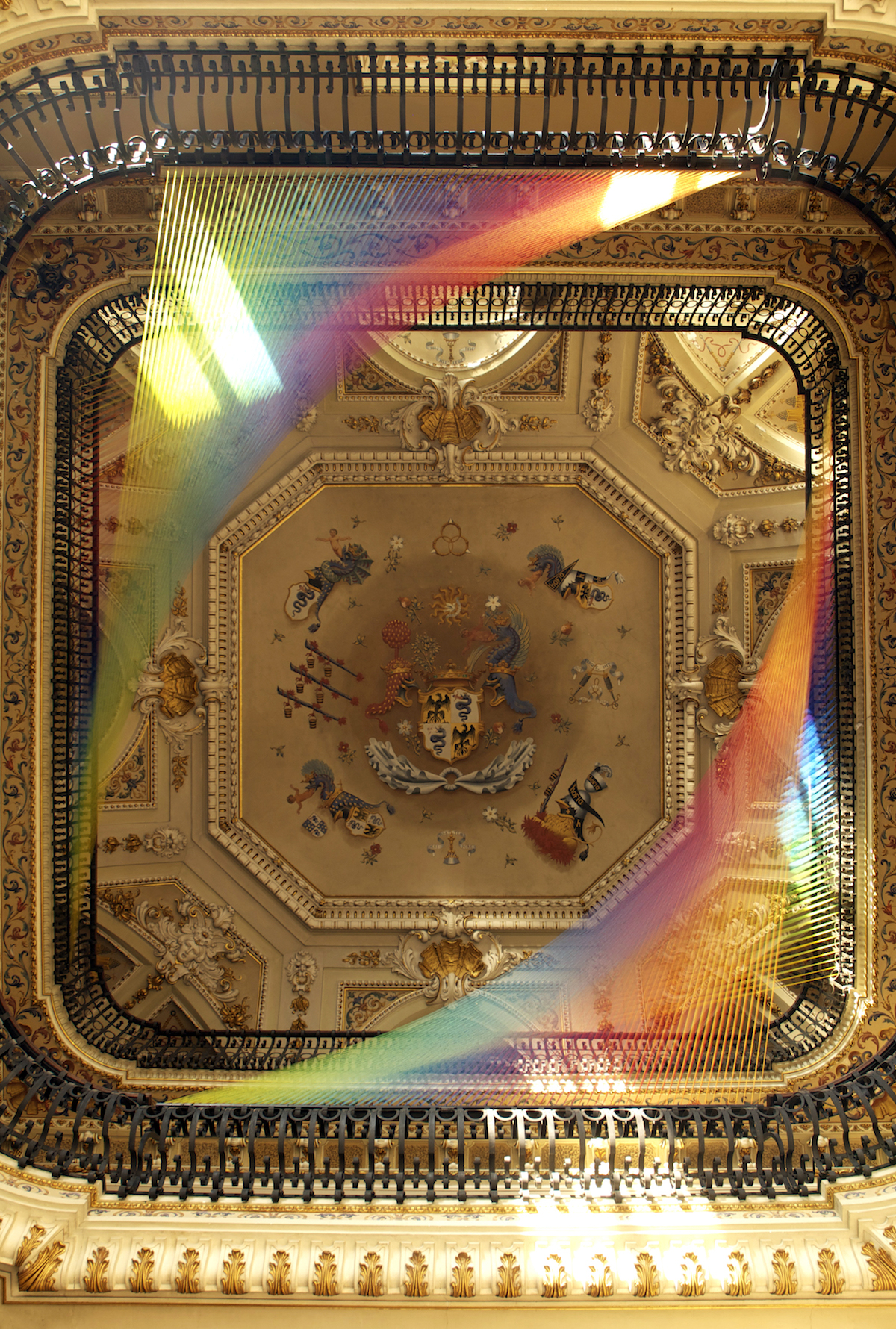

Gabriel Dawe Plexus No. 35 at the Toledo Museum of Art. Photo: Andrew Weber

Artist Gabriel Dawe creates awe-inspiring thread art that is seemingly magic. Simply put: he makes rainbows indoors. Known for delicate site-specific installations, the massive pieces span sections of art galleries—but that’s not all! His work also appears in places where anyone can see it, including airports and office buildings. No matter its locale, the stretched thread pieces conjure the same effects: they dazzle with reflected light and send even the most casual passerby into a momentary state of wonder.

Dawe’s textile art is the product of following a creative intuition that began as a way to challenge the constraints of masculinity and the patriarchy. As a child, he remembers his grandmother teaching his sister to embroider, but not him because he was a boy. In his adult years, he realized that, if he wanted, he too could acquire this skill. Learning embroidery and attending graduate school ultimately lead him to the installations that have earned him worldwide acclaim.

A rise in popularity and an enthusiastic audience response to his pieces have naturally caused his work to evolve (and grow) in meaning over the years. But throughout it all, he has not lost sight of the characteristics that are important to him. One of the most important components is color; he uses hues to help subvert the world’s narrow view of gender and identity to allow people to express who they truly are.

“A really important aspect of my work is the color,” he tells My Modern Met. “It took the installations to really give me the permission to explore with the full spectrum. I’ve always really liked really bright colors. To me, tolerance is the embodiment of joy. So, not just color but the full spectrum. I love the idea that all of these different components come together to form a unity.”

We were honored to speak with Dawe about artistic practice. Scroll down to read our interview with him, which has been edited for clarity and condensed for length.

Plexus No. 35 at the Toledo Museum of Art. Photo: Andrew Weber

Your past has really played into the artwork that you’re currently making. Can you briefly describe the influence for the installations?

It developed out my work with textiles. I don’t really have training in textiles. I never weaved and never went to school to learn the technique. When I decided to become an artist, I was not the best painter and so I was trying to find my way of not just being another mediocre painter.

I remembered the frustrations from when I was a kid that my grandmother would teach my sister how to embroider but she wouldn’t teach me because I was a boy. So when I decided to become an artist, I remembered that frustration and decided, “Well, now I’m a grown man and I can decide for myself to actually do embroidery.” I just taught myself how to embroider and that’s sort of what took me to the trajectory that eventually landed me on making the insulation.

Plexus No. 19 at Villa Olmo, Como, Italy

Plexus No. 19 at Villa Olmo, Como, Italy

How long was that time between you teaching yourself and then starting on the installations?

It took years. My background was in graphic design. I was really in this mentality of producing. I was used to having to produce and having deadlines. I think my biggest concern was that I was never going to be able to make a living because it took so long to make one single piece. But, you know, I stuck with it. I went to grad school and then in grad school, things evolved pretty fast. It’s when I started doing installations.

Plexus A1 at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Courtesy Conduit Gallery. Photo: Ron Blunt

Plexus A1 at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Courtesy Conduit Gallery. Photo: Ron Blunt

Do you do use any software to plan how the thread is going to be installed or is it drawn out?

I have come to an understanding of the geometric principles in play, so I don’t use any algorithms or software to help me figure out what’s going to happen or how a piece is going to be installed. I sketch on [Adobe] Illustrator; it’s really much faster to draw on the computer.

In very few instances, I do rely on 3D software just to make sure that we have high clearances. Especially when working on commissions where you don’t want people to be able to touch it because otherwise, it’s not going to last.

Plexus No. 24 at the Contemporary Art Museum, Houston, Texas

How has the conceptual basis for these vibrant installations changed over time? Has it shifted or have you learned new things by doing them?

[The installations started off as a big experiment with the material and what the material was. I started doing embroidery because I wanted to challenge the notions of masculinity that I grew up with and challenging the patriarchy in my own small way. I really liked, in the beginning, that how these massive installations were stemming from that idea. I still see that connection [today].

People are not necessarily going to see that when they look at the installations, but I still feel that it’s an extension of that embroidery practice [combined with] experimentation with the material and using the material of clothing in an architectural scale.

Plexus C18 at the San Antonio Airport

[continued] So that component started surfacing at the beginning—how buildings and clothing both have the function of sheltering. But then when you use the material of the clothing on an architectural scale, you lose that physical sheltering quality, but it gets transformed into this very childlike quality. It becomes like a sheltering of the soul in that way.

[The sheltering of the soul] started surfacing once I was working with thread for a while and then I realized that these pieces were really material. That’s when I decided to use the full spectrum [of color] to reinforce the idea of light because they kind of look like frozen rays of light in space.

And because I see how people really react to these pieces, it almost feels like when people encounter my work, they are having an immediate reaction. You can see their human masks fall and they just go to this childlike wonder space. [The installations] have become a sort of catalyst to have a sensory quality of bringing people to a place of inner joy.

Plexus No. 30 at the Newark Museum

So when you create these pieces is that “inner joy” and what the viewer might feel now at the forefront of your mind?

It is, and the other thing is more formalistic qualities and how they relate to the [specific] space they’re going to be in and how the insulation is going to activate a space. There’s this sort of unspoken dialogue between me and the building of, like, what is the building asking of me so I can translate it into an installation.

One of the things that I really enjoy is being in a new space and wondering how can I do something here that is going to make me push the work. I think that the work has been evolving very subtly over the years. I revisit things and make a subtle change or striking change. I really try to not just hash out the same thing over and over but really try to figure out how the work will unfold over time.

Plexus No. 31 at the Newark Museum

What are you working on now?

I just did an installation for the launch of a line of carpet that I collaborated on with Mannington Commercial. It’s called the Moiré collection and it’s inspired by the installations.

Plexus No. 34

Plexus No. 36 at the Denver Art Museum

Gabriel Dawe: Website | Instagram | Facebook

My Modern Met granted permission to use photos by Gabriel Dawe.

Related Articles:

Embroidery Artists Are Using a Needle and Thread to “Paint” Gorgeous Stitched Art

Indoor Rainbow Made of Thread Flows Through the Toledo Museum of Art

What is Installation Art? | History and Top Art Installations Since 2013