Photo: Stock Photos from STUNNINGART/Shutterstock

Americans—and much of the wider world—are watching the continued counting of votes from Tuesday’s election. However, what many people do not know is that votes are still being counted days after the election in most “normal” years—those without pandemics or large-scale mail-in voting. This is a normal process that usually goes unnoticed because the complicated election math of statisticians allows the media to call a race on election night. This year, the process of tabulating votes may seem frustratingly slow, but as many election officials have stressed—it is important to get the count right. But how are votes actually counted?

The American electoral system is quite decentralized with different states (and counties) having diverse policies for voting, tabulating, and reporting. However, understanding the basics which hold true in most localities can shed light on what happens to your vote once it enters the electoral system. To start, different kinds of ballots take different processing paths.

If a citizen votes in person—either early or on election day—poll workers verify the identity of the voter before they cast their ballot on paper or through an electronic voting machine. Poll workers hail from both major parties and work in teams to ensure objectivity. In certain locations, votes cast in person may be electronically tabulated at the polling location. As voters or poll workers deposit completed ballots through electronic optical scan tabulators, votes are registered on a memory card. The physical ballots are stored in secure boxes. In other locations, the physical ballots may be securely collected (but not yet scanned) until the polls close. When voting is closed, the physical ballots and any digital voting records are usually transported securely to central county tabulation centers. The county totals begin to aggregate.

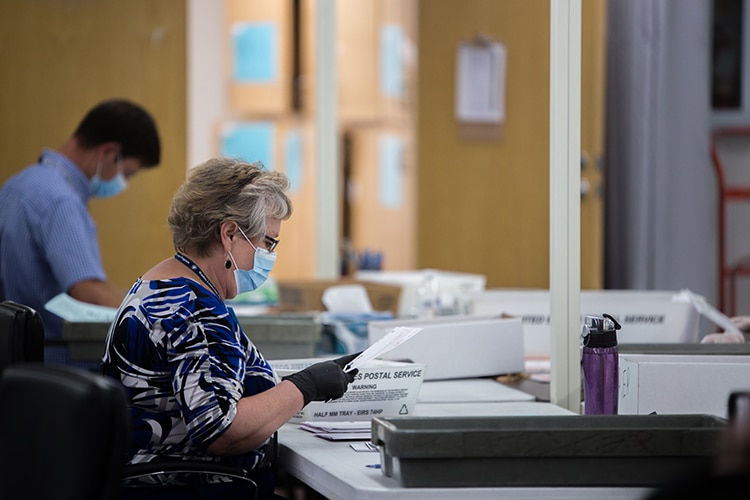

Other votes arrive by absentee or mail-in ballots—sent through the mail or delivered to drop-off locations. These ballots must go through an extra step before tabulation: verification. Bi-partisan election workers verify the signatures on envelopes and record who is casting their votes. This is much like what is done when in-person voters check in before receiving their ballot. Verified ballots are then prepared for tabulation, which is done either by hand or by optical scanning machines. Once tabulated, these votes join the county totals. Due to COVID-19, the number of mail-in ballots this year is unprecedented. However, this way of voting was already gaining in popularity before the pandemic. The present wait for election results is not due to late-arriving ballots, but rather to the time-consuming process of opening envelopes, verifying signatures, flattening creased ballots, and finally counting those votes. Some states, such as Pennsylvania, prohibited this lengthy process from beginning before election day. (You can see inside the tabulation centers of Pennsylvania on CNN.)

Counting both in-person and mail-in ballots, counties report additions to their totals to their respective states. As anyone watching the returns come in knows, the pace of this process is determined by state laws, election staffing, and technical capacities, among other unpredictable factors. Poll watchers, or election observers, can be present during tabulation. In most states, there is no automatic right to observe the polls. Usually, political parties must nominate their observers in advance of the election, and, in some states, training is required for those nominated. Other observers are non-partisan; like the bi-partisan teams of poll workers, they are there to ensure a fair election and counting of the votes. In the era of modern media, many Americans can also see inside the counting facilities through their televisions and Twitter feeds. In Arizona, for example, every vote tabulation center must have a public live video feed.

The work of counting American votes is always a long process. Provisional ballots must go through extra verification steps, while ballots with issues may be cured—i.e. fixed by the voter. For this reason, many states have two full weeks to prepare their official vote count report—a process known as a canvassing. These results must be certified by the state’s top election officials before being sent to Congress. The results also impact the allotment of Electoral College votes. If a candidate demands a recount—or one is automatically indicated by a state law due to a close vote count—the process of counting votes may be repeated.

To learn more about voting rights and laws in America, visit Vote.org or your state election website. If you believe your ballot has been wrongly rejected, visit your state and county election websites for information and deadlines on curing your ballot.

People today appear to be more intrigued by the voting process in the United States, given the length of the current election.

Photo: Stock Photos from TREVOR BEXON/Shutterstock

To learn more about the entire journey of your vote—from casting to counting—check out this helpful video from Liz Scheltens of Vox.

Related Articles:

TIME Magazine Replaces Its Cover Logo for the First Time Ever With One Word: VOTE

Astronauts Can Vote From Space, You Can Vote From Earth

Mattel Introduces a Susan B. Anthony Barbie to Celebrate Women Voters