A camera obscura device. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Before the invention of the photographic camera, transferring a real-life image onto paper or another flat surface was no easy feat. Renaissance artist and inventor Leonardo da Vinci first described a mechanism that would make drawing in perfect perspective much easier to achieve, something that would later be known as camera obscura. Rather than meticulously measuring out the lengths and angles of a subject or scene, camera obscura offers a shortcut. The controversial invention allowed artists to simply trace lines and shapes from a protected image onto their canvas.

What Is Camera Obscura?

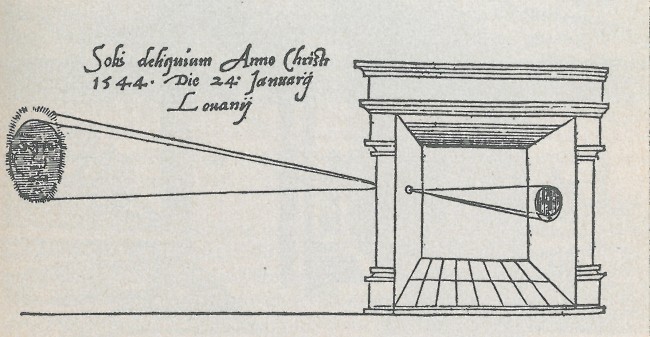

First published illustration of camera obscura in Gemma Frisius’ book “De Radio Astronomica et Geometrica,” 1545 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Camera obscura (meaning “dark room” in Latin) is a box-shaped device used as an aid for drawing or entertainment. Also referred to as a pinhole image, it lets light in through a small opening on one side and projects a reversed and inverted image on the other.

How It Works

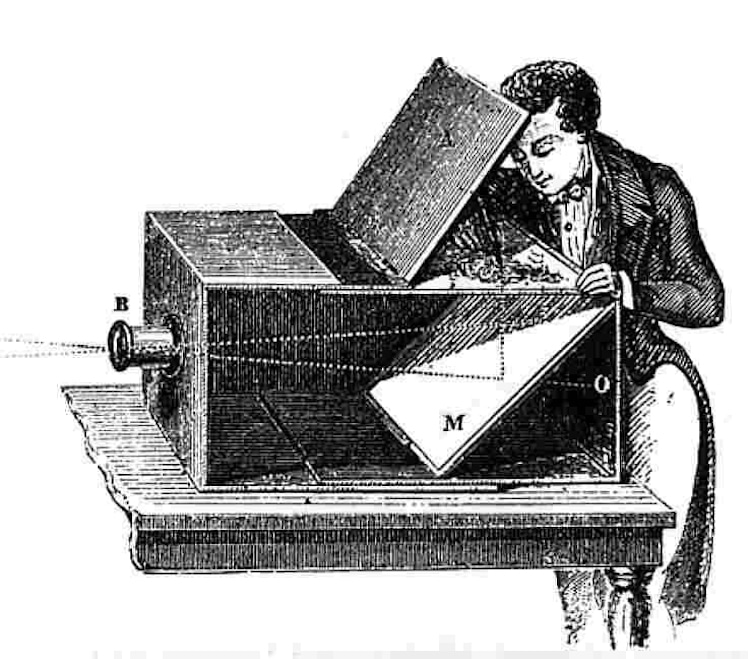

The camera obscura principle, illustrated by James Ayscough in “A short account of the eye and nature of vision,” 1755 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

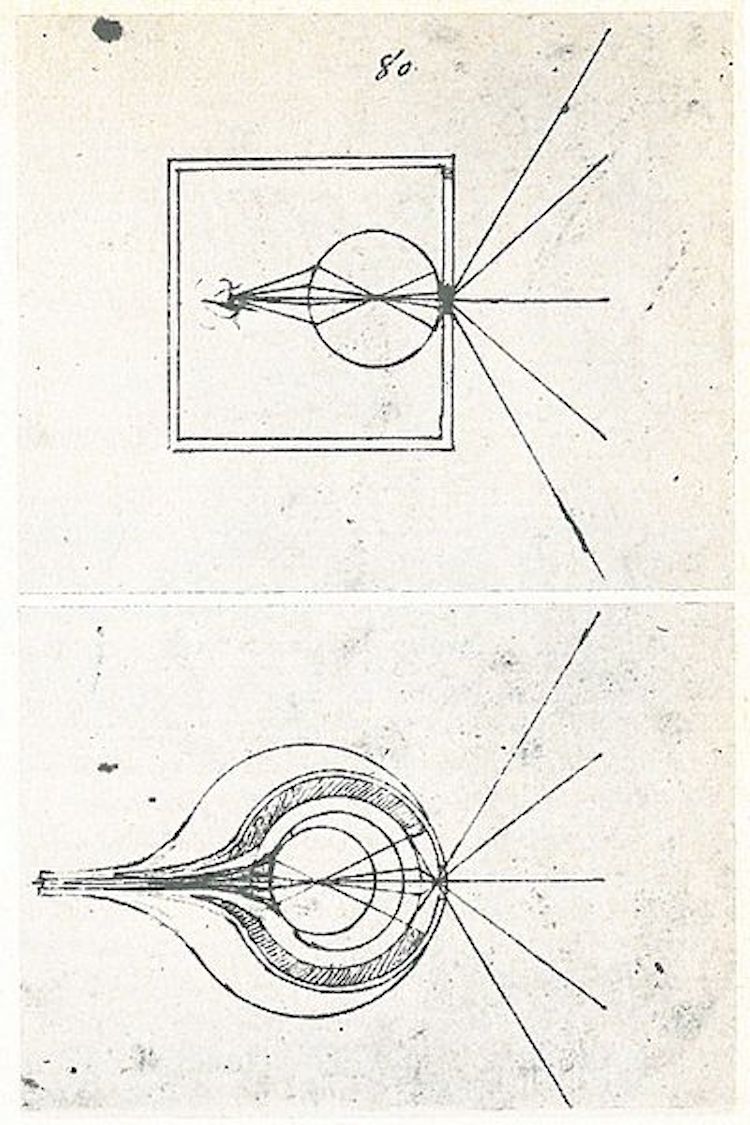

As the name suggests, many historical camera obscura experiments were performed in dark rooms. The surroundings of the projected image have to be relatively dark for the image to be clear. The human eye works a lot like the camera obscura; both have an opening (pupil), a biconvex lens for refracting light, and a surface where the image is formed (retina).

Early camera obscura devices were large and often installed inside entire rooms or tents. Later, portable versions made from wooden boxes often had a lens instead of a pinhole, allowing users to adjust the focus. Some camera obscura boxes also featured an angled mirror, allowing the image to be projected the right way up.

The History of Camera Obscura

A 19th-century illustration of a camera obscura box with mirror, with an upright projected image at the top (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The earliest written record of the camera obscura theory can be found in the studies of Chinese philosopher and the founder of Mohism, Mozi (470 to 390 BCE). He recorded that the image in a camera obscura is flipped upside down because light travels in straight lines from its source.

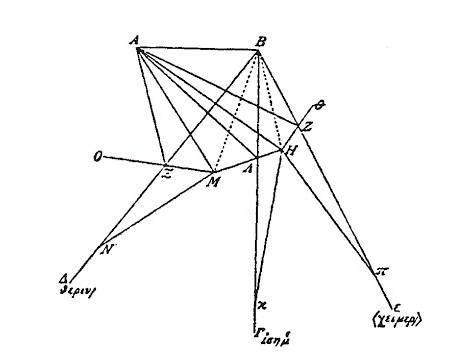

Anthemius of Tralles’s diagram of light-rays reflected with plane mirror through hole (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

During the 4th century, Greek philosopher Aristotle noticed that sunlight passing through gaps between leaves projects an image of an eclipsed sun on the ground. The phenomenon was also noted by 6th-century Greek mathematician and co-architect of the Hagia Sophia, Anthemius of Tralles, who used a type of camera obscura in his experiments. During the 9th century, Arab philosopher, mathematician, physician, and musician Al-Kindi also experimented with light and a pinhole.

Familiar with these early studies, Leonardo da Vinci published the first clear description of the camera obscura in Codex Atlanticus (1502), a 12-volume bound set of his drawings and writings where he also talked about other inventions such as flying machines and musical instruments. He wrote (translated from Latin):

If the facade of a building, or a place, or a landscape is illuminated by the sun and a small hole is drilled in the wall of a room in a building facing this, which is not directly lighted by the sun, then all objects illuminated by the sun will send their images through this aperture and will appear, upside down, on the wall facing the hole. You will catch these pictures on a piece of white paper, which placed vertically in the room not far from that opening, and you will see all the above-mentioned objects on this paper in their natural shapes or colors, but they will appear smaller and upside down, on account of crossing of the rays at that aperture. If these pictures originate from a place that is illuminated by the sun, they will appear colored on the paper exactly as they are. The paper should be very thin and must be viewed from the back.

Over the years, Da Vinci drew around 270 diagrams of camera obscura devices in his sketchbooks.

A drawing comparing the human eye to a camera obscura from Leonardo da Vinci’s “Codex Atlanticus,” 1490–1495 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

During the 15th century, other artists began to see the potential of using the camera obscura as a drawing aid. However, using the device sparked controversy, as many viewed the tracing method as cheating.

Johannes Vermeer and Camera Obscura

Although there is no documented evidence to prove it, art historians have suggested that 17th-century Dutch master Johannes Vermeer used the camera obscura as an aid to create his paintings. The theory is based on studies of the artworks themselves. Beneath the surface of his paintings, there are no signs that he made any corrections to his layouts as he worked. Instead, Vermeer created a shadowy image outlining the scene before painting, perhaps based on a projected image.

Johannes Vermeer, “Officer and Laughing Girl,” 1657 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The first person to publicly propose the possibility that Vermeer used a camera obscura was American artist Joseph Pennell. In 1891, he noticed that the man in the foreground of Vermeer’s Officer and Laughing Girl (1657) was shown nearly twice as large as the girl he sat facing—just as the scene would appear in a photograph.

Even if Vermeer did use the camera obscura to achieve photographic perspective, his talent shouldn’t be diminished. Painter and writer of Traces of Vermeer (2017), Jane Jelley, writes, “The image from the camera obscura is merely a projection. To capture and transfer this to canvas requires skill, judgment, and time; and its product can only ever be part of the process of making a painting. We can never know if Vermeer worked this way, but we should remember that this is not a mindless process and not a shortcut to success.”

How to Make Your Own Camera Obscura

Despite its long history, camera obscuras haven’t completely fallen out of fashion. Some contemporary photographers and artists continue to utilize these devices as visual aids.

Additionally, because of their simple design, camera obscuras make fun DIY projects for children and adults alike. All you need to get started is some cardboard, a magnifying glass, a paper bag, some tape, and glue.

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

How the Development of the Camera Changed Our World

Get an “Instant” History of How Polaroid Revolutionized Photography

Girl with a Pearl Earring: Unraveling the Mysterious Masterpiece of the Dutch Golden Age