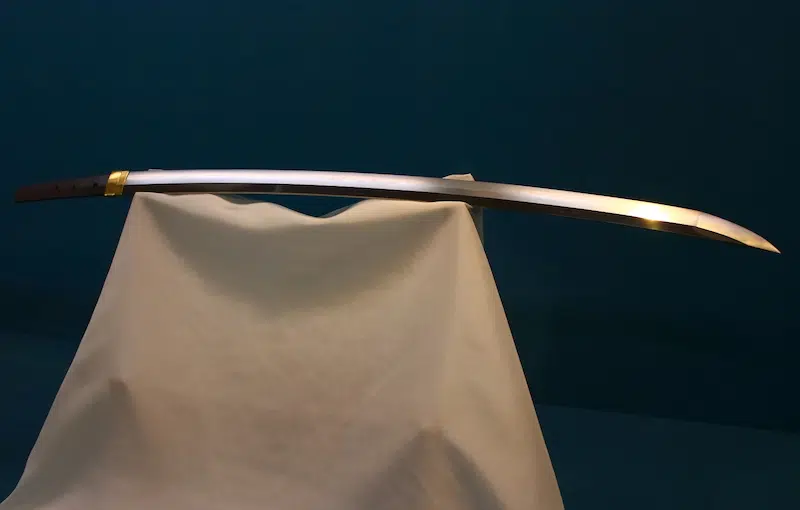

A Japanese katana. (Photo: Kakidai, via Wikimedia Commons, CC 4.0)

From ukiyo-e prints to origami, Japan boasts an astounding range of traditional artforms. One such artform is swordsmithing, a tedious process in which swords such as the legendary katana are made. What renders their construction so labor-intensive is that these swords are, perhaps counterintuitively, composed of sand.

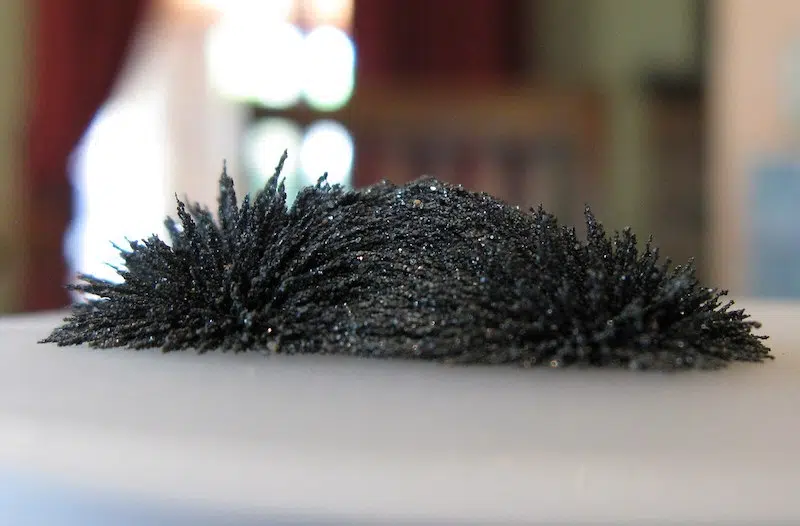

Alongside countries like New Zealand, Indonesia, and the United States, Japan is one of several regions in which iron sand can be found. For centuries, Japanese swordsmiths have smelted iron sand, or tamahagane (“jewel steel”), with charcoal in large clay furnaces known as tataras to create katanas. During this stage, swordsmiths must carefully monitor the temperature of the tatara, while simultaneously ensuring there is a sufficient amount of both charcoal and iron sand inside the furnace.

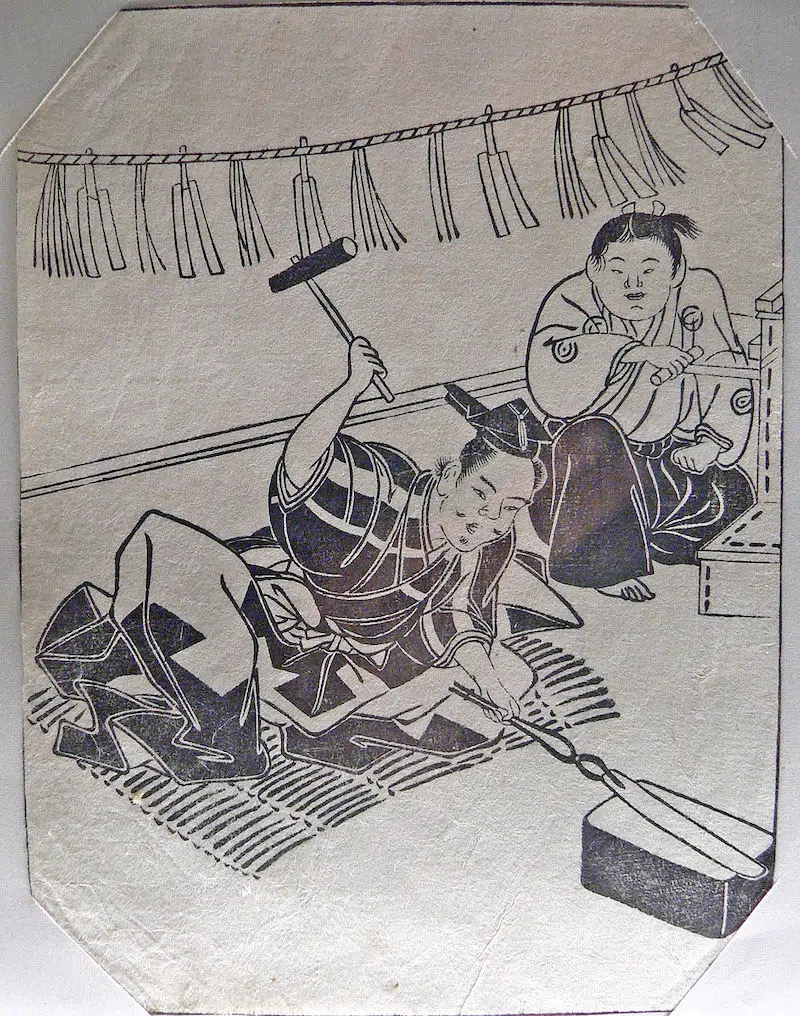

This smelting phase can last for days, requiring supervision without any interruptions. For this reason, the art of swordsmithing has historically been reserved for those with tremendous patience, dexterity, and mastery over the materials at hand.

“The forging of a Japanese sword is a subtle and careful process,” Edward Hunter writes in an essay for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “[It’s] an art that has developed over the centuries as much in response to stylistic and aesthetic considerations as to technical improvements.”

Once the smelting process is complete, the best tamahagane pieces are selected from the tatara. A swordsmith heats, hammers, and folds the steel repeatedly, further homogenizing the carbon and iron while drawing out any remaining imperfections or impurities from the materials. The folding also produces the patterns, or jihada, for which katana blades are known.

Preparing the sword’s edge is often considered the most important yet challenging aspect of swordsmithing. The blade is first coated with yakibatsuchi, a mixture of water, clay, and ash, among other ingredients, and taken into a forge room lit only by glowing coals. Here, the swordsmith carefully heats the blade.

“As the temperature rises, crystal structures within the metal begin to change. The smith carefully observes the color of the glowing blade, and when the critical temperature is reached, the sword is quickly quenched in a trough of water,” Hunter explains.

While heating the blade, the steel changes to austenite, and once quenched, the austenite changes to martensite, the hardest type of steel. Wherever yakibatsuchi was applied, the blade retains a level of flexibility and softness, which is what ultimately creates the ideal katana sword. Finally, blades are then polished using water stones, generating a finer and sharper finish.

The method of smithing katana swords has largely gone unchanged, and given its highly specialized nature, it should come as no surprise that these swords have long been considered the souls of samurai. Perhaps, too, this belief has something to do with the magic of watching soft sand transform into razor-sharp yet beautiful weapons.

For centuries, Japanese swordsmiths have transformed iron sand into katanas.

Iron sand from Four Peaks mountain near Phoenix, Arizona, attracted to a magnet. (Photo: Jlahorn, via Wikimedia Commons, CC 3.0)

Swordsmiths smelt iron sand in clay furnaces, a labor-intensive process that can often take days to complete.

Katana mountings decorated with maki-e lacquer in the 1800s. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, via Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0)

Blades are then folded over to draw out any imperfections, after which their edges are prepared.

Japanese sword blade and sharpening stone and water bucket at 2008 Cherry Blossom Festival, Seattle Center, Seattle, Washington. (Photo: Joe Mabel, via Wikimedia Commons, GNU Free Documentation License)

Often considered the soul of a samurai, katanas are created from an almost magical process, creating a razor-sharp weapon through soft sand.

Blacksmith scene, print from a Edo period book. (Photo: Rama, via Wikimedia Commons, CC 2.0)

Sources: The Japanese Blade: Technology and Manufacture; Secrets of the Samurai Sword: Making a Masterpiece; How is a traditional samurai sword made?; How Japanese Masters Turn Sand Into Swords

Related Articles:

Artist Spends 3 Months Planning and Folding Origami Samurai From a Single Sheet of Paper

Legendary 1,000-Year-Old Katana Still Looks as Flawless as When It Was First Constructed

Conceptual ‘Casa Katana’ Is an Angular Abode Inspired by the Japanese Sword