Photo: Kelly Richman-Abdou / My Modern Met

When you think of the French Revolution, what comes to mind? Most likely, you picture chaos on the streets of Paris; maybe you imagine the movement’s most triumphant figures; or, perhaps you simply see the fluttering French flag. In Liberty Leading the People, a large-scale piece painted in 1830, Romantic artist Eugène Delacroix explores all three of these motifs, culminating in a canvas that epitomizes the spirit of the Revolution.

Who was Eugène Delacroix?

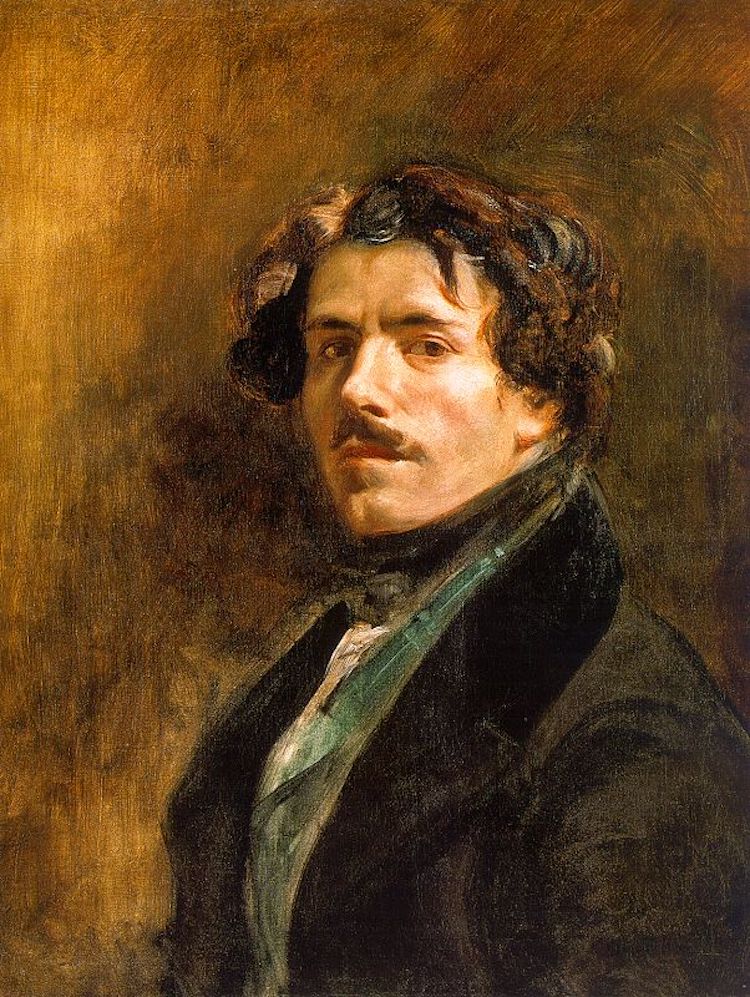

Eugène Delacroix, “Self-Portrait with Green Vest,” 1837 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) was a leader of the Romanticism art movement and an influential figure in the work of the Impressionists. His oeuvre spanned contemporary events, mythological scenes, Orientalism, and portraiture.

Delacroix utilized the emotional qualities of color and expressive brushstrokes to create a range of spectacular pieces inspired by the political events of Europe, mythology, and his visits to North Africa. The evocative qualities of his paintings, which were unprecedented for the time, had a lasting impact on future artists.

What was the French Revolution?

The French Revolution was a period of political and social turmoil that consumed the country in the late 18th century. The movement officially began with the Storming of the Bastille, an event that took place on July 14, 1789.

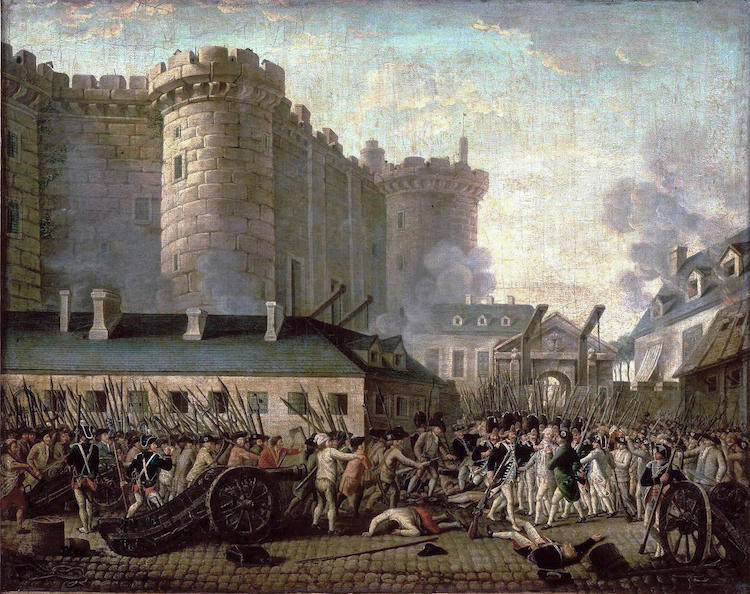

” Storming of the Bastille and arrest of the Governor M. de Launay, July 14, 1789″ (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

On this day, a group of rioters—comprising mostly craftsmen and shop owners—violently invaded the Bastille, a medieval fortress-turned-state prison. In addition to freeing political prisoners, the revolutionaries hoped to gain access to the gun powder that was stored on the premises.

What were these rioters rebelling against? Ultimately, they were unhappy with France’s royal family, whose excessive wealth highlighted—and contributed to—their own suffering. Overly-taxed and underpaid, the people of France were unable to feed themselves and their families, leading to a series of battles. While most of these clashes occurred a period of ten years (1789 through 1799, which today is known as the French Revolution), some continued through the 19th century, including the July Revolution, an event Delacroix documents in Liberty Leading the People.

The July Revolution

Léon Cogniet, “Scene of July 1830,” 1830 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Delacroix painted Liberty Leading the People in 1830, the same year that the July Revolution radically altered the course of French history. The July Revolution—also known as the Second French Revolution and Trois Glorieuses (“Three Glorious Days”)—was a conflict that took place on the 27th, 28th, and 29th of July.

Like those fought during the French Revolution, this battle occurred as the result of differing views on who should rule France. In this case, the two sides supported either the House of Bourbon or the House of Orléans. At this point, Charles X of the House Bourbon had been in power since 1824. However, following the three-day battle, he was overthrown and succeeded by Louis-Philippe, a leader of the House of Orléans.

This major overhaul shifted power from the Bourbon Restoration to the July Monarchy, a kingship based on a constitution, marking a major milestone in France’s string of revolutions—and inspiring Delacroix to paint Liberty Leading the People.

Liberty Leading the People

Eugène Delacroix, “Liberty Leading the People,” 1830 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Composition

Painted in the fall of 1830, Liberty Leading the People offers contemporary insight into this major event. Set on the streets of Paris (Notre-Dame Cathedral can be seen in the smoke-filled background) and full of symbolism, the large-scale painting shows Parisians following a female figure. Intended to embody the concept of liberty, this allegorical character is commonly believed to be an early version of Marianne, a personification of the French Republic.

All of the figures are arranged in a pyramid shape with Marianne at the top, emphasizing her importance in the composition and guiding the viewer’s eyes across the canvas of the painting.

Symbolism

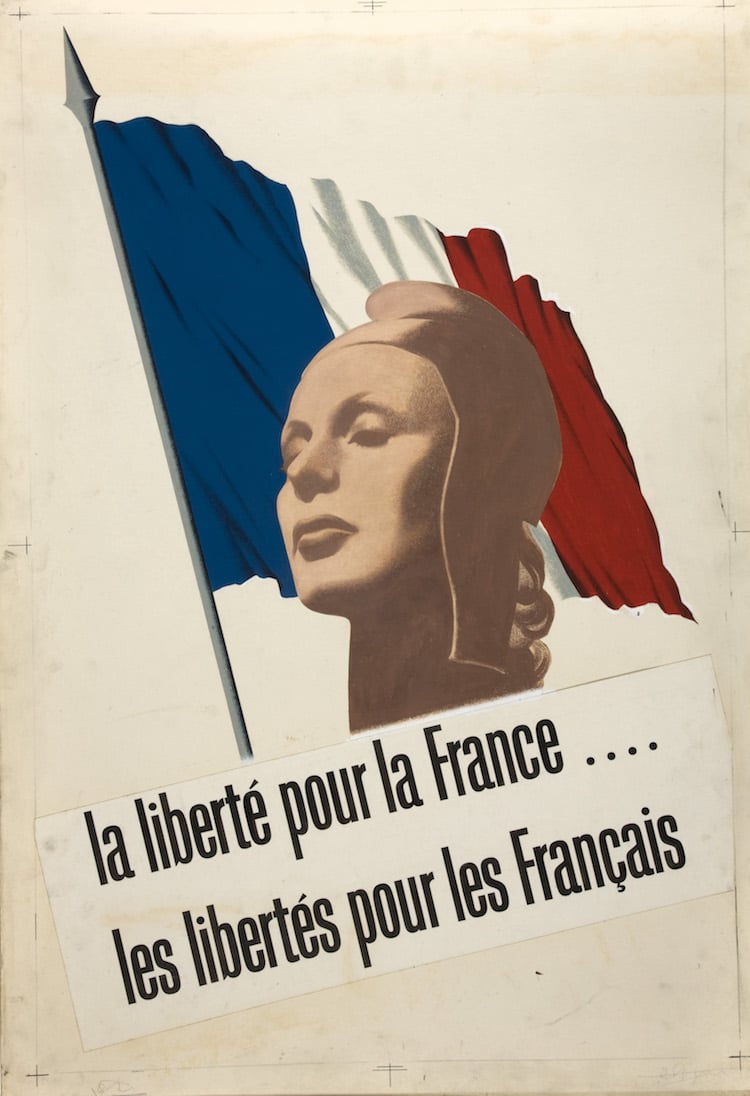

Since the French Revolution, Marianne has served as a national symbol of France. She is often shown triumphantly clasping the tricolour—the red, white, and blue flag of the revolutionaries and, today, of the country—and sporting a Phrygian cap. This hat was strategically chosen by Revolutionaries for its symbolism, which was rooted in ancient times.

“The Phrygian cap, the symbol of liberty, used to be worn by freed slaves in Greece and Rome,” France’s Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs explains. “Mediterranean seamen and convicts manning the galleys also wore a similar type of cap, and revolutionaries from the South of France are believed to have adopted the headgear.”

“Freedom for France…. freedom for the French” poster, 1940 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Important Figures

With a flag in-hand and a Phrygian cap on her head, Lady Liberty is undoubtedly the painting’s symbolic star. However, she is not the only figure worth examining. Behind her, a crowd celebrates their victory. In order to capture the widespread diversity of the revolutionaries, Delacroix decided to depict people from all walks of life, including a wealthy individual in a top hat, students, soldiers, and even a young working-class boy pointing a pistol in the air.

Intent

Delacroix painted Liberty Leading the People in order to voice his support for the cause, commemorate those who risked their lives during the July Revolution, and, above all else, honor France. “I have undertaken a modern subject, a barricade, and although I may not have fought for my country, at least I shall have painted for her,” he revealed. “It has restored my good spirits.”

Provenance and Legacy

In 1831, the French government purchased the painting. While it was intended to adorn the throne room of Paris’ Palais du Luxembourg, it was eventually deemed “too revolutionary” and given back to Delacroix. Over the next few decades, it was exhibited in different locations, until it finally found a permanent home in the Louvre Museum in 1874.

Since then, Liberty Leading the People has been a highlight of the museum’s French painting collection. Today, it hangs among other large-scale Romantic works. Though equally dramatic, Liberty Leading the People stands out from these canvases, as it offers viewers a perfect “blend of document and symbol, actuality and fiction, reality and allegory.”

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

‘The Death of Marat’: A Powerful Painting of One of the French Revolution’s Most Famous Murders

How David’s ‘Death of Socrates’ Perfectly Captures the Spirit of Neoclassical Painting

5 Rock-Solid Facts About Paris’ Amazing Arc de Triomphe

130-Year-Old Video Footage Lets You Explore Everyday Life in 1890s Paris