Confiscated by Britta Jaschinski. National Wildlife Property Repository, Colorado, USA. Grand Prize Winner .

Nearly 6,000 images were submitted to the fourth annual BigPicture Natural World Photography Competition, which highlights the best nature and wildlife photography around the world. The recently announced winners will have their images on display at the California Academy of Sciences for three months starting on July 28, 2017.

Photographers from 63 different countries participated in the contest, using their lens to address important aspects of today’s pressing environmental issues. Grand prize winner Britta Jaschinski uses her work to raise awareness of animal suffering around the world. Her image Confiscated shows two confiscated stools made from elephant feet that were in storage at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife repository near Denver, Colorado. While Americans can sometimes feel that these cruelties are a reality far from home, the stools are just two of the 1.3 million confiscated animal products housed in the repository.

Jaschinski’s stark, straightforward image is a reminder that even with increased bans on products made from endangered species, a startling amount still makes their way into the black market. Recently, researchers radiocarbon dated ivory seized from 2002 to 2014, sadly proving that most samples come from recent kills.

“Trolleys are used to move the confiscated items around the warehouse,” Jaschinski shares. “I placed the body parts on this backdrop to give some dignity to the objects and pay respect to the animals that loose [sic] their lives in the name of status, greed, and superstition.” Through her work, Jaschinski, as well as the other finalists, give necessary reminders of what work still needs to be done in order to safeguard our wildlife and environment.

These images originally appeared on bioGraphic, an online magazine about science and sustainability and the official media sponsor for the California Academy of Sciences’ BigPicture Natural World Photography Competition.

The BigPicture Natural World Photography highlights the best nature and wildlife photography around the world. These are some of the winners and finalists from the competition, which had over 6,000 entries.

The More the Merrier by Alexandre Bonnefoy. Shōdoshima Island, Japan. Finalist Terrestrial Wildlife.

When temperatures drop, macaques often huddle together to pool their body heat, forming what’s known as a saru dango, or “monkey dumpling.” This behavior is common among the 23 species of macaques, all of which form complex matriarchal societies. It is especially important for Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata), which live in colder climates than any other primate, aside from humans. On frigid days, their need for warmth clearly outweighs their desire for personal space.

Roundup at Revillagigedo by Ralph Pace. Revillagigedo Archipelago, Mexico. Finalist Aquatic Life.

The remote Revillagigedo Islands off the west coast of Mexico are actually the four highest peaks of a mostly submerged volcanic mountain range. In the surrounding marine sanctuary, cool waters from the North Pacific mix with the warm Northern Equatorial Current. This nutrient- and plankton-rich convergence attracts a diverse array of sea life—and the protections mandated by the sanctuary help to sustain an unusually healthy marine ecosystem. In this photograph, more than a thousand top predators, including dusky sharks (Carcharhinus obscurus), yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares), and Galápagos sharks (Carcharhinus galapagensis) work in unison to round up a shared meal of chub and other baitfish.

Ecosystem by Marcio Cabral. Emas National Park, Brazil. Winner Terrestrial Wildlife.

As if to compete with the brilliance of the night sky, a towering termite mound puts on its own light show above the subdued landscape of Western Brazil. This effect is produced by one of the mound’s residents: larvae of the Brazilian click beetle (Pyrearinus termitilluminans). While the termites construct the mound, click beetles burrow into the porous earthen structure and lay their eggs inside. Like fireflies, click beetle larvae produce their characteristic green glow via a chemical reaction within their tissues. Rather than using the light to attract a mate, however, the larvae use their glow to attract prey: winged termites they’ll catch and eat as the insects emerge from the mound during the first weeks of the rainy season.

Kamokuna Lava Firehose 25 by Jon Cornforth. Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park, Hawai’i, USA. Winner Landscapes, Waterscapes, and Flora.

This past January, a steady stream of lava, called a firehose, suddenly gushed from an underground lava tube at the base of Hawai’i’s Kilauea volcano and spilled into the Pacific Ocean. As the molten rock met the cooler seawater, steam, sand, and chunks of cooled lava were thrown explosively into the air. The impact of these continual bursts of energy eventually created a crack in the 90-foot seacliff, which expanded over the course of a week until a section of the cliff broke off entirely and sloughed into the sea.

Fearless in the Flames by Kallol Mukherjee. Singur, West Bengal, India. Winged Life Finalist

When farmers in West Bengal finish their harvest of wheat or rice, they often burn the straw and stubble that’s left behind. It’s a quick–if destructive and banned—way to clear the field and return some of the crop’s nutrients to the soil in preparation for the next season’s planting. The practice is also a boon to local birds. As insects flee the flames, birds like these black drongos (Dicrurus macrocercus) swoop in to take advantage of the bounty.

The Salmon Catchers by Peter Mather. Yukon River watershed, Canada. Finalist Terrestrial Wildlife.

To capture this view of a mother grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis) and her cub, photographer Peter Mather set up a camera trap on a log that he knew the bears tended to traverse while fishing for salmon. Packed with both protein and fat, salmon provide grizzlies with a critical source of energy and nutrients during the spawning season. However, the fish can also carry high levels of environmental toxins, such as mercury, that put the bears at risk. Because mercury accumulates in the tissues of organisms and is passed along the food chain, top predators like grizzlies tend to be exposed to higher concentrations of the toxic metal. Indeed, scientists have found that some 70 percent of grizzly bears sampled along the coast of British Columbia over the past decade contained mercury levels above what is considered safe.

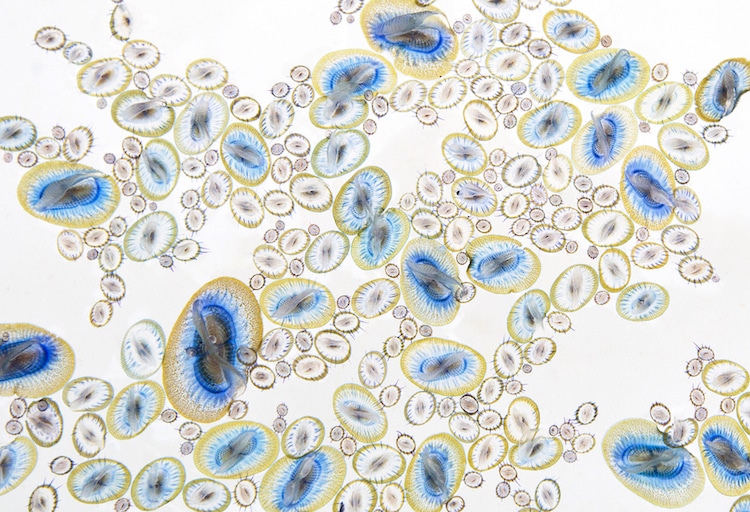

Sea Jewels by Jodi Frediani. Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, California, USA. Winner Art of Nature.

These beauties may appear to be single-celled organisms viewed under a microscope, but you’re actually looking at a bucket filled with dozens of by-the-wind sailors (Velella velella). Each sailor—measuring up to three inches long—is a colony of individual polyps that feed on plankton, reproduce, and defend the colony. These close relatives of jellyfish float on the surface of the ocean, their translucent triangular sails providing mobility. But like other sailors, they travel at the mercy of the wind, and occasionally end up stranded en masse along Pacific Coast beaches.

‘Pandas Gone Wild’ by Ami Vitale. Wolong National Nature Reserve, Sichuan Province, China. Winner Human/Nature.

At the Hetaoping Research and Conservation Center in China’s Wolong Reserve, captive-bred giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) have been raised with the hope of one day reintroducing them to the wild. To prevent young pandas from imprinting on and becoming attached to their human caregivers, the center’s staff wear costumes that mimic the animals’ characteristic black and white pattern. That pattern, which scientists have puzzled over for decades, is now thought to be an evolutionary compromise that allows pandas to blend into both snowy backgrounds in the winter and shadowy forests in the summer.

Snow Globe by Denise Ippolito. Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge, New Mexico, USA. Winner Winged Life

Since the 1960s, North American populations of snow geese (Chen caerulescens) have exploded an estimated thirteen-fold, in part because of the sprawling fields of grain that have cropped up along their migration route over the past 60 years. In Canada, the species has been officially declared overabundant, largely due to its impact on sensitive Arctic habitats. Descending in vast flocks, the geese leave a wake of mowed-down plants and exposed ground that can take decades to recover. The results can be devastating for other species, such as the endangered rufa red knot (Calidris canutus rufa), that rely on this vegetation for foraging and nesting habitat.

Synchronized Sleepers by Franco Banfi. Commonwealth of Dominica, Caribbean Sea. Finalist Human/Nature.

Photographer Franco Banfi and his fellow divers were following this pod of sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) when the giants suddenly seemed to fall into a vertical slumber. This phenomenon was first studied in 2008, when a team of biologists from the UK and Japan inadvertently drifted into a group of non-responsive sperm whales floating just below the surface. Baffled by the behavior, the scientists analyzed data from tagged whales and discovered that these massive marine mammals spend about 7 percent of their time taking short (6- to 24-minute) rests in this shallow vertical position. Scientists think these brief naps may, in fact, be the only time the whales sleep.

Mantis Mom by Filippo Borghi. Lembeh Strait, Indonesia. Winner Aquatic Life.

Surrounded by black volcanic sands, a peacock mantis shrimp (Odontodactylus scyllarus) stands guard over her ribbon-like mass of fertilized eggs. The folds of this portable, flexible structure—held together with an adhesive produced by the mother—provide ample surface area for gas exchange between the egg membranes and the surrounding environment. The female cleans and aerates the developing eggs with the same appendages she typically uses to handle prey. With her limbs more than full caring for her brood, the female won’t eat until the eggs hatch and the larvae disperse.

BigPicture Natural World Photography Competition: Website | Facebook | Instagram

My Modern Met granted permission to use images by the BigPicture Natural World Photography Competition.

Related Articles:

Interview: Photojournalist Follows Siberia’s Risky New Gold Rush by Shadowing Mammoth Tusk Hunters

10 Fantastic Finalists of the World Wildlife Day Photography Competition

TripAdvisor Discontinues Ticket Sales to Anywhere with Attractions That Hurt Animals

Amazing Winners of the 2016 National Geographic Nature Photographer of the Year Contest

Number of Poached Rhinos in South Africa Decreases For the First Time in Over a Decade