discover any hand-tinted images of the presidents?

I’m always in awe of what people were able to do via hand-tinted colorizations during that period. I think a lot of the work from that time, particularly the images from Japan, still holds up well today. I feel that the existence of hand tinting in the past shows that color photographs were popular but potentially not an affordable option for a lot of people. So the blanket concept that every single last black and white photograph was black and white purely from creative choice is unlikely to be true.

It’s nice to feel that I and others doing digital colorization are somewhat reviving a lost art form. I think sadly that the attempts in the 1980s to cheaply color film classics like Casablanca, with predictably poor results, did a lot to damage colorization as a concept.

In terms of the presidents, I saw quite a few hand-tinted engravings but I don’t think I saw any tinted photographic images. Generally speaking I don’t tend to use them for research because you’ll sometimes find the same exact engraving colored in multiple different styles. I do, however, sometimes find old photographs which have colorization notes written on the back from the photographic session, documenting the original colors. Unfortunately that wasn’t the case with any of my Presidents I worked on or that would have been very helpful!

The damaged photograph of Andrew Jackson

(left), and an etching made from the image which was also used to create the colorized and restored portrait.

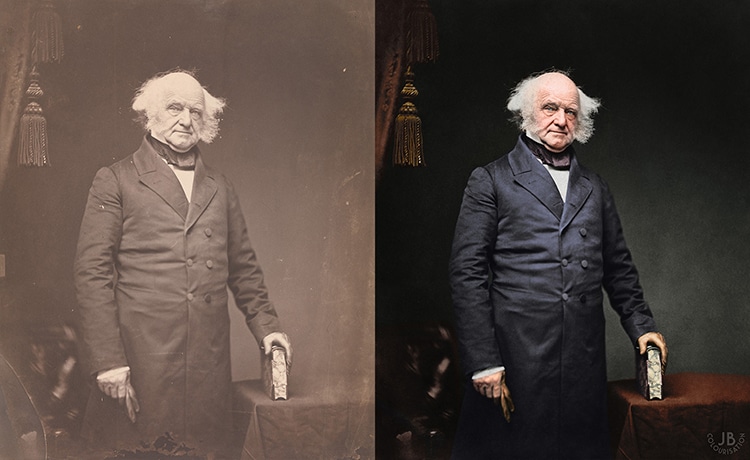

Martin Van Buren

You’ve mentioned that the colorized images of the president made viewers connect with the humanity of the past. Whether a controversial figure or a popular hero, photographs in color can bring the past to life. Can you elaborate on the historical value which you see in projects of image colorization?

I think it’s hard to connect people with the past unless you can help them empathize with those who came before us. Movies have always done a fantastic job of this, as do things like historical re-enactments. As much as I may regret professionally saying this, I think the 1997 Titanic film has done more to educate the public as a whole about that disaster than any book or documentary on the subject could ever hope to achieve. It did that singularly by making you care about the people on the ship and by also making you understand, even if only in a very small way, some of the horrifying experience that they had to face. Obviously there is always some creative license with films such as these; but, I think in terms of firing up the public’s imagination, they are incredibly useful.

A colorization allows the audience to look at a historical figure as they may have looked during their lifetime. When you can see red in someone’s cheeks, or nicotine stains in their beard, it makes them alive again.

In a way, I think colorization is a perfect way to get people engaged with history during the age of the internet swipe. Quickly swiping through images is basically how we explore the world today and for the most part we don’t tend to focus on any of those images for very long. The wonderful thing about colorizations is that they make you stop when you see one on your timeline; they make you engage with the image. You want to know who is in the picture and why they’re considered important enough to be worth coloring?

I think a lot of people feel that those who colorize photographs are trying to improve that photograph in some way. And in my experience that really isn’t true. A lot of people initially get into colorization because they want to see their loved ones as they once remembered them, or they want to be able to help their grandchildren appreciate their family history. We’re not trying to improve photographs, we’re trying to improve connections; either to the past or the future.

Scroll on for videos which show every American president in color, as well as Berridge’s process to create these colorized presidential portraits.

Rutherford B. Hayes

Watch the presidents in historical order.

Was David Rice Atchison ever a U.S. President?

Watch as Berridge introduces his process.

James Berridge: YouTube | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter

My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by James Berridge.

Related Articles:

History Comes to Life Through Beautiful Colorized Photographs

Artificial Intelligence Revitalizes 1902 Footage of a “Flying Train” Ride Through a German Town

Colorized Photos Breathe New Life Into Famous Faces From History

Colorized Portraits of Ellis Island Immigrants From 100 Years Ago