For centuries, painters have adopted the art studio as subject matter. Popular among Old Masters and modern artists alike, this iconography can offer an intimate glimpse into an individual’s creative practice.

While many artists have given viewers a painterly peek into their workspaces, certain set-ups stand out from the rest. Here, we explore these unique studios through the eyes of the artists who worked in them.

Rembrandt’s Simple Studio

Rembrandt, ‘The Artist in his Studio’ (ca 1626-1628) (Photo via Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

During the Dutch Golden Age, artists shifted their focus from religious iconography to secular subjects. Painter, printmaker, and draughtsman Rembrandt was at the forefront of this transition, culminating in a collection of narrative art, landscapes, and—most famously—roughly 100 self-portraits.

While most of Rembrandt’s self-portrayals convey a focus on the artist’s expressive face, The Artist in his Studio also emphasizes the setting: his austere studio. With hardly any furniture or decoration, the studio is devoid of distraction, making it a perfect place for quiet contemplation and study. Furthermore, the prominence of the in-progress painting in The Artist in his Studio emphasizes the simple nature of Rembrandt’s workshop, where the dedicated artist would spend most of his time.

Courbet’s Allegorical Atelier

Gustave Courbet, ‘The Painter’s Studio: A real allegory summing up seven years of my artistic and moral life‘ (1855) (Photo via Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

While Rembrandt’s painting offers a straightforward glimpse into the simplicity of his workspace, Gustave Courbet’s showcases the artist’s interest in the studio as a symbol. In The Painter’s Studio: A real allegory summing up seven years of my artistic and moral life, Courbet shows “society at its best, its worst, and its average.”

On the left side of the canvas are everyday people, contrasted by a group of elites on the right. In the center is Courbet, shown working on a large-scale painting as a nude woman—believed to represent the tradition of academic art—and young boy attentively watch.

While it is unlikely that this situation would unfold in real life, the painting illustrates the importance of Courbet’s studio—a place where, according to the artist, “the world comes to be painted.”

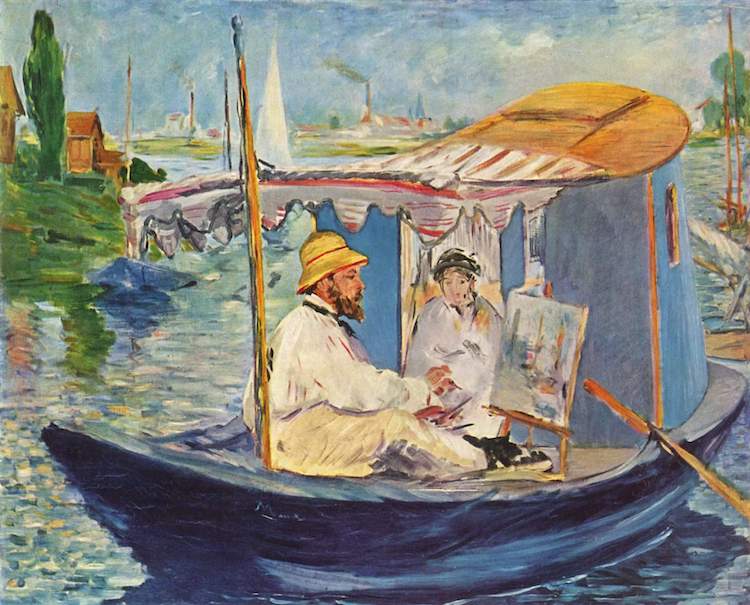

Monet’s Studio Boat

Édouard Manet, ‘Claude Monet in Argenteuil’ (1874) (Photo via Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

With an interest in capturing fleeting impressions of nature, many Impressionist artists abandoned conventional studios in favor of painting outside, or en plain air. Claude Monet got the best of both worlds with his studio boat, a floating atelier he used while living in Argenteuil, France.

In addition to enabling the artist to easily travel around the Seine, the studio boat gave him the opportunity to closely study the light’s effects on the water—an interest that would eventually lead to his Water Lilies series. “These landscapes of water and reflections have become an obsession,” he once said. “It’s quite beyond my powers at my age, and yet I want to succeed in expressing what I feel.”

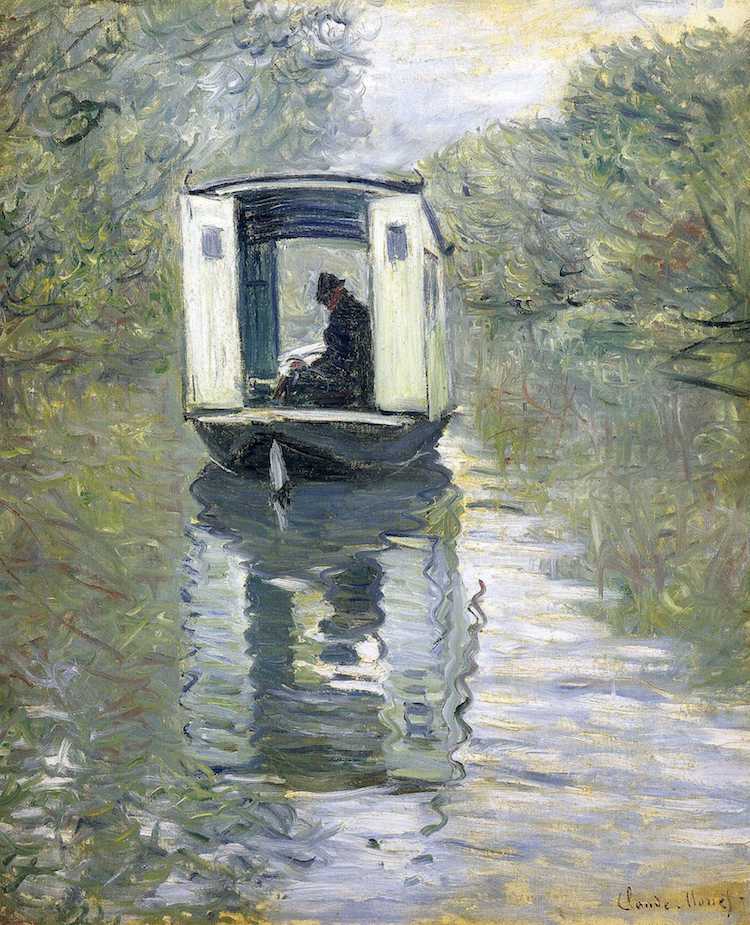

Monet would often employ his studio boat as a subject, painting it sailing down the Seine or moored at boathouses. Fellow French painter Édouard Manet also prominently featured the boat in some of his pieces, including Claude Monet in Argenteuil.

Claude Monet, ‘The Studio Boat’ (1876) (Photo: ErgSap via Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

Van Gogh’s Extra Hospital Room

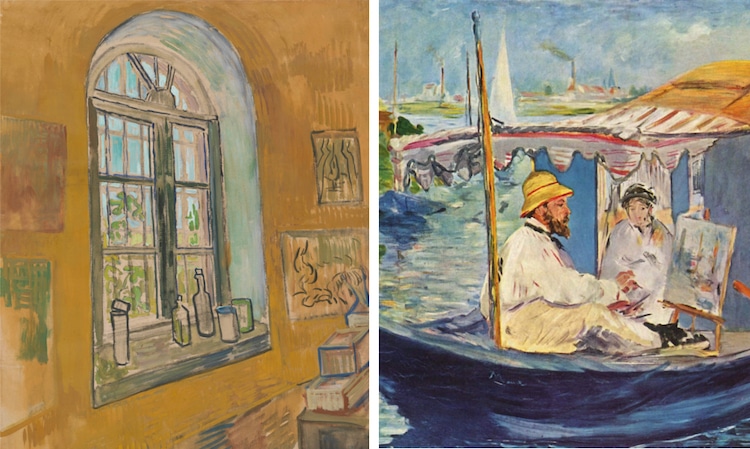

Vincent Van Gogh, ‘Window in the Studio’ (1889) (Photo: Van Gogh Museum Fair Use)

When he was just 37 years old, Post-Impressionist pioneer Vincent van Gogh died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound. At the time of his death, he was being voluntarily treated at a mental health facility in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, a commune in the south of France.

While committed, the artist continued to paint, and was even given an extra room to use as his workshop. Window in the Studio, a painting created just one year before the artist’s death, offers a glimpse of this space.

Like a typical artist’s studio, the sunny room is decorated with completed paintings and props for still lifes. What makes this set-up so unique, however, is what it overlooks. Much like the view from his bedroom window—which inspired The Starry Night—the beautiful vista from his makeshift studio is poignantly obstructed by “the iron bars of a cell.”

Matisse’s Red Room

The Red Studio shows the workshop Matisse had built for himself just outside of Paris in 1909. This piece is renowned for its eye-catching subject matter, flat perspective, and radiant red wash.

Brightly colored paintings rendered in the style of the artist are hung against the monochromatic wall, while figurative sculptures are propped up on pedestals. In the foreground, a small still life sits on a tabletop whose unrealistic angles reflect the skewed dimensions of the scene.

The painting is perhaps most celebrated for its crimson color palette, which Matisse returned to on a regular basis. Why this specific hue? “Where I got the color red—to be sure, I just don’t know,” he explained. “I find that all these things . . . only become what they are to me when I see them together with the color red.”

Related Articles:

How Museums Evolved Over Time From Private Collections to Modern Institutions

20 Art History Terms to Help You Skillfully Describe a Work of Art

5 Alternative Art Careers to Stay Creative and Move Beyond the Studio

Pop-Up Art Studio Offers Creatives an Affordable Alternative Space to Work In

Two Artists Set Sail in a Pair of Floating Art and Photography Studios