Artist’s recreation of Epiatheracerium itjilik, at its forested lake habitat, Devon Island, Early Miocene. The plants and animals shown are based on fossil finds at the site, including the transitional seal Puijila darwini. (Photo: © Julius Csotonyi)

Experts from the Canadian Museum of Nature (CMN) have made an important discovery about rhinos. In the Haughton Crater in the Canadian High Arctic, researchers have uncovered the northernmost species of “Arctic rhino” called Epiatheracerium itjilik. Epiatheracerium is the genus of rhinoceros, and itjilik means “frost” in Inuktitut. The published study, titled Mid-Cenozoic rhinocerotid dispersal via the North Atlantic, uses the rhino finding as evidence for the presence of the North Atlantic Land Bridge for 20 million years longer than previously understood.

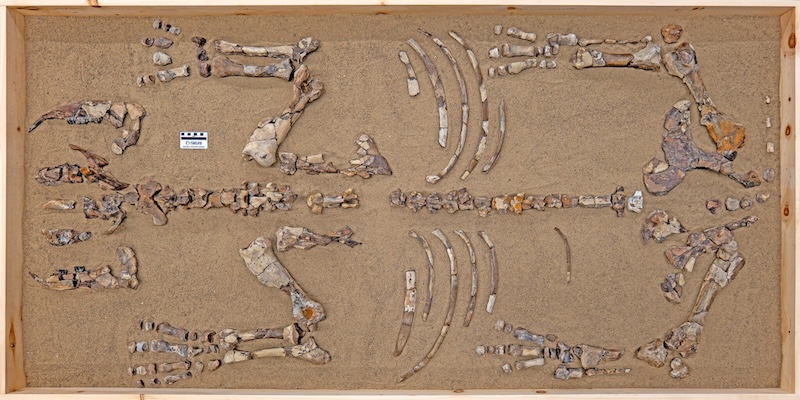

Most of the bones were excavated by Dr. Mary Dawson from the Haughton Crater on Devon Island, Nunavut, in 1986. More expeditions to the same site by CMN in the late 2000s, where Dawson was joined by Rybczynski and Gilbert, later uncovered additional fossils. The expeditions yielded three-quarters of the new species’ skeleton, which is an uncommonly large number in archeology. It’s also in excellent condition for being 23 million years old. The specimen shows that this species was on the small side, similar to modern Indian rhinos, but hornless.

Rhinos have roamed five of the seven continents, with the exceptions being South America and Antarctica, throughout their over 40 million-year history. “Today there are only five species of rhinos in Africa and Asia, but in the past they were found in Europe and North America, with more than 50 species known from the fossil record,” according to Dr. Danielle Fraser, the study’s lead author and head of palaeobiology at the CMN. E. itjilik dates back to approximately 23 million years ago, during the Early Miocene era.

This discovery is important for our understanding of the biogeography of rhinos. The creature migrated via the North Atlantic Land Bridge (NALB), which is a theory proposing that during the last Ice Age, there was a land mass connecting Europe, Greenland, and Canada. Previously, scientists thought this bridge became unusable 56 million years ago during the Eocene Epoch. However, after the discovery of E.itjilik and and the publication of the study in the Nature Ecology & Evolution journal, evidence suggests that it was used for a significantly longer period–specifically, 20 million years, or two epochs longer. The location of the discovery in the Canadian High Arctic, an archipelago between the continental Canadian mainland and Greenland, is evidence that the rhinos were still using the NALB in the Oligo-Miocene era.

This shifts our understanding of all Arctic discoveries and underscores how science is constantly learning and evolving. Fraser says, “It’s always exciting and informative to describe a new species. But there is more that comes from the identification of Epiaceratherium itjilik, as our reconstructions of rhino evolution show that the North Atlantic played a much more important role in their evolution than previously thought. More broadly, this study reinforces that the Arctic continues to offer up new knowledge and discoveries that expand on our understanding of mammal diversification over time.”

A new rhino species called Epiatheracerium itjilik was discovered as being 23 million years old.

Overheard view of the fossil of Epiatheracerium itjilik. About 75% of the animal’s bones were recovered, including diagnostic bones such as the teeth, mandibles and parts of the cranium. (Photo: Pierre Poirier © Canadian Museum of Nature)

About 75% of the fossilized bones were recovered from the dig site in the Canadian High Arctic—a rare and exceptionally large number.

Marisa Gilbert (left) and Dr. Danielle Fraser with the fossil of Epiaceratherium itjilik in the collections of the Canadian Museum of Nature. (Photo: Pierre Poirier. © Canadian Museum of Nature.)

The dig site was in the Haughton Crater, a fossil-rich zone in the archipelago between Greenland and the Canadian mainland.

The Haughton Crater on Devon Island is a rich source of Early Miocene fossils, including the bones of Epiaceratherium itjilik. (Photo: Martin Lipman © Canadian Museum of Nature)

The area was part of the North Atlantic Land Bridge (NALB), and the discovery of E. itjilik suggests that the NALB was used about 20 million more years than previously thought.

Dr. Natalia Rybczynski (foreground, left) and Dr. Mary Dawson sift for fossils at Haughton Crater, 2007. (Photo: Martin Lipman © Canadian Museum of Nature)

This important archeological discovery not only uncovered a new species, but it also revealed new evidence that will reshape the way we think about the history of the Arctic.

Dr. Natalia Rybcynski (right) and Jarloo Kiguktak examine bones collected during an expedition to the Haughton Crater, 2008. (Photo: Martin Lipman © Canadian Museum of Nature)

Sources: Evidence of Rhino Living in Frigid Arctic Circle 23 Million Years Ago Discovered in New Fossil, Museum scientists describe an extinct rhino species from Canada’s High Arctic, Mid-Cenozoic rhinocerotid dispersal via the North Atlantic

Related Articles:

Archeologists Discover Neolithic Earthworks That Are 2,000 Years Older Than Stonehenge

Trove of Incredibly Well-Preserved Fossils Found in Australian Red Rocks

Researchers Discover 300,000-Year-Old Human Footprints Offering Insight Into Early Human History