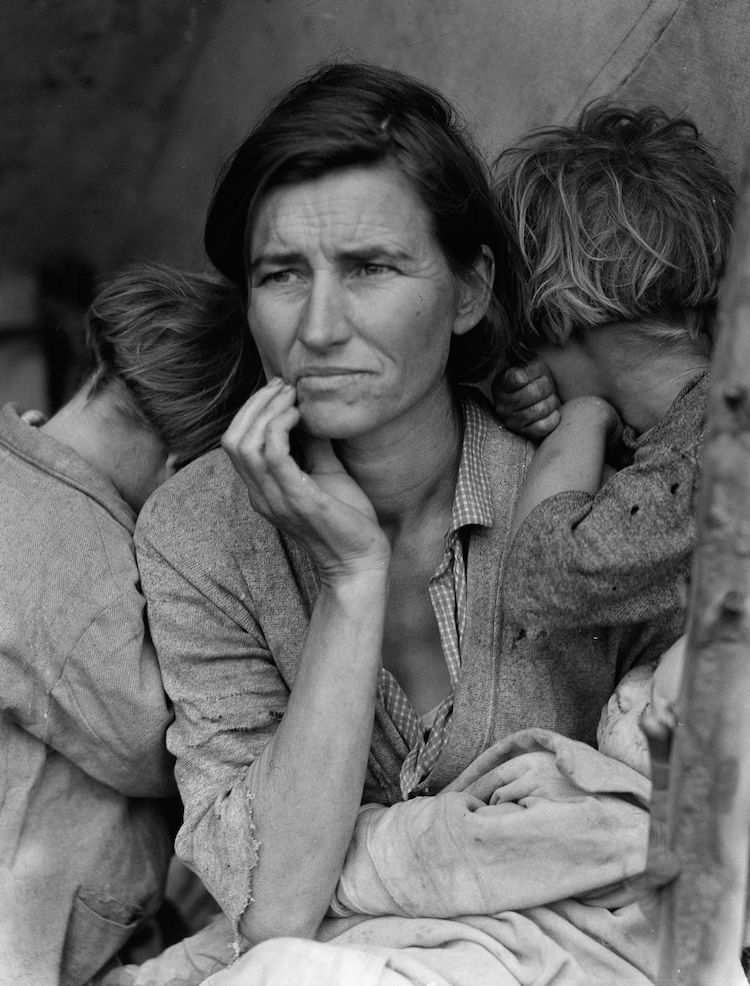

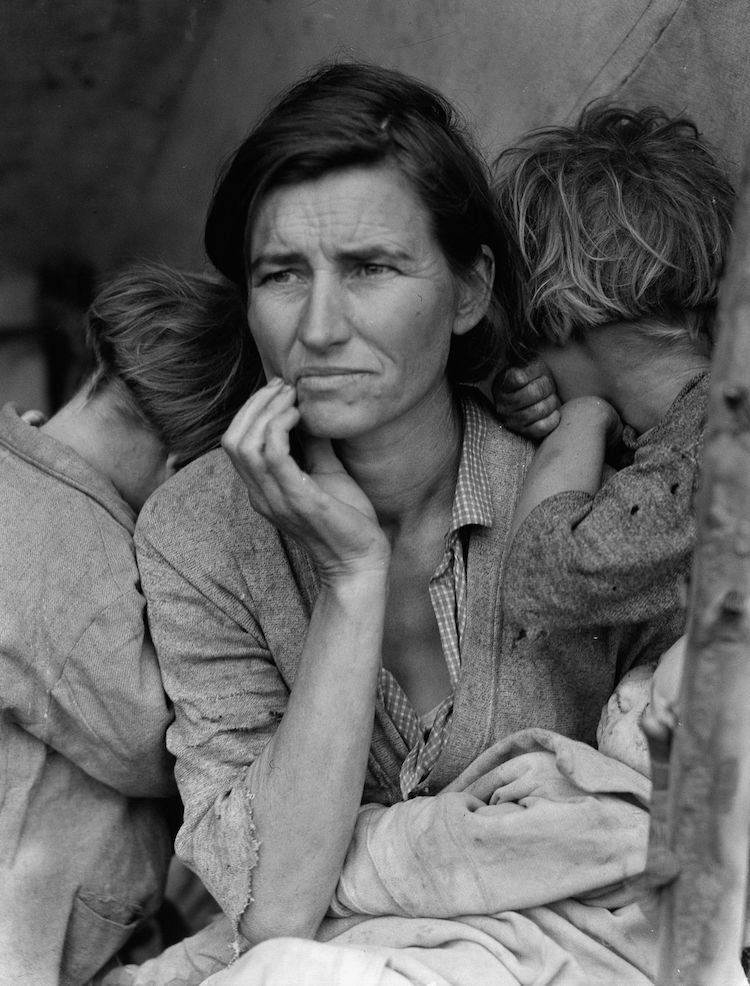

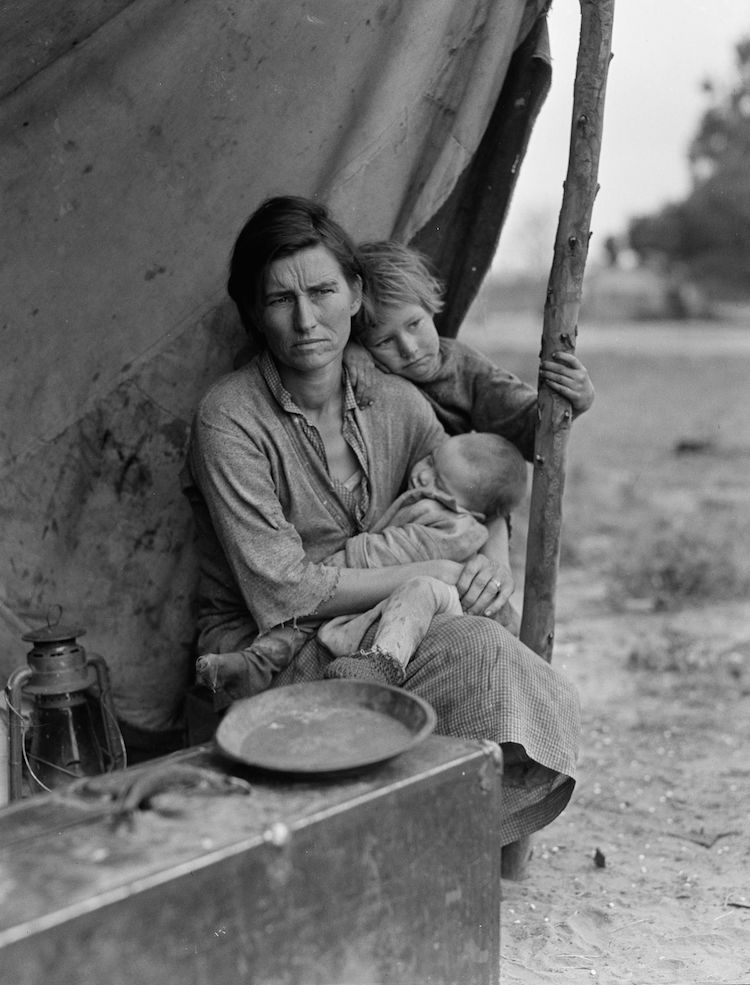

Dorothea Lange, ‘Destitute peapickers in California; a 32 year old mother of seven children.’

Photo: The Library of Congress

Throughout the 20th century, photojournalism shifted and shaped the way the public perceived the world around them. From 1930 through 1970, the field experienced a “golden age” due to technological advancements and an increasing interest in world affairs. One figure who helped to usher in this era was Dorothea Lange, an American photographer known for her images documenting the plights and perils of the Great Depression. While many of Lange’s intimate portraits of this period resonated with the public, none have had an effect as profound and wide-reaching as Migrant Mother, a photograph taken at the height of the Depression.

Context

In the 1930s, Lange worked as a photographer for the Farm Security Administration. Commissioned to document the impact of federal programs intended to improve rural communities, she was sent to locations across the country. In addition to this work assignment, however, Lange also found herself working on a personal project: photographing the real-life effects of the Great Depression.

Dorothea Lange in 1936

During one self-prompted visit to a campsite brimming with out-of-work pea pickers, Lange spotted a particularly downtrodden woman and immediately felt compelled to photograph her. “I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet,” Lange recalls in 1960 interview with Popular Photography. “I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her but I do remember she asked me no questions.” With the woman’s permission, she snapped 6 photographs, one of which being the now-iconic Migrant Mother.

Subject Matter

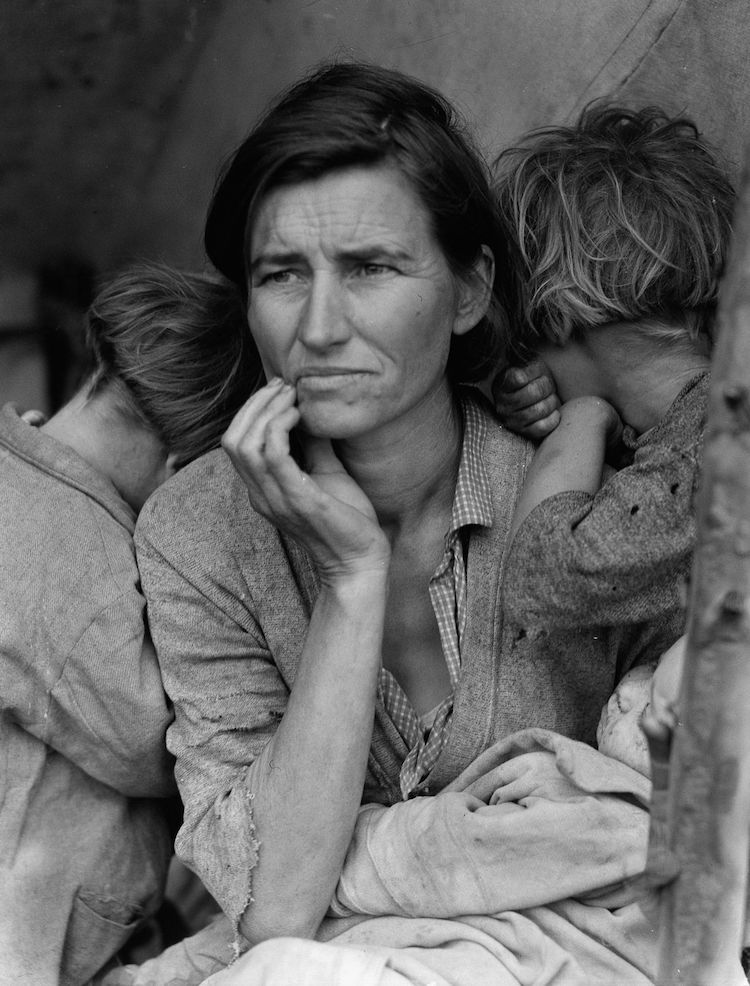

Migrant Mother depicts the female farm worker with 2 young children at her side and a sleeping baby on her lap. As she sits with her children, she stares into the distance and gently holds her hand to her face, suggesting that she is deep in thought. With her worried expression, worn-out clothes, and seemingly unwashed children, it is clear that this family—like countless others during the 1930s—is struggling.

Story

So, who is this subject?

When she took the intimate series of photographs, even Lange was unsure. All that she knew was her age, the fact that she was a mother, and that she was undoubtedly suffering. “I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was 32. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food.”

It was over 40 years later until the woman’s identity was revealed. Her name was Florence Thompson, and she was a widowed mother of 7 from Oklahoma. In the 1920s, she and her husband, Cleo, migrated to California, where Cleo would tragically die of tuberculosis in 1931. Pregnant with her sixth child, she was forced to take on a number of jobs to support her family. “I worked in hospitals. I tended bar. I cooked. I worked in the fields. I done a little bit of everything to make a living for my kids,” she recollected in 1979. That need to support her family landed them in the camp, where she and other struggling farmers coped with the fact that, according to Lange, “the pea crop had frozen and there was no work for anybody.”

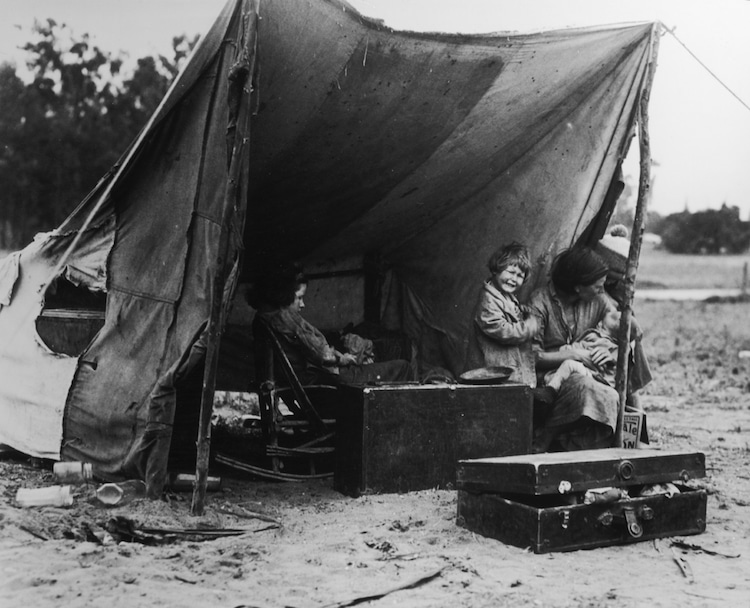

Dorothea Lange, “Drought refugees from Oklahoma at work in the pea fields near Nipomo, California.”

Photo: The Library of Congress

When Lange approached Thompson, she was willing to partake in the photo session with the hope that it would help expose the realities of her dire situation. “There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her,” Lange recalls, “and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.”

While the photographs did raise awareness about the farmers’ struggles and elevated Lange’s professional reputation as a photojournalist, Thompson eventually denied having ever spoken to Lange and expressed regret over posing for her. “I wish she hadn’t taken my picture,” she is quoted in Migrant Mother: How a Photograph Defined the Great Depression. “I can’t get a penny out of it. She didn’t ask my name. She said she wouldn’t sell the pictures. She said she’d send me a copy. She never did.” Unfortunately, this was primarily due to the fact that Lange—a government worker at the time—was federally funded and, thus, her photographs were placed in the public domain.

Thompson (seated) with three of her daughters

Photo: From ‘Dust Bowl Descent’ (1984) by Bill Ganzel

The Photograph Today

Since its 1930s debut, Migrant Mother has been regarded as a symbol of life during the Great Depression and celebrated as Lange’s finest work. While the negative of the image is housed in the Library of Congress (where it is filed under Lange’s original description, Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California), gelatin silver prints of the photograph remain in some of the world’s major museums, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Tate.

See the entire Migrant Mother series below.

Dorothea Lange, ‘Nipomo, Calif. March 1936. Migrant agricultural worker’s family. Seven hungry children and their mother, aged 32. The father is a native Californian.’

Photo: The Library of Congress

Dorothea Lange

Photo: The Dorothea Lange Archive, Oakland Museum

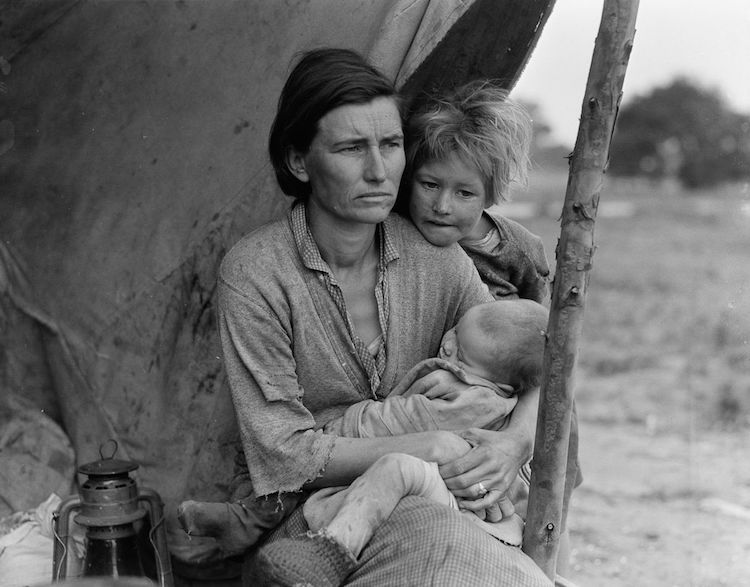

Dorothea Lange, ‘Migrant agricultural worker’s family. Seven children without food. Mother aged 32, father is a native Californian. March 1936.’

Photo: The Library of Congress

Dorothea Lange, ‘Nipomo, Calif. Mar. 1936. Migrant agricultural worker’s family. Seven hungry children. Mother aged 32, the father is a native Californian. Destitute in a pea pickers camp, because of the failure of the early pea crop. These people had just sold their tent in order to buy food. Most of the 2,500 people in this camp were destitute.’

Photo: The Library of Congress

Dorothea Lange, ‘Nipomo, Calif. Mar. 1936. Migrant agricultural worker’s family. Seven hungry children. Mother aged 32. Father is a native Californian.’

Photo: The Library of Congress

This post may contain affiliate links. Please read our disclosure for more info.

Related Articles:

The History of Photojournalism. How Photography Changed the Way We Receive News.

35 Quotes From Master Photographers to Inspire You to Take Great Pictures

Jacob Riis: The Photographer Who Showed “How the Other Half Lives” in 1890s NYC