World Memorial to the Pandemic (Design by Gómez Platero Architecture & Urbanism)

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

Uruguayan architect Gomez Platero has released a series of conceptual renderings of a mass memorial for the victims of COVID-19. Titled World Memorial to the Pandemic, the design features a circular concrete structure along the oceanside of an unspecified site. The minimal plane is disrupted by a singular void cut out of the center, allowing visitors to look inward at the water below, or outwards towards the horizon.

Platero believes this design was necessary to imagine a built space where people could remember, reflect, and mourn. “Monuments, too, mark our shared cultural and emotional milestones,” he says. “By creating a memorial capable of activating senses and memories in this way, we can remind our visitors—as the pandemic has—that we as human beings are subordinate to nature and not the other way around.”

World Memorial to the Pandemic (Design by Gómez Platero Architecture & Urbanism)

Monuments dedicated to the dead have been around for millennia, so this idea of building a memorial isn’t new. But while this particular design is in its early stages of being conceptualized, there are many monuments across the world that are being torn down. In 2020, in particular, there has been an uprising of concerns over confederate statues in the United States that celebrate individuals with complicated and increasingly problematic histories. In order to understand why the demand to take these monuments down is important and what this means for the future, we have to look back and recognize why we have monuments in the first place.

Why Do We Have Monuments?

Monuments are fundamental to the human experience—they allow us to remember our past, express the values of our culture, and sometimes to even oppress with a constant reminder of a difficult history or societal expectation. Aside from burial sites and temples, some of the oldest structures in the world are memorials to the dead. Monuments or commemorative statues are types of memorials that often pay homage to individuals. The statue is often built in the likeness of the person it’s commemorating. Each monument serves as a physical representation of a memory that is celebrated. This can be especially problematic with time, as what was once celebrated is eventually reexamined, criticized, and potentially vilified.

How Confederate Statues Are Making Architects Rethink Monuments

Nathan Bedford Forrest Monument (Photo: Stock Photos from Suzanne C. Grim/Shutterstock)

“All wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.” These words were written by Viet Thanh Nguyen, author of The Sympathizer, referring to the Vietnam War. At a Harvard Graduate School of Design event titled “On Monuments: Place, Time, and Memory,” past Harvard President Drew Gilpin Faust shared her thoughts on this theory in regard to the American Civil War. She said that, in many ways, though the North won the battle, the South has continued the fight in memory. This is demonstrated by the survival of the confederate flag long after the confederacy’s four-year-long existence and the emergence of confederate statues that spiked 50 years after the war’s end.

This story may be a meaningful example to understand how monuments have the power to oppress, and how the intention of a monument is far more relevant than the figure or form they depict. In today’s political climate, the importance of remembering our past and acknowledging the shifting values of our society has become increasingly important. How do we preserve current monuments that no longer meet our values, and should we preserve them at all? Is intention important when considering the removal of monuments? Do monuments need to be more abstract to stand the test of time? Do memorials need to do something, do we expect to engage with these spaces to feel connected to our past? These are all valid questions and concerns that architects are now addressing in their designs. There is a clear shift in the way monuments are now being designed.

Nathan Bedford Forrest Monument

Nathan Bedford Forrest Monument (Photo: Stock Photos from L. Kragt Bakker/Shutterstock)

A bronze statue of General Nathan Bedford Forrest riding his horse while dressed in the Confederate Army Uniform was installed in Forrest Park in Memphis, Tennessee. Forrest and his wife were dug up from their graves nearly 30 years after their deaths and reburied in the park.

So why was a slave trader and a leader of the Ku Klux Klan commemorated 40 years after a lost war? Even though the Civil War ended in 1865, a majority of Confederate monuments were built between 1890 and 1950, during the Jim Crow era. The largest amount of these statues were installed during 1900-1920. The Forrest Monument coincides with this time frame, having been built in 1905. Though earlier monuments were typically installed in cemeteries, this new era of Confederate monuments placed them in main public spaces and often in front of city buildings.

A graphic map created through data from the Southern Poverty Law Center reveals an important pattern. An increase in Confederate monuments in the 1900s, and the erection of the Forrest Monument, happened just as Southern states attempted to legally segregate society.

What Will Future Monuments Look Like?

Regardless of individual feelings on the controversial monuments scattered across the world, future designers of monuments must contend with the fact that what is sacred today, may not be sacred tomorrow.

Modern iconic memorials tend to be pieces of architecture that allow us to connect with history in physical ways. With the knowledge that monuments and memorials can oppress, inspire, and heal, designers have a responsibility to craft a narrative for an entire community—and in cases of significant monuments, the entire world.

Scroll down for two more examples of modern monuments (in addition to Platero’s COVID-19 victims memorial) that memorialize lives lost.

Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe

Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (Photo: Stock Photos from D.Bond/Shutterstock)

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe was designed by Peter Eisenman and features 2,711 concrete slabs aggregated across a massive landscape. The sculpture park creates a wave-like form as the slabs of different heights interact with the landscape. It is meant to be experienced as a procession that is different for each visitor.

It is open at all times of days, and from all endpoints. It is designed to be purposely abstract and non-prescriptive so that visitors can experience it as they need to. Once their procession is complete, an underground area includes the names of three million Jewish victims of the Holocaust.

Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (Photo: Stock Photos from D.Bond/Shutterstock)

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice

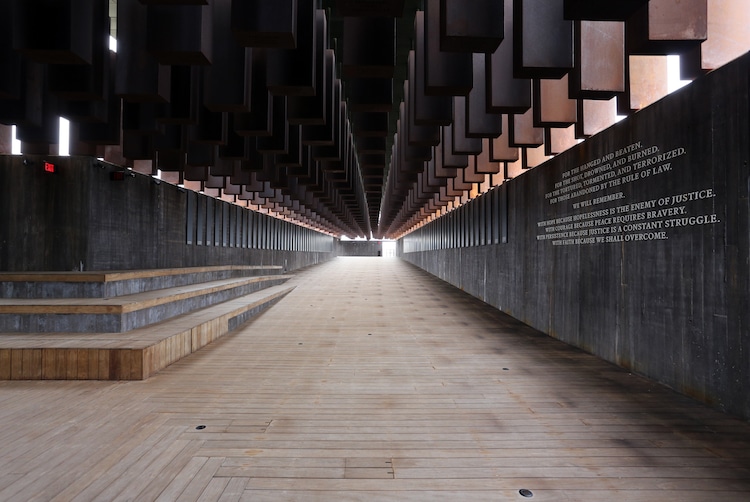

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice (Photo: Stock Photos from Katherine Welles/Shutterstock)

Designed by the Equal Justice Initiative and MASS Design Group, The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is a structure in Montgomery, Alabama that acts as the first memorial for victims of lynching in the United States. Both the memorial and the nearby Legacy Museum are the result of an interdisciplinary planning process led by EJI’s Executive Director Bryan Stevenson. The National Memorial spreads across six acres of land and is dotted with sculptures and art that “contextualizes racial terror” while providing a space for true engagement. In the memorial square built in collaboration with MASS Design Group, each Corten steel block symbolizes a county in the U.S. that has lynched a Black person. The design creates a moving and overwhelming experience for visitors as the sheer number of blocks—about 800—hang overhead.

EJI explains, “The memorial is more than a static monument. It is EJI’s hope that the National Memorial inspires communities across the nation to enter an era of truth-telling about racial injustice and their own local histories.”

Though it may be possible to summarize the characteristics that seem to define modern monuments, the way we remember and the way that we grieve is a constantly changing and intangible experience—one that designers will continue to honor in the built environment.

Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (Photo: Stock Photos from Anton Havelaar/Shutterstock)

Related Articles:

Syrian Refugees Recreate Destroyed Monuments to Always Remember Their Culturally Rich Architecture

Powerful BLM Video Projections Help Reclaim Controversial Robert E. Lee Monument [Interview]

Monumental Hands Reach Across Venice Canal as a Symbol of Unity

Moving COVID-19 Memorial in Uruguay Pays Tribute to Victims of the Pandemic