Portrait of Benjamin Franklin by David Martin, 1767 (Photo: The White House Historical Association, via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain).

Among the Founding Fathers of the United States, Benjamin Franklin was unique: he was a polymath, finding prominence as a diplomat, printer, inventor, philosopher, and author during his lifetime. Even so, he failed math twice.

When he was eight years old, Franklin was enrolled in a Boston grammar school. By 1715, however, Franklin’s father withdrew him from his studies and instead sent him to a school specifically for learning writing and math. While there, Franklin claimed to have “acquired fair writing pretty soon, but I failed in arithmetic, and made no progress in it.”

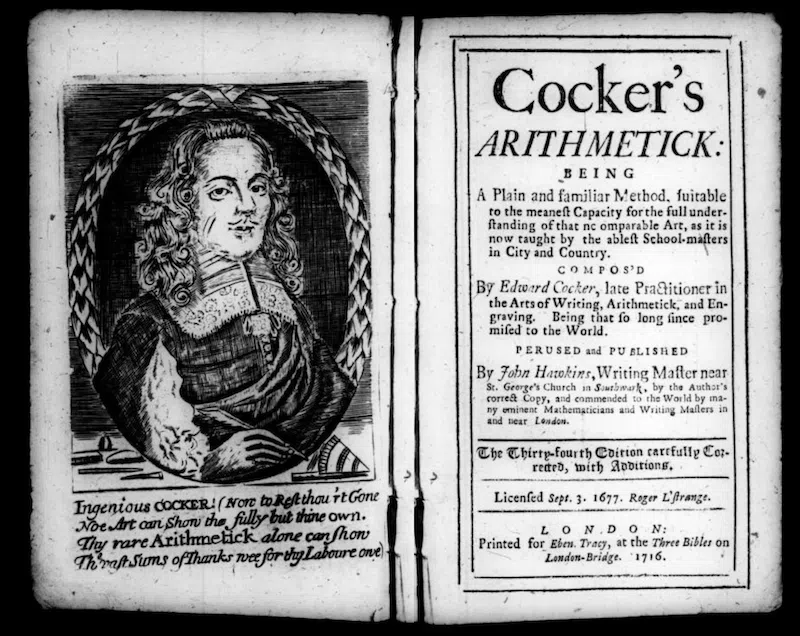

What Franklin eventually turned to was Cocker’s Arithmetick. The book, published posthumously in 1678, compiled the notes of Edward Cocker, a London-based teacher. The lessons contained within ranged from addition and subtraction to multiplication and division, alongside sets of rules intended to be memorized by its students. It also covered economic subjects such as pre-decimal British currency and arithmetic for business use.

Modern readers are hardly eager to flip through a textbook, but Cocker’s Arithmetick was a household name during the 17th and 18th centuries. Given its affordable price—it cost one shilling—and portable size—it was about the size of a smartphone—the book became an instant bestseller. Within its first year of publication alone, it received a second and third impression.

Cocker’s Arithmetick gained such popularity that a new edition of the book was reissued nearly every year until the mid-18th century. It even inspired the phrase “according to Cocker,” meaning “quite correct.”

How, exactly, the British mainstay made its way into Franklin’s hands around 1722 is unclear, especially since he wouldn’t visit the country until 1724. Regardless, the textbook offered Franklin the crucial opportunity not only to improve but also to master his mathematical skills.

“Being on some occasion made ashamed of my ignorance in figures, which I had twice failed in learning when at school, I took Cocker’s book of arithmetic,” Franklin wrote in his autobiography. “[I] went through the whole by myself with great ease.”

Today, Franklin is remembered as one of America’s most ingenious figures, and his struggles with math are often either forgotten or simply not known. Still, his perseverance and ultimate triumph speak to the enterprising spirit that would come to define the country he helped found.

Despite being a renowned polymath and Founding Father of the United States, Benjamin Franklin failed math twice while in school.

A scene from Benjamin Franklin’s early life (Photo: Internet Archive, via Wikimedia Commons).

Franklin turned to the popular 17th-century textbook Cocker’s Arithmetick, which was a household staple and immensely popular given its price and portability.

Cocker’s Arithmetick (Photo: Internet Archive).

Cocker’s Arithmetick distilled basic math, business arithmetic, and currency information and was reissued over 130 times.

Portrait of Edward Cocker by Richard Gaywood (Photo: National Portrait Gallery, via Wikimedia Commons).

Sources: Benjamin Franklin: Autobiography, Part One (written in 1771); “From a Child I Was Fond of Reading”: Benjamin Franklin Becomes a Printer; Edward Cocker: English mathematician; After Failing Math Twice, a Young Benjamin Franklin Turned to This Popular 17th-Century Textbook

Related Articles:

Why 1,200 Bone Pieces From 28 People Were Found in Benjamin Franklin’s Basement

This 16th-Century Manual Is the First English Guide on ’The Art of Swimming’

Descendants of the U.S. Founding Fathers Recreate Iconic Painting 241 Years Later

29 Bottles of Preserved Fruit From the 18th Century Discovered at George Washington’s Estate