A leaf from a Gradual, showing the initial “P” with the Nativity. Created by Attavante degli Attavanti in ink, tempera, and gold on vellum, 1495. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Imagine spending hours pouring over a dusty old book, painstakingly copying the text word for word onto a new page in a blank volume. This laborious process was necessary in the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance. Before the introduction of moveable type in Europe during the 15th century, books were written out in ink by hand. These books are called manuscripts, derived from the Latin manuscriptus. Manu means “by hand” and scriptus means “written.”

Manuscripts are found all over the world, with some texts dating to antiquity. However, the tradition of illuminated manuscripts—intricate, decorated handwritten texts—developed in late antiquity at the dawn of the Dark Ages. Despite the misnomer, the production of illuminated manuscripts was an important industry in the Early Medieval Period. The production of books became a lucrative, rich art form. Illuminated manuscripts were luxury goods—expensive and labor-intensive. The earliest texts were typically religious in nature, including Gospels and Lectionaries.

The illuminated manuscript tradition is therefore highly associated with medieval Christian Europe. However, the Islamic courts of medieval Iberia and the later Ottoman Empire had rich traditions of manuscript production and illumination. Extravagantly decorated texts are also found in the traditions of China, Japan, and India—among other artistic traditions.

Although this article primarily focuses on the illuminated manuscripts of Europe, explore the brilliant volumes of these other traditions through exhibits on Jain manuscripts from India or Nepalese Buddhist texts.

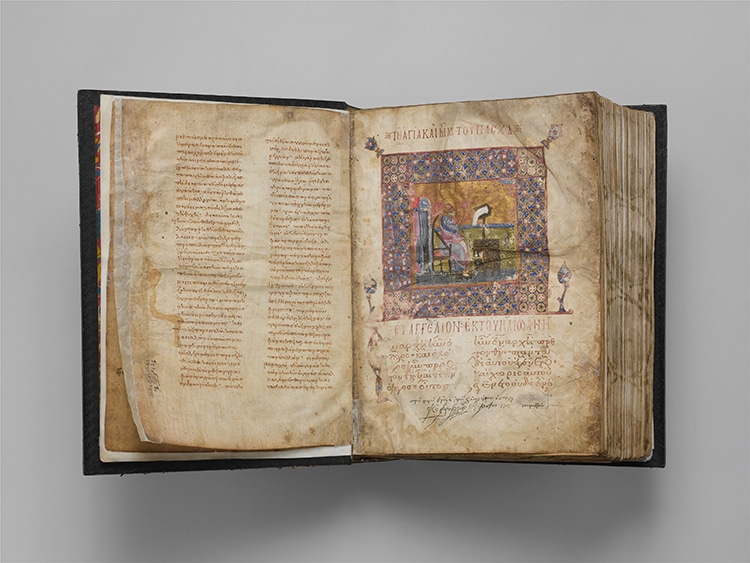

The Jaharis Byzantine Lectionary,

circa 1100 in Constantinople. Tempera, gold, and ink on parchment with leather binding. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

What is a medieval manuscript?

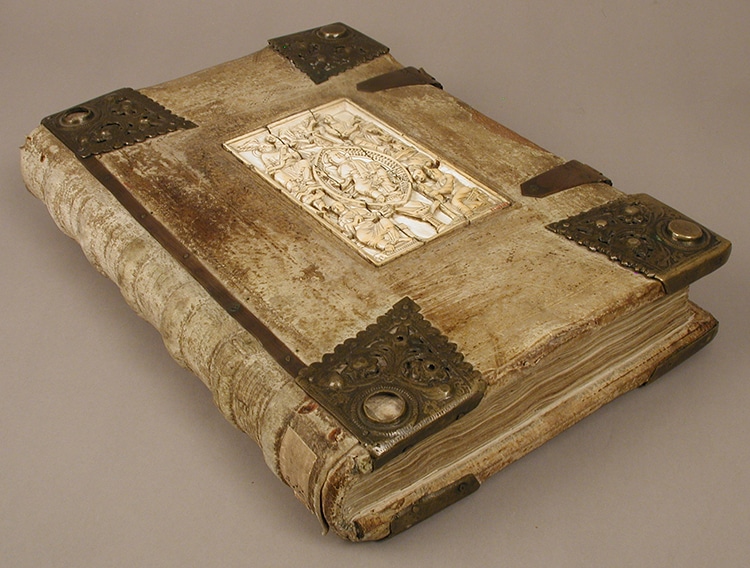

An Ottonian manuscript bound in leather with ivory accents, made in Germany circa 1000 to 1100. The front plaque depicts Christ in Majesty and the Four Evangelists. The original manuscript was eventually removed and the cover used for a 15th century Gospel lectionary. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Manuscripts are texts or books written by hand. These were the only books available in medieval Europe, before the advent of the printing press in the 15th century. Typically, a manuscript was a codex—a bound volume composed of sheets of parchment (animal skin). The best quality codexes used fine calfskin called vellum. The pages were sewn together along one edge and encased in ornate covers with leather, gold, ivory, and even precious jewels.

The text of a manuscript was handwritten in ink. Illustrations and illuminations (decorations) were painted in tempera (color pigment bound by an egg base). Gold leaf often added a gilded final touch. While not all manuscripts are so ornately illuminated, common textual features of these medieval books include dramatic drop caps, marginalia, and ornate scripts. Most early illuminated manuscripts were religious texts, but the tradition blossomed to include epic poems, histories, and allegorical stories.

Who created illuminated manuscripts and how?

Illustration of a scribe from the Roman de la Rose manuscript, an allegorical poem written in Old Frenchin the 14th century. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The earliest evidence of illuminated manuscripts in Europe and the Byzantine Empire date from the 7th century CE. Manuscript production quickly became an important craft. As Christianity was a central part of medieval Western European and Byzantine life, devotional books were commissioned by religious organizations, churches, and nobility. In Islamic Spain, classical works from Greek and Roman traditions were produced in addition to religious works; thanks to the work of these early Islamic scholars, critical knowledge was preserved and expounded upon.

Christian monasteries were the center of this manuscript production in early medieval Europe. Literacy was limited at the time but monks were more often literate, artistic, and theologically versed. As a result, monasteries became centers for the production of illuminated religious texts for their own use as well as sale to external clientele. Later in the medieval period, manuscripts were sometimes created by lay craftsmen who worked as scribes or illuminators in the sciptoria (writing rooms) of monasteries or in secular workshops. A manuscript would often pass through several hands, from the binder to the scribe to the illuminator.

What literary themes did these works address?

A book of flower studies by the Master of Claude de France, circa 1510–1515. This book dates from the tail end of the European illuminated manuscript tradition, as the printing press soon revolutionized the book industry. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Many medieval manuscripts were religious in nature. Books of Hours were particularly ornate. These books designated a prayer cycle for the lay owner, set out by the days and hours. Each prayer was accompanied by rich illustrations depicting devotional scenes as well as the mundane activities of the day. The purchaser could customize the prayers and images of their book upon commission. Some chose to have themselves illustrated among figures such as the Virgin Mary and Christ Child.

Manuscript Bibles were also painstakingly created in medieval monasteries and workshops. Large volumes were used in mass as priests read aloud. Collections of the Psalms were likewise created for communal use. Smaller volumes of both devotional texts could be carried around by itinerant preachers or wealthy, devout nobles. Few illuminated Qur’an have survived from Islamic Iberia, but many beautiful examples of geometric flourishes and gold details endure in volumes from Egypt and other realms. Combined with the exquisite calligraphy of the Qur’an, the illumination helps guide worship by indicating divisions in the text and at what point a worshipper should prostrate themselves.

Medieval Jewish sacred texts were also richly decorated. As in Islam, scripture prohibited illustrating humans and animals. However, medieval Hebrew Bibles were richly ornamented out of respect for the text and sacred study. Some early texts from the Near East and Spain absorbed the geometric, abstract styles of contemporary Islamic manuscripts. From the 13th to 15th centuries, French, German, and Italian manuscripts included Gothic styles similar to contemporary Christian Bibles. From Passover liturgies to marriage contracts, illuminated Hebrew manuscripts form a beautiful sacred literature tradition.

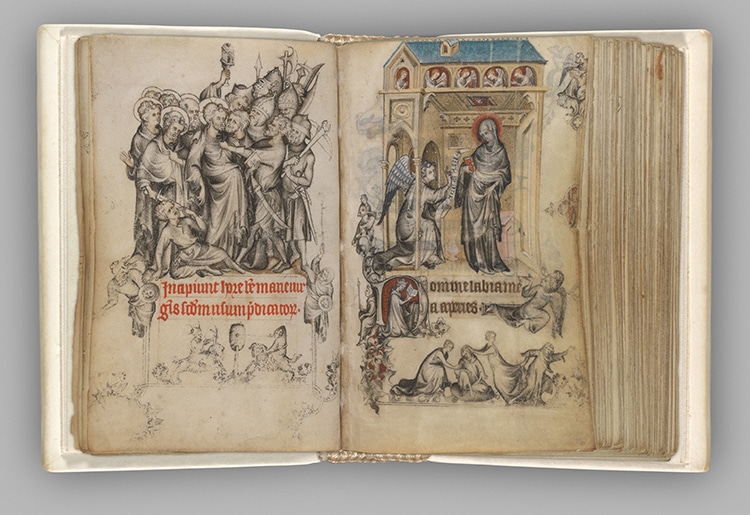

The Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, Queen of France, a book of hours crafted circa 1324–28 by Jean Pucelle. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Despite the religiosity of the medieval period, secular texts were also produced. Bestiaries and herbals lent themselves naturally to illustration. Other texts focused on the stars, describing constellations and the astrological predictions which could be derived from the night sky. Saints’ lives and the travels of famous adventurers were also subjects in the later period of medieval manuscript creation. Other handwritten documents—such as the king’s orders and maps—were also illuminated.

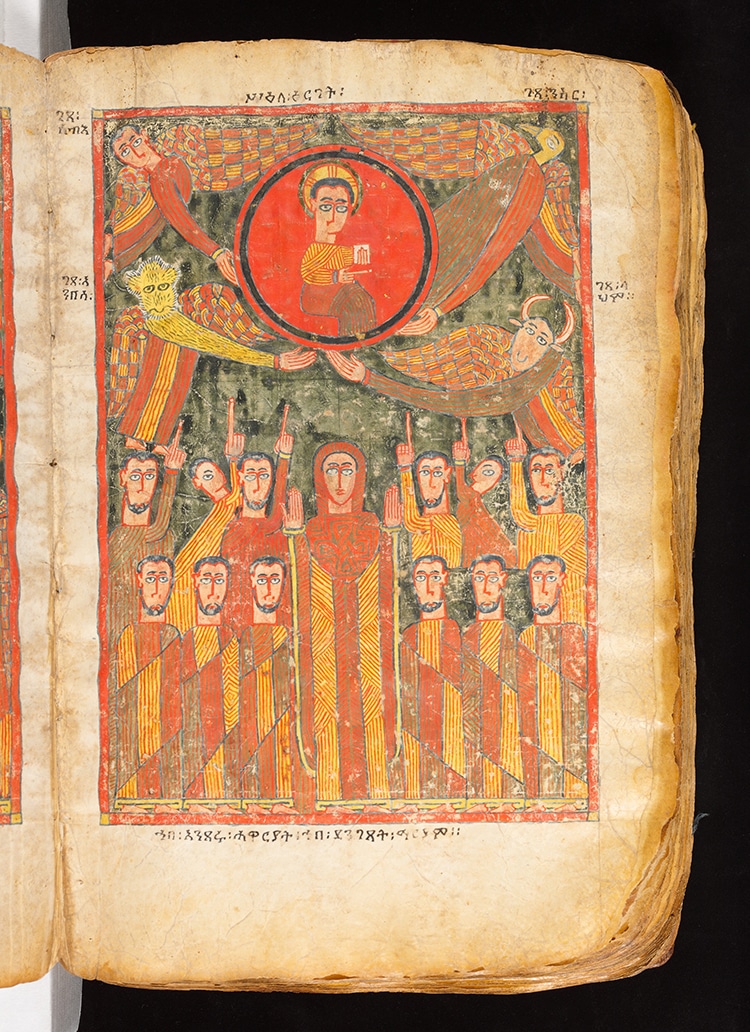

An Illuminated Gospel from the late 14th–early 15th century in the Amhara region of Ethiopia. Made of vellum, acacia wood, tempera, and ink, this manuscript was crafted at a monastery. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Explore some famous examples of these exquisite volumes.

The Book of Kells

The Book of Kells, a 9th century Latin Gospel created in a monastery in England, Scotland, or Ireland in the 9th century. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Perhaps most famous among illuminated manuscripts is the Book of Kells. Held in the Library at Trinity College Dublin, the four-gospel volume was created around 800 in a monastery scriptorium. This makes it not only the most famous manuscript but also an exceptionally early example of lavish embellishment. The intricate designs of the stunning illuminations are thought to have been created by three artists working in concert. Ironically, the text itself was poorly copied and is missing words.

Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry

Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, a 15th century book of hours created by the Limbourg brothers for John, Duke of Berry. This page shows the month of October. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry is a famous Book of Hours commissioned by John, Duke of Berry. The French duke was the son of King John II of France. His prayerbook reflects his fortune and status as a royal. It is in the International Gothic style and created by the famous Dutch artists, the Limbourg brothers, as well as several later unknown painters. Miniature scenes, marginalia flourishes, and ornate initial letters bedeck the 206 parchment pages and architectural details frame the tableau.

The book depicts scenes from the life of Christ, as well as the Duke and his wife in devout prayer. The Duke’s everyday life also appears; one scene, for example, shows a New Year’s celebration among courtiers. To see another stunning example of a Book of Hours, explore the Black Hours currently held at The Morgan Library & Museum.

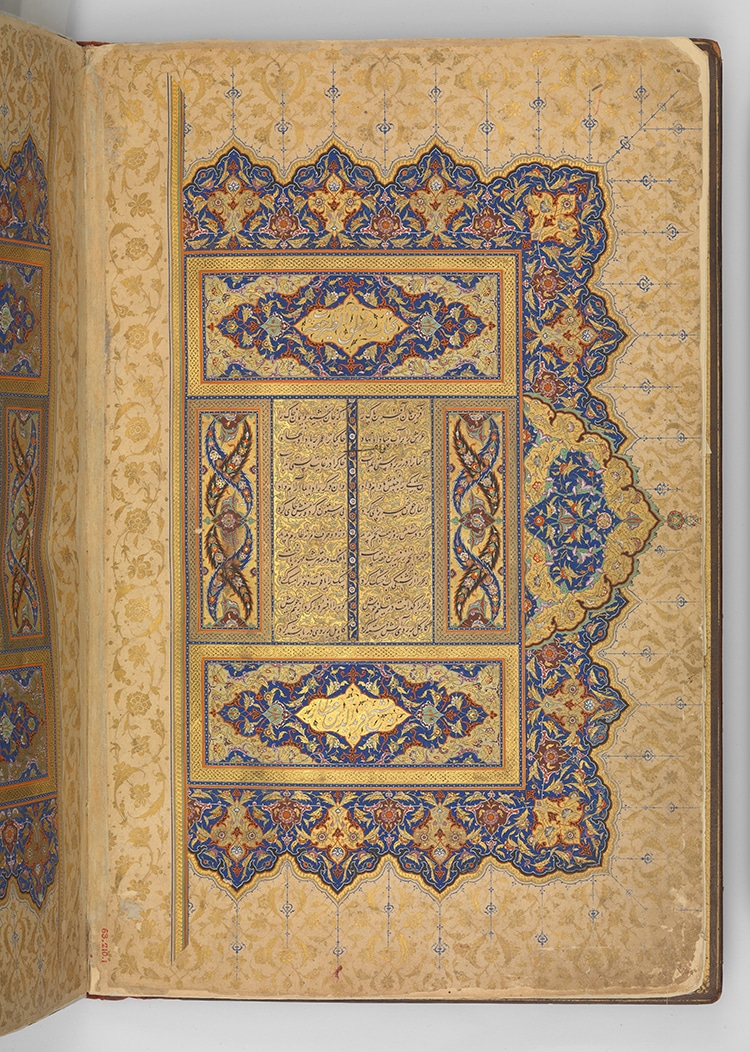

A frontispiece of a manuscript of the Mantiq al-tair (Language of the Birds), a mystical poem by Farid al-Din ‘Attar. The text was written in A.H. 892 (1487 CE), but the illumination was added by Zain al-‘Abidin al-Tabrizi around 1600. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

The Mantiq al-tair (Language of the Birds) is a Persian mystical poem by Farid al-Din ‘Attar. The Sufi poet penned the verse during the 12th century. It was later immortalized in multiple illuminated volumes. Like in Europe, Persian nobles appreciated elegant volumes to add to their libraries. Illumination was combined with marbled paper and elegant calligraphy for this volume, illustrated around 1600. Fit for a king, the volume was in the collection of the Safavid ruler Shah ‘Abbas I.

From sacred texts to poetic tales, medieval illuminated manuscripts were expensive and artistic. They are even more precious today for the window they provide into the history, religious culture, and artistic innovations of a bygone age.

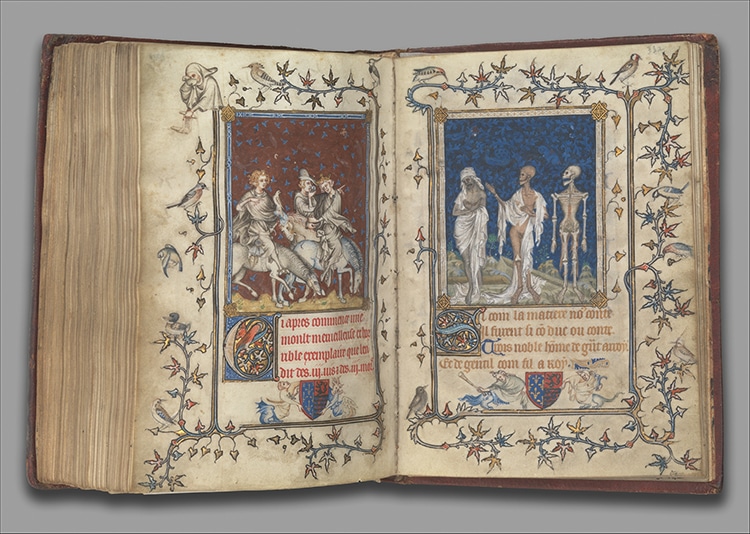

The Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, Duchess of Normandy, created before 1349 and attributed to Jean Le Noir. (Photo: The Metropolitan museum of Art, Public domain)

Related Articles:

800 Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts from France and Britain Available Online

Europe’s Oldest Intact Book Is Discovered Inside the Coffin of a Saint

These Four Manuscripts Contain Almost All Surviving Old English Poetry

Medieval Illuminated Manuscript Exploring the Majesty of Animals Digitized and Placed Online