Botticelli, “Primavera,” ca. c. 1477–1482 (Photo: Google Arts & Culture via Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Florentine artist Sandro Botticelli is credited for his contributions to the Italian Renaissance. Widely considered one of the most prolific painters of the 15th century, he is known for his large-scale paintings of mythological subject matter, including Primavera, an allegorical celebration of spring.

This piece is one of the most important Early Renaissance works. Housed by Florence’s famed Uffizi Gallery, it continues to attract viewers with its classical symbolism, elaborate composition, and delicate attention to detail.

In order to grasp its enduring significance, it’s important to first understand the context in which it was commissioned and created.

Context

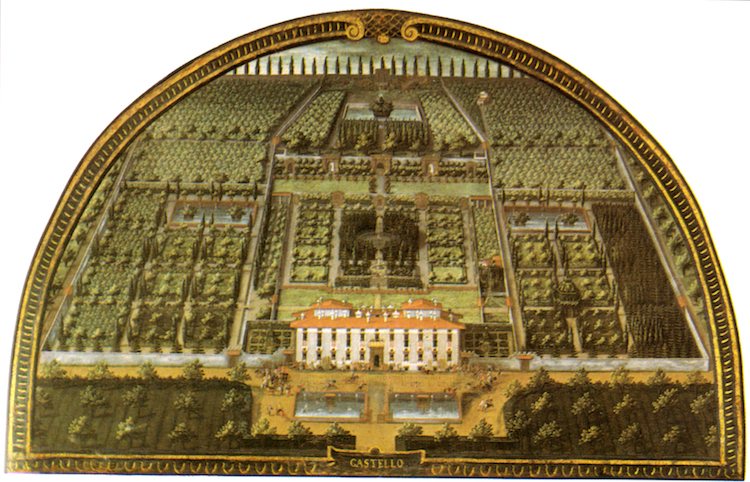

Botticelli painted Primavera around 1480. While its exact origins are debated, it is believed to have been commissioned by Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici—a cousin of Florence’s ruling family—as a gift for his new bride. During this time, art was typically commissioned for Catholic churches and civic buildings. However, Primavera was created for Di Pierfrancesco’s private estate, the Villa di Castello.

Giusto Utens, “Lunette of Villa di Castello as it appeared in 1599” (Photo via Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)\

Along with The Birth of Venus (another larger-than-life painting), Boticelli painted Primavera after returning to Florence from Rome, where he was hired to create frescoes in the Sistine Chapel. During this time, he began to turn his attention away Roman Catholic iconography and towards scenes from Greek and Roman mythology.

This humanist interest in ancient allegories culminated in The Birth of Venus and Primavera—two tempera paintings starring Venus, the Roman goddess associated with love and beauty.

Subject Matter

Venus is featured in the center of Primavera. Clad in typical 15th-century Florence attire, she stands in an arch beneath her son, Cupid, who aims his bow and arrow toward the Three Graces. In mythology, this trio of sisters often represents pleasure, chastity, and beauty, though the specific identities of Botticelli’s figures are not clear.

Detail of Venus and Cupid

Detail of the Three Graces

To the left of the Three Graces, Mercury—the Roman god of May—uses his caduceus, or staff, to nudge away a cluster of small, grey clouds. Known as the messenger of the gods, he is shown wearing his signature helmet and winged sandals.

Detail of Mercury

On the right-hand side of the composition, Zephyr, the Greek god of the west wind, grabs Chloris, a nymph associated with flowers. In mythology, she transforms into Flora, the goddess of spring, who is depicted to the left of the pair.

Detail of Flora, Zephyr, and Chloris

Fittingly, this springtime scene is set in a mythical forest. Botticelli incorporated roughly 500 identifiable plant species in the scene, including nearly 200 types of flowers.

Detail of the flowers