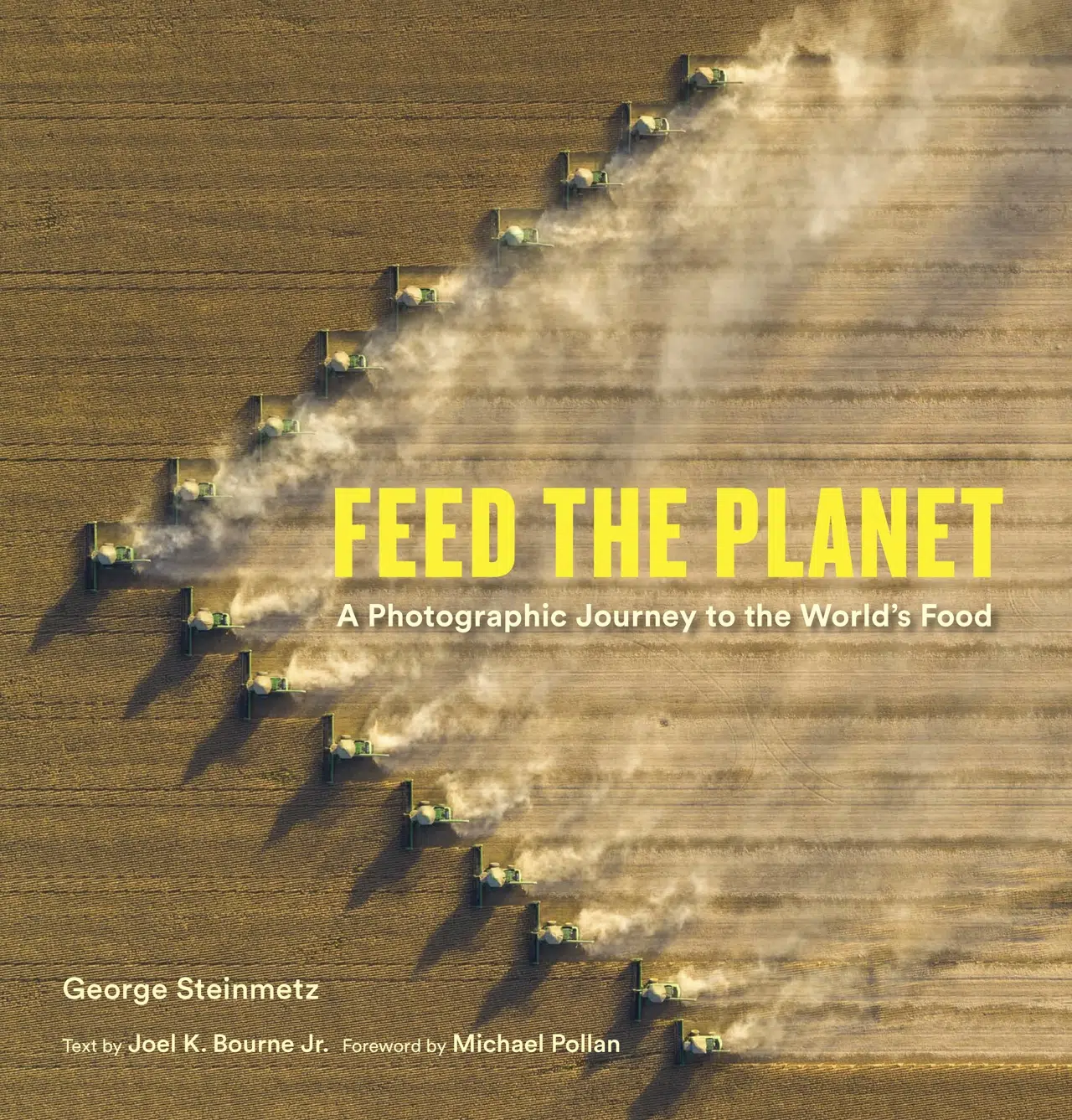

Soybean harvest, Fazenda Piratini, Bahia, Brazil.

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

For the past decade, award-winning documentary photographer George Steinmetz has been taking a look at the immense effort needed to put food on our table. With his new book Feed the Planet, we go around the world, from food processing plants in China to wheat fields in the American Midwest. Through his lens, we get an insider look at where our food really comes from.

Steinmetz, best known for his aerial photography, is a regular contributor to National Geographic and The New York Times. His long-term projects address pressing global issues, from climate change to the global food supply. For Feed the Planet, Steinmetz spent 10 years visiting 36 countries, 24 U.S. states, and five oceans. The result is a comprehensive look at the food chain in a way that most of us have never experienced.

“Most of us only come into contact with raw food in the supermarket, and are unaware of the methods used to raise it,” he writes. “In many cases, the food industry goes to significant lengths to prevent us from seeing how our food is produced. Access to this information is central to the personal decisions we make about what we eat, which cumulatively have huge environmental impact. This project seeks to show how our food is produced, so that we can make more informed decisions.”

Steinmetz’s photographs show the Herculean effort it takes to support our planet’s growing population. Using an aerial perspective, he’s able to capture the immense number of machines—or human bodies—it takes to harvest and process the food we pick off grocery store shelves.

Informative captions by veteran environmental journalist Joel K. Bourne Jr. bring Steinmetz’s images to life, providing clear explanations to accompany the powerful visuals. From traditional fishing and vegetable cultivation to wheat and rice cultivation, Steinmetz tracks the often far-afield origins of our kitchen staples. Following these items across land and sea, he brings into clear view the modern realities of the global food chain.

Feed the Planet is now available for purchase via Bookshop. Autographed copies are available via the photographer’s website.

For the past decade, award-winning documentary photographer George Steinmetz has been taking a look at the immense effort needed to put food on our table.

Mauritania was a country of pastoral nomads when it gained independence from France in 1960, but it has since become a nation of fishermen as well, with hundreds of pirogues lining the beach of the capital of Nouakchott. The official annual national landings are around 900,000 tons, but researchers who include illegal or unreported hauls put the catch at more than twice that. With many fish stocks moving north and farther offshore as sea temperatures rise, the competition for fish turned violent in 2023 in neighboring Senegal, where fishermen from the town of Kayar burned drift nets illegally set by fishermen from Mboro in the Kayar Marine Protected Area. In response, the Mboro fishermen attacked Kayar boats with gasoline bombs, killing one boy and wounding twenty others. Government intervention prevented an outright civil war between fishing groups, but tensions are endemic to communities that have grown dependent on declining natural resources. Some 600,000 Senegalese are now employed in fisheries. Fish are a primary source of protein for both Mauritania and Senegal.

Slow food is hard work at the Magazzini Generali delle Tagliate warehouse in Emilia Romagna, Italy. It’s the Fort Knox of cheese, with an inventory of 500,000 wheels worth an estimated 150 million euros. Production of classic Parmigiano Reggiano dates back to Benedictine monks in the Middle Ages. For the last eighty years, production has been strictly controlled. Cows must be raised in the provinces of Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena, and parts of Bologna and Mantua, and eat only the local forage without any silage. It takes 145 gallons of milk to make each 84-pound wheel, which is aged at least a year, being turned and brushed every seven days to cure properly. At the end of the year experts tap each wheel with a hammer to listen for defects and decide whether it is worthy to be branded with the mark of Parmigiano Reggiano. If so, it’s left to cure for another twenty-four to forty months.

Seventeen-year-old John Jorenby harvests organic peas on the massive Gunsmoke Farms, which covers some 54 square miles outside of Pierre, South Dakota. Jorenby works for Olsen Custom Farms, the largest contract harvester in the United States. The company’s fleet of million-dollar machines work ten-hour days from May to December following the ripening crops in North America’s breadbasket from Texas to Canada. Gunsmoke Farms, once owned by actor James Arness, star of the popular Western television series of that name, was bought by venture capital firm Sixth Street Partners in 2016 with plans to produce organic wheat and other crops for General Mills’ Annie’s macaroni and cheese. Poor weather, combined with excessive tillage that ignored soil conservation plans for the farm’s fragile soils, led to dust storms and severe erosion on the historic property in 2021. In 2023, the certified organic land was leased to a new manager for a mixture of organic and conventional farming.

With Feed the Planet, we go around the world, from food processing plants in China to wheat fields in the American Midwest to see where our food really comes from.

A few of the two thousand workers at the CP Group’s chicken processing plant in Jiangsu, China, prepare broilers for the domestic market, including fast-food chains like McDonald’s, KFC, and Burger King. On a typical day they process 200,000 birds and double that number prior to Chinese holidays. Thailand-based CP Group was one of the first companies to set up shop in China when it opened for foreign investment in 1979, and today runs a multinational conglomerate of poultry, swine, and animal feed operations throughout Southeast Asia. Every part of the chicken is utilized, from chicken fat, which is used in paint, to feathers that are ground into animal feed. In China, chicken organs, feet, and heads are sold for human consumption. The company aims to be the “kitchen of the world,” but outbreaks of avian flu in China, as well as numerous food safety scares, have made some countries wary of importing Chinese poultry.

From sleepy sixteenth-century village to twenty-first-century internet sensation, Sułoszowa in southern Poland (population six thousand) earned millions of online fans after this aerial image of the one-road town went viral in 2020. It was the field system of narrow strips of farmland attached to the back of each house that caught everyone’s eye. Known as a Waldhufendorf, or “forest village,” the town’s layout was common in Central Europe during the late Middle Ages, as settlers reclaimed forests in hilly or mountainous areas. Each farmer received an equal allotment of roughly 40 acres—enough for one family to farm without help from others. Although the strips have narrowed over the years as they’ve been divided and passed to each generation, they still produce wheat, oats, potatoes, cabbage, and strawberries, among other crops.

Working one shrimp at a time, women workers at Avanti Frozen Foods in Yerravaram, Andhra Pradesh, India, can de-shell and de-vein up to 44 tons of farmed shrimp per day from the company’s 1,600 acres of shrimp ponds. Avanti is one of the largest shrimp exporters in India, which dominates the global shrimp export market. About 75 percent of its frozen shrimp is exported to the United States, with Costco being one of its major customers. Shrimp is the most valuable traded marine product in the world, with an estimated market value of nearly $47 billion in 2022. More than half of that shrimp (55 percent) comes from farms instead of the sea. In 2017, researchers calculated that it took about 0.8 pounds of wild fish—converted to fish oil and fish meal mixed with plant-based food—to make 1 pound of farmed shrimp.

Modern cowboys conduct wellness checks on horseback at the Wrangler Feedyard in Tulia, Texas, the last home to around fifty thousand head. Wrangler is one of ten feedlots in Texas and Kansas owned by Amarillo-based Cactus Feeders that collectively can provide feed and care for a half million cattle. At the Wrangler facility, cattle arrive at around 750 pounds, then spend five to six months eating some 20 pounds of dry feed and fodder each day until they reach slaughter weight. Cactus sends more than a million head to slaughter each year, typically to the Tyson beef processing plants in Amarillo, Texas, and Holcomb, Kansas. According to the Texas Farm Bureau, there are more cattle on feedlots within 150 miles of Amarillo than any other area in the world. Economies of scale make concentrating large numbers of cattle in feedlots highly efficient at producing beef, as well as large amounts of waste. Giant feedlots like Wrangler boomed in the US in the 1960s and, with the use of corn feed, improved genetics, growth-hormone implants, and feed additives, increased the beef production per cow from less than 250 pounds in 1950 to more than 660 pounds today. With the help of imported cattle from Canada and Mexico, beef production in the US nearly doubled between 1960 and 2022 from roughly the same herd size.

Informative captions by veteran environmental journalist Joel K. Bourne Jr. to accompany Steinmetz’s visuals, Feed to Planet is a fascinating look at the global food chain.