Hazel Scott making a guest appearance at the Naval Training Station in Great Lakes, Ill., in December 1943. (Photo: National Museum of the U.S. Navy, Public domain)

On July 3, 1950, Hazel Scott became the first Black performer to host her own television show in the United States. Eponymously titled The Hazel Scott Show, the program showcased Scott’s tremendous talent as a pianist, premiering with strong ratings and stellar reviews. But decades before her TV show, Scott had already proven herself a pioneer within the Black music scene and beyond.

Born on June 11, 1920, in Port-au-Spain, Trinidad, and subsequently raised in Harlem, Scott was introduced to the piano at a young age by her mother, Alma Long Scott, who was also a trained pianist and self-taught jazz saxophonist. By the age of eight, Scott auditioned for the prestigious Juilliard School of Music despite its strict minimum age requirement of 16, playing Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in C-Sharp minor for director Frank Damrosch. Awed by her skills, Damrosch ultimately made an exception for Scott, offering her a scholarship and private lessons with Professor Oscar Wagner.

It didn’t take long for others to recognize Scott as a musical prodigy as well. As a teenager, she played her first formal concert in New York; hosted her own radio show on WOR; served as an intermission pianist for Frances Faye at the Yacht Club on 52nd St.; and was cast in her first Broadway musical, Sing Out the News, in 1938. In 1939, these early successes culminated at Café Society, New York’s first fully-integrated nightclub and one of the city’s hottest jazz venues. When close family friend and jazz legend Billie Holiday ended her standing engagement at the club three weeks early, she insisted that Scott replace her. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Scott’s incredible command over the piano and her magnetic presence captivated audiences, and she quickly became the club’s premiere headliner, cleverly reimagining classical pieces through jazz improvisation. TIME Magazine even heralded her as the “hot classicist.”

A year later, in 1940, Café Society opened an uptown location on 58th St., with Scott maintaining top billing. That same year, she recorded her first solo album for Decca Records, Swinging the Classics, which encompassed her Café Society repertoire. Throughout the 1940s, she traveled the world with her Bach to Boogie recordings, armed with a contract that stipulated she would only perform for integrated—not segregated—audiences. “Why would anyone come to hear me, a Negro, and refuse to sit beside someone just like me?” she once remarked.

Scott eventually brought her talents to Hollywood, where she starred as herself in such films as Something to Shout About, I Dood It, and Rhapsody in Blue. Here, too, she maintained strict contractual conditions: she would never wear a maid’s uniform, nor would she play a subservient character of any kind, defying Black stereotypes typical of that era. It was also around this time that she married Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., who, in 1944, became the first Black American elected to Congress from New York.

Together, Scott and Powell fought for Black empowerment, justice, and liberation in their respective fields. When she launched The Hazel Scott Show in 1950, performing alongside musicians like Charles Mingus and Max Roach, Scott had solidified herself not only as one of the country’s biggest faces in entertainment but also as one of the most staunch advocates for civil rights and social progress. After all, she had led an actors’ strike when a film director sought to dress his Black actors in dirty costumes and sued a restaurant when it refused to serve her due to her race.

This advocacy, however, placed a target on Scott’s back during the McCarthy Era. Once she was named in Red Channels and CounterAttack, two right-wing journals that cataloged suspected communists in film, TV, and radio, Scott demanded to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), set for September 1950. In terms of The Hazel Scott Show, which debuted earlier that summer, her timing was inopportune—her HUAC backfired, and her show was cancelled. No longer employable in the U.S., she left for Paris, where a Black expatriate community was already flourishing.

In 1967, Scott finally returned to the U.S., but its musical landscape had already moved on. Still, she continued to perform and record for smaller audiences before her untimely death from pancreatic cancer on October 2, 1981.

Forty-five years after her death, Scott remains a steadfast symbol of Black excellence, someone who transformed her art into activism during an age of intense marginalization and inequality. “I think America is as big and as strong as its weakest point,” she once said. “It is up to a Negro to be the conscience of this great land of ours.”

In 1950, piano prodigy Hazel Scott was the first Black performer to host her own TV show in the United States.

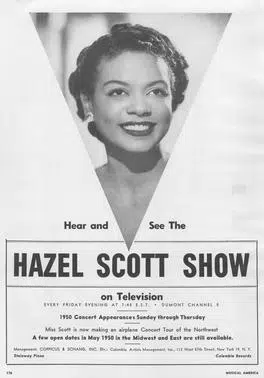

Advertisement for ‘The Hazel Scott Show,’ 1950. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Even before her TV debut, Scott was a staunch advocate for civil rights in entertainment, refusing to perform for segregated audiences.

Hazel Scott in October 1947. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Across her incredible career, Scott revolutionized classical music, cleverly reimagining it through the lens of jazz improvisation.

Sources: Looking Back at the Extraordinary Life of Hazel Scott; National Women’s History Museum: Hazel Scott Biography; The Disappearance of Miss Scott; Hazel Scott biography and career timeline; Hazel Scott was a force for Black experimental music; Hazel Scott, 61, Jazz Pianist, Acted In Films, On Broadway; Say it Loud: Black, Immigrant & Proud

Related Articles:

“Superfine” Exhibition Explores Intertwined History of Black Identity and Style

New Exhibition Contends With Black Heritage Through Layered, Evocative Textile Art