Photo: Rawpixel.com / Shutterstock

One often associates graffiti with vandalism, but over the past 40 years, graffiti art has proved to be much more than kids writing on walls. From its start as a New York subculture to the international explosion of street art, graffiti has slowly invaded contemporary culture.

We take a look at 10 key moments in the history of graffiti art that helped push the art form into mainstream culture, from Keith Haring’s Pop Shop to Bart Simpson turning into a graffiti writer.

Photo: Wikipedia

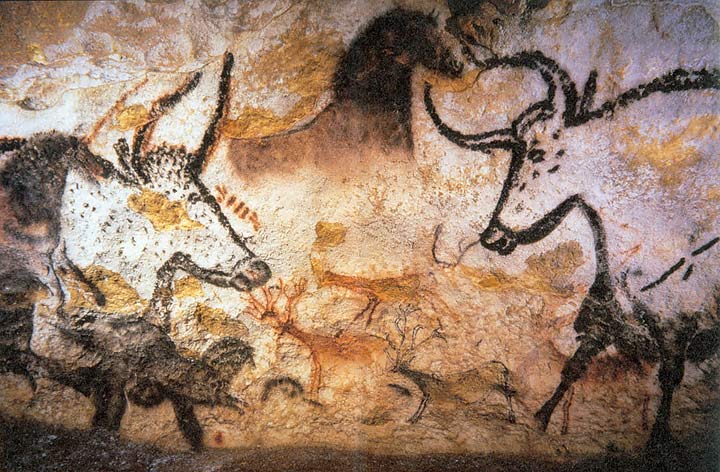

Prehistoric Cave Paintings Prove that Writing on the Walls Isn’t New

In 1940, a group of French teenagers stumbled upon paintings inside the Lascaux Caves in southwestern France. The rudimentary drawings of animals, human figures, and abstract signs drawn on the walls of the caves go back to 17,000 BP, proving that man has always found the need to express himself publicly. The tradition doesn’t end here. Graffiti in the Italian archeological site of Pompeii, dating back to 78 B.C., reads “Gaius Pumidius Diphilus was here.”

Photo: TAKI 183

Graffiti Featured in The New York Times

In 1971, the New York Times published an article about then-teenage graffiti artist TAKI 183. The article was groundbreaking. A mainstream publication was, for the first time, not only discussing graffiti but speaking with an artist and getting insight into why they do what they do. It also spawned more graffiti artists in New York City, which would become the hotbed of activity that would influence graffiti art around the world.

Photo: Martha Cooper

Martha Cooper Meets Dondi

Legendary graffiti and street photographer Martha Cooper first entered the New York graffiti scene in the 1970s, after seeing a boy named Edwin writing on a wall and asking him what he was doing. This led to an introduction between Cooper and Dondi, one of the most important graffiti art practitioners of his generation. He allowed Cooper unprecedented access inside his world, letting her follow along and document graffiti in action. These images, along with those by Henry Chalfant, would be published in Subway Art, which is known as the Holy Grail of graffiti subculture documentation.

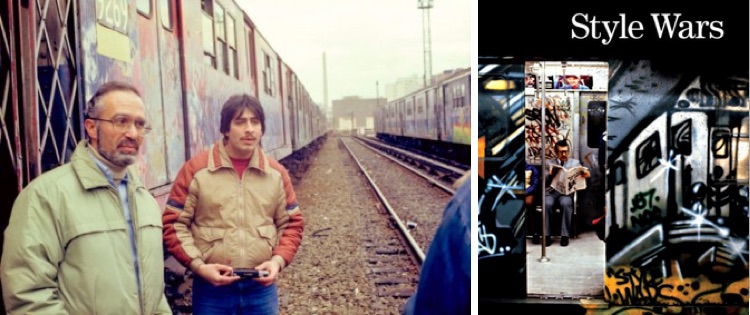

Left: Director Tony Silver and artist Seen in 1982. Right: Style Wars poster. (Photos: Night Flight)

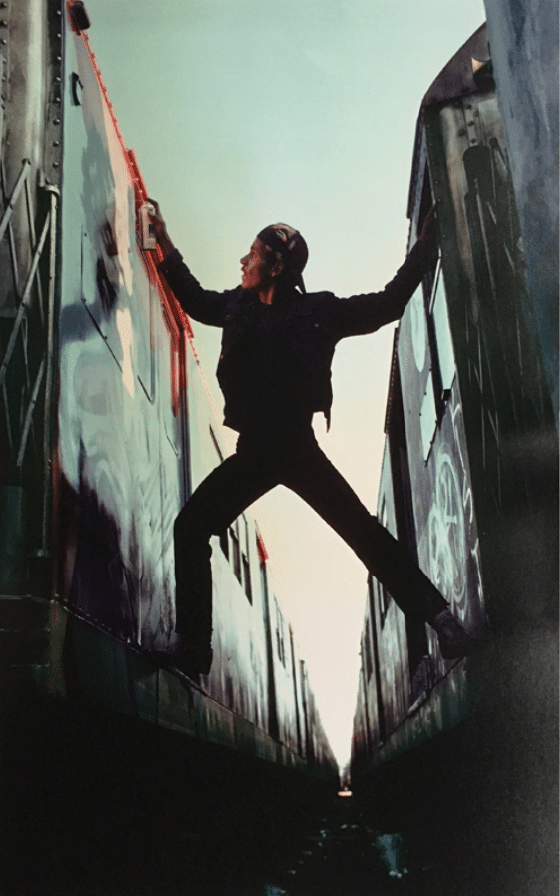

Style Wars Documentary Released

In 1983, director Tony Silver, in collaboration with photographer Henry Chalfant, released Style Wars. Originally airing on PBS, it exposed New York’s hip hop and graffiti culture to a wider audience. By showing not only the artists, but also law enforcement officials and politicians, it also opened up the debate about vandalism versus artistic expression. In 2009, A.O. Scott wrote the following about the film in the New York Times, “Style Wars is a work of art in its own right too, because it doesn’t just record what these artists are doing, it somehow absorbs their spirit and manages to communicate it across the decades so that we can find ourselves, so many years later, in the city, understanding what made it beautiful.”

In 2009, A.O. Scott wrote the following about the film in the New York Times, “Style Wars is a work of art in its own right too, because it doesn’t just record what these artists are doing, it somehow absorbs their spirit and manages to communicate it across the decades so that we can find ourselves, so many years later, in the city, understanding what made it beautiful.”

Left: Basquiat in 1981 (Photo: Rex Features) / Right: Andy Warhol and Basquiat in 1985. (Photo: Michael Halsband)

The Rise of Basquiat

Jean-Michel Basquiat was a Brooklyn-born artist whose ascent into the contemporary art world heralded a new era for graffiti artists by proving that they could make the leap into the mainstream art world. Basquiat first gained notoriety in the 70s for his tag SAMO, which is spread across Lower Manhattan with his friend Al Diaz. In 1978 The Village Voice published an article about their work, but by the following year, the project was over. The duo scrawled SAMO IS DEAD across SoHo to signify the end of the era.

By that time, Basquiat was already making waves in high-end circles, and into the early 80s he continued gaining success as a solo artist, collaborating with David Bowie and Andy Warhol, as well as exhibiting at the legendary Gagosian Gallery. His rise would be an early precursor of the mainstream success that many graffiti and street artists enjoy today.

Photo: The Keith Haring Foundation

Keith Haring Opens the Pop Shop

Gaining notoriety with his artwork in the New York subways in the 1980s, Haring quickly rose to fame. From 1984 he received international commissions, flying around the world to create highly visible public art—a model that street artists emulate today. But it was the opening of his Pop Shop in downtown Manhattan in 1986 that would help prove the commercial viability of graffiti art. Haring realized the importance of making his art available to the masses and for twenty-two years the store sold everything from clothing to gift items adorned with Haring’s signature style.

Photo: Obey Giant

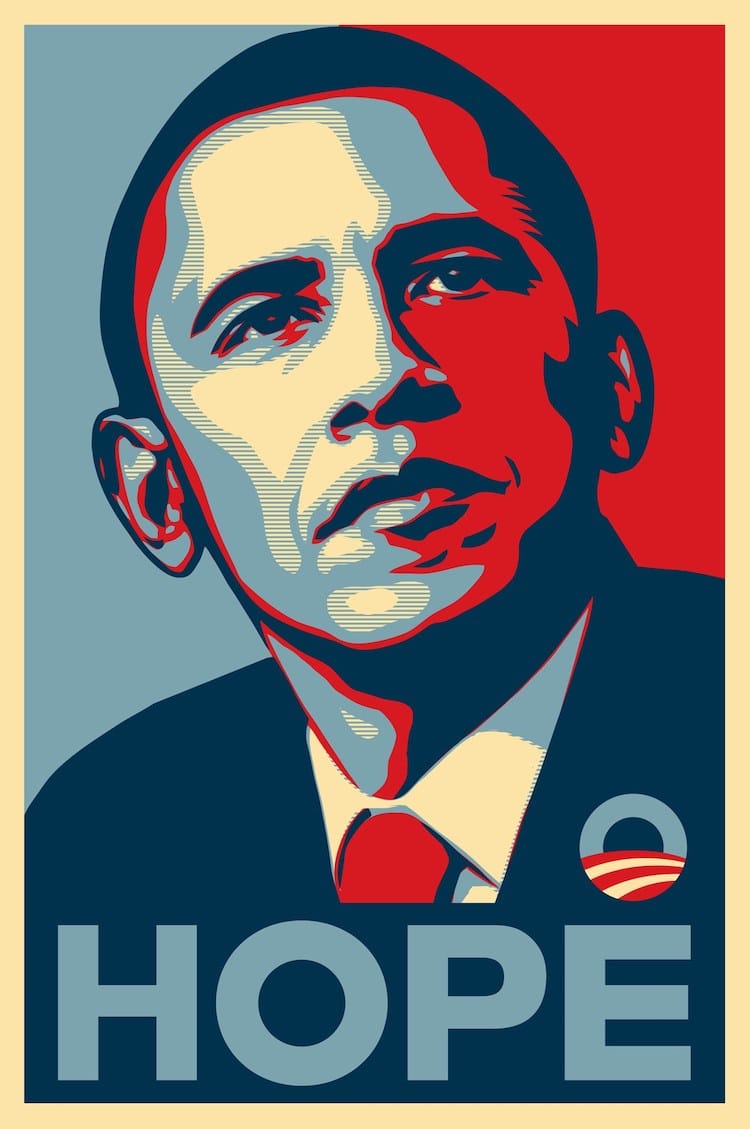

Shepard Fairey’s ‘Hope’ Poster Becomes the Symbol of the 2008 Presidential Election

What started as an independent tribute to the presidential campaign of then-Senator Barrack Obama, transformed into the icon of the 2008 U.S. presidential election. Shepard Fairey, already enjoying a successful career, became a household name with this poster, which was designed in one day. After being officially adopted by the Obama campaign, it became the symbol of the election and spawned many variations and imitations. You can now find it on a wide variety of items, from T-shirts to coffee mugs.

Work by Barry McGee, AKA Twist.

Graffiti and Street Art Hit the Museum

The Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles’ 2011 exhibit Art in the Streets, certainly wasn’t the first time that graffiti art entered a museum, but it’s one of the most memorable. Under the helm of then-director Jeffrey Deitch, a champion of graffiti and street art, the show was a comprehensive look at the history of graffiti and its later development into street art.

While including street art giants like Bansky and Shepard Fairey, the exhibit gave equal space to graffiti artists like TAKI 183, Fab Five Freddy, Lee Quinones, and RISK. By some estimates, it’s the most well-attended exhibit in MOCA’s history, proving that the public is hungry for all things graffiti.

Photo: Simpsons World

Bart Simpson Becomes a Graffiti Artist

There’s nothing more mainstream than appearing on the longest-running American sitcom and animated series. And in 2012, The Simpsons dedicated an entire episode graffiti and street art. Inspired by Banksy’s 2010 film, Exit Through the Gift Shop, the fifteenth episode of the twenty-third season is titled Exit Through the Kwik-E-Mart. The episode, which features animated versions of Shepard Fairey, Ron English, and Kenny Scharf, sees Bart transform into a graffiti writer. Touching on the complex issues of art versus vandalism, Bart is offered a gallery exhibit and then arrested for painting the town.

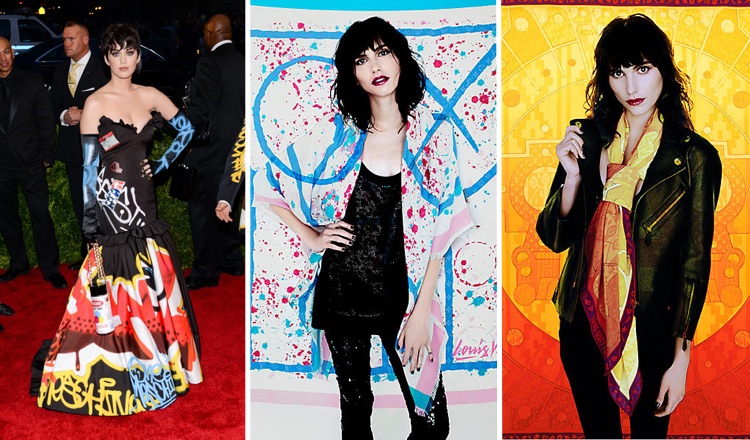

Left: Katy Perry at the 2015 MET Ball (Photo: Sky Cinema / Shutterstock) / Center and Right: Louis Vuitton Art Scarves (Photos: Louis Vuitton)

High Fashion Turns to Graffiti for Inspiration

The fashion world loves to look at subculture trends for inspiration and graffiti art is no exception. With its artist scarves collection, Louis Vuitton transformed its high luxury brand into something more accessible for the mainstream, while at the same time grabbing more of the youth market. From 2012 to 2014 they put out a series of scarves designed by graffiti and street artists such as Kenny Scharf, Stephen Sprouse, Lady AIKO, eL Seed, and Os Gemeos.

Apart from direct artist collaborations, graffiti culture has also served as a source of inspiration. In 2015, Katy Perry donned a graffiti style dress designed by Jeremy Scott for Moschino to the illustrious MET Ball. While making fashion waves, the dress was also later caught in a copyright infringement lawsuit, later settled out of court, when the graffiti artist RIME recognized his tags on the dress’s fabric. This wasn’t the first time that a fashion house had to tread lightly when using graffiti. In 2014, artists Revok, Reyes and Steel also sued Roberto Cavalli for incorporating their graffiti into a fabric for a series of Just Cavalli clothing and bags.

And so here we’ve come full circle, from being viewed as vandals who feared arrest to taking charge of the copyright of their work, graffiti artists continue to rise to the forefront of contemporary culture.

Related Articles:

10 Street Artists You Should Know

10 Stencil Artists Changing the Way We Look at the City

Senior Citizens Learn to Graffiti in Creative Workshop That Aims to Banish Ageist Stereotypes