Giorgio de Chirico, “The Soothsayer’s Recompense,” 1913. (Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art)

A little over a century ago, in 1924, André Breton published his Manifesto of Surrealism. Across some 20 pages, the French writer lamented that, as people grow older, they inevitably abandon their imaginations in favor of pragmatism. He did, however, present a solution to this conundrum: leaning into, rather than eschewing, a childlike sense of creativity. It turns out he was right, and thus the surrealist movement was born. Now, 100 years after its birth, a landmark exhibition dedicated solely to surrealism has finally arrived in the United States, following successful runs at the Centre Pompidou, the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, the Fundación MAPFRE, and the Hamburger Kunsthalle.

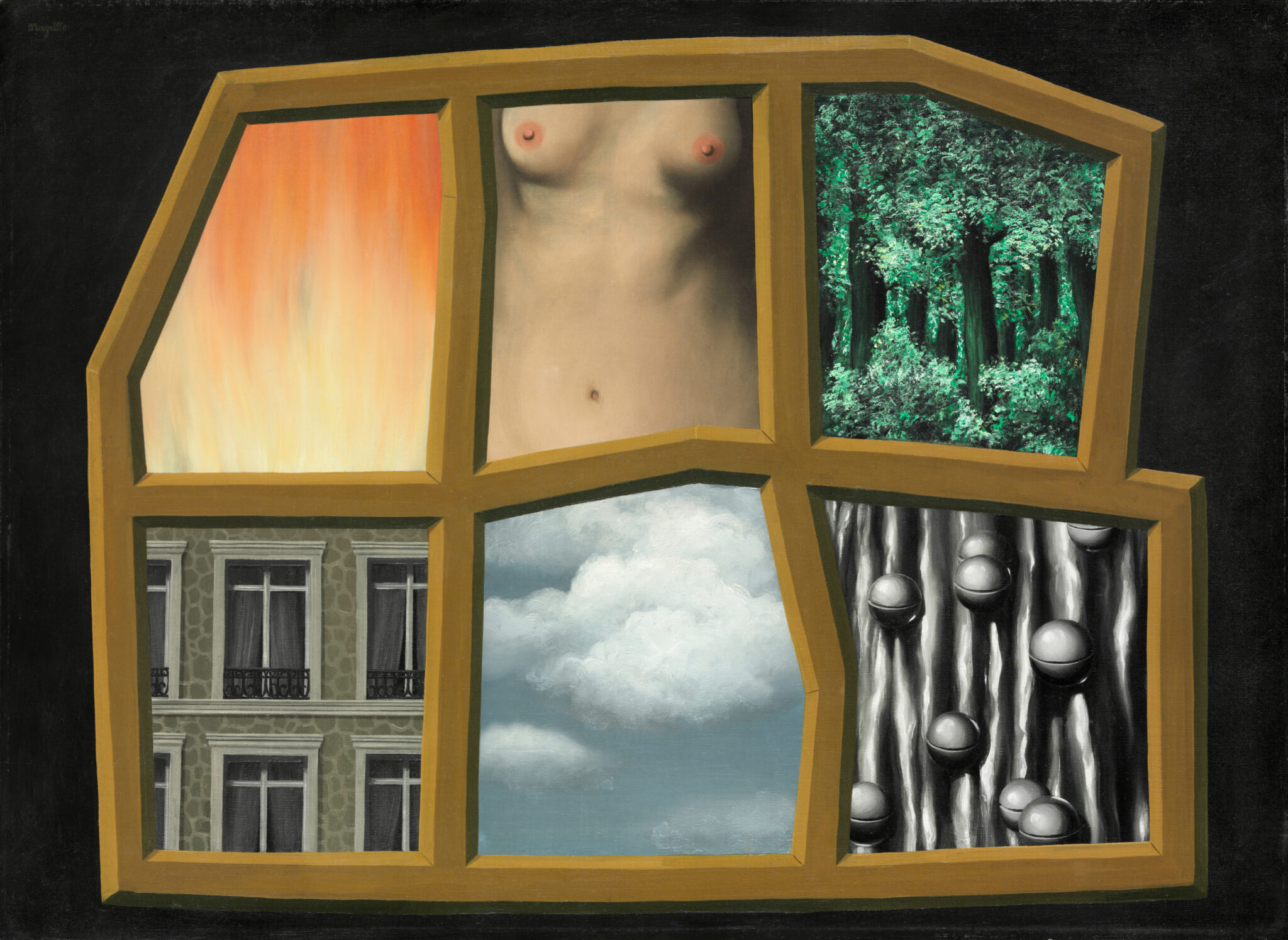

Currently on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA), the exhibition’s sole U.S. venue, Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100 gathers about 200 works by more than 70 surrealist artists. Pieces range from fuzzy umbrellas suspended in midair to paintings of unsettling, chimeric creatures, providing a kaleidoscopic glimpse into one of the world’s most influential artistic movements. As is to be expected, the exhibition highlights surrealism’s leading talents, including Salvador Dalí, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, René Magritte, Joan Miró, and Man Ray, among others.

Despite its ambitious scope, Dreamworld does acknowledge surrealism’s limitations. A vast majority of the exhibition’s works were produced by men, but there are still a few gems that challenge the assumption that women were entirely absent within 20th century modernism. Danish artist Rita Kernn-Larsen makes an appearance, for instance, with The Women’s Uprising, a moody painting from 1940 depicting a group of tangled trees, all bearing feminine features like breasts. Léonor Fini’s 1941 L’Alcove (Self-portrait with Nico Papatakis) offers a sensual, dreamlike scene in which the artist gazes longingly at a nude Papatakis—rather than the other way around. Jacqueline Lamba, Breton’s wife, contributes Behind the Sun, a layered, earthy canvas reminiscent of Picasso’s Cubist collages.

Perhaps most compelling of all, though, are works by artists like Claude Cahun and Toyen (born Marie Čermínová), both of whom resisted the gender binary entirely. Though a multidisciplinary artist, Cahun might have been most intriguing as a self-portraitist, assuming performative, surreal personae that resisted the period’s strict notions of femininity. Similarly, Toyen consistently refused feminine language markers and roles, all while producing erotic yet abstract paintings inspired by gender, sexuality, and desire. When juxtaposed with the male artists of the time period, such creatives as Cahun and Toyen complicate traditional understandings of surrealism as an exclusively male endeavor.

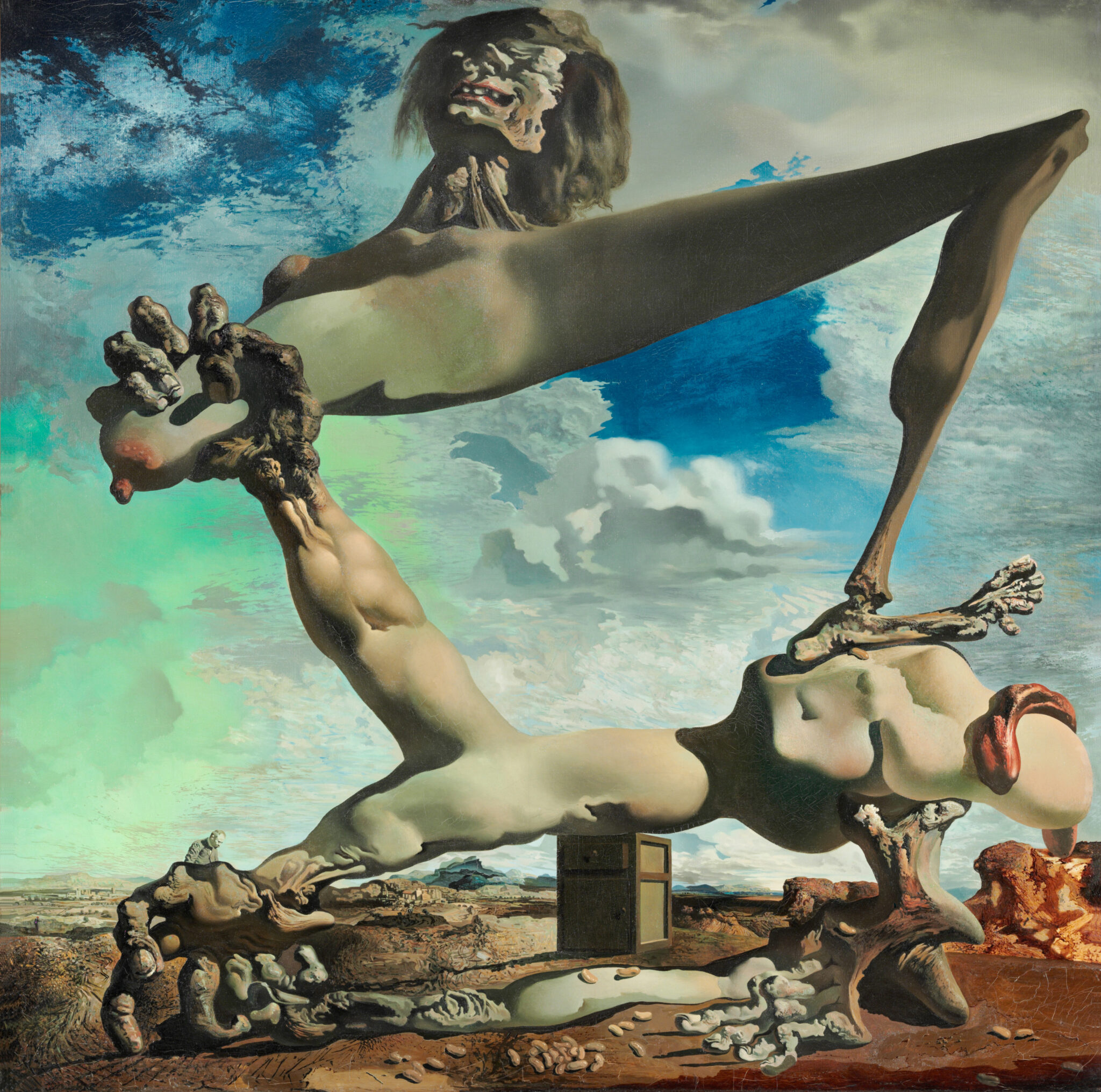

But Dreamworld is far from simply an overview. To help guide viewers through surrealist sprawl, the exhibition is organized into several thematic sections. In “Premonition of War,” for example, artists like Dalí, Ernst, and Pablo Picasso reimagine the devastations of war and totalitarianism as monstrous, terrifying creatures. “Exiles,” on the other hand, considers how surrealists working in France escaped to North America during the outbreak of World War II, settling in Caribbean ports, Mexico, and the United States. Exclusive to PMA, this section notably features Frida Kahlo’s 1936 My Grandparents, My Parents, and I, alongside paintings by Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko.

“This idea of finding a technique which evades your conscious control is really the central part here,” PMA curator Matthew Affron told WHYY in a recent interview. “What surrealism wanted, fundamentally, was a revolution in consciousness.”

And what a revolution this exhibition is. Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100 is currently on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through February 16, 2026.

After successful runs in Europe, Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100 has arrived at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the exhibition’s only U.S. venue, in celebration of the movement’s centenary.

Salvador Dalí, “Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War),” 1936. (Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art)

André Masson, “The Landscape of Wonders,” 1935. (Courtesy of the Guggenheim Museum)

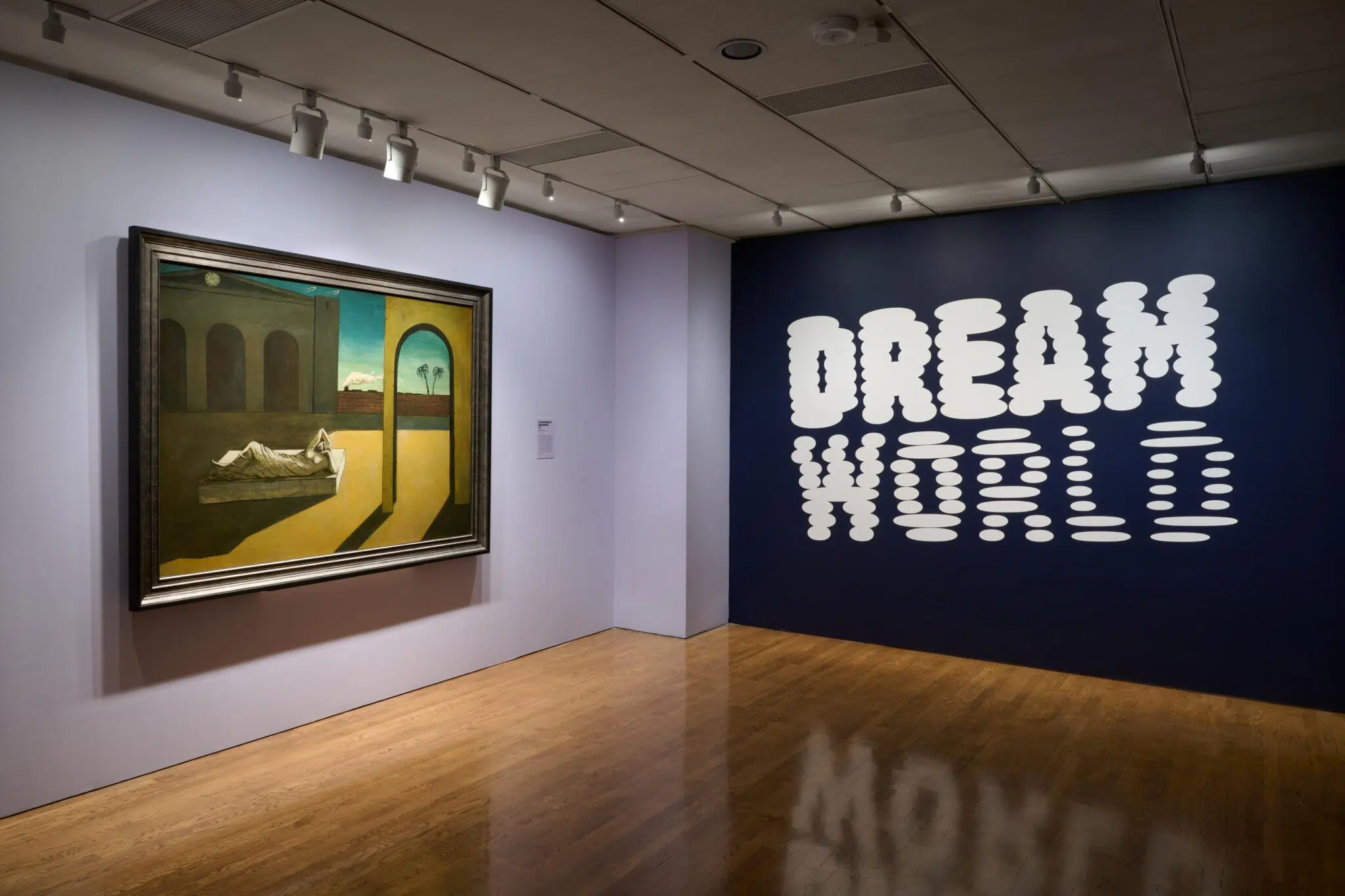

Installation view of “Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100,” now open at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Photo: Aimee Almstead)

Victor Brauner, “The Lovers (Messengers of the Number),” 1947. (Courtesy of the Centre Pompidou, Paris)

The exhibition gathers some 200 artworks by more than 70 surrealist artists, offering a generous glimpse into one of the world’s most influential artistic movements.

Installation view of “Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100,” now open at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Photo: Aimee Almstead)

René Magritte, “The Six Elements,” 1929. (Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Leonora Carrington, “The Pleasures of Dagobert,” 1945. (Courtesy of the Collection of Eduardo F. Costantini)

Installation view of “Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100,” now open at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Photo: Aimee Almstead)

Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100 is on view at PMA through February 16, 2026.

Salvador Dalí, ”Aphrodisiac Telephone,” 1938. (Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art)

Remedios Varo, “Icon,” 1945. (Courtesy of the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires)

Installation view of “Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100,” now open at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Photo: Aimee Almstead)

Installation view of “Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100,” now open at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Photo: Aimee Almstead)