Photographer Andrius Burba captures his animal portraiture from the bottom up. That’s not just an expression—it’s the basis of his ongoing project (now brand) known as Underlook. The premise is simple, but the logistics can be complex: Burba places a cat, dog, reptile, or even horse on a piece of glass and then photographs their bellies, feet, and whatever else they care to share with us.

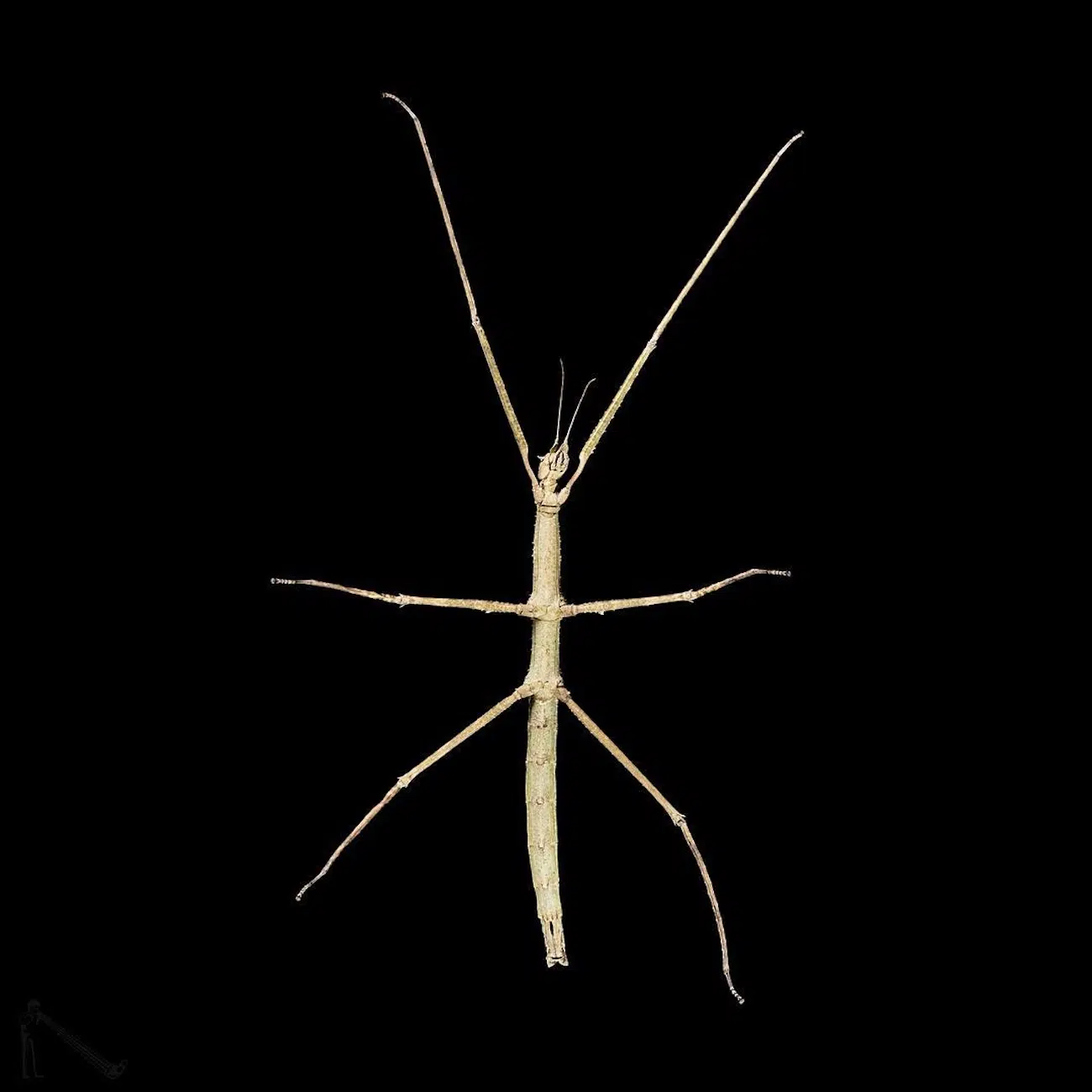

The photographic results provide a striking, clear view of fur, scales, and hooves, allowing us to understand and fully appreciate the anatomy of these creatures. “Underlook is not just about ‘cute’ or ‘funny’ images for me,” Burba tells My Modern Met, “it’s about expanding the way we see the world.”

While we think we have a good idea of what our pet looks like—after all, we live with them—the truth is we’re likely missing something because we mostly view them straight-on or from above. “When you photograph [animals] from underneath, you suddenly discover things you’ve never really noticed,” Burba explains. “How a cat folds its paws, how a dog distributes its weight, how a rabbit’s fluffy feet look softly pressed against the glass, or how big animals rest on surprisingly small contact points.”

Shot with a stark, black background, Burba’s setup affords us a valuable opportunity to study all of the parts that make the creature whole. In this way, the photographs are as educational as they are stunning.

We spoke with Burba about his journey into photography, his most memorable image, and the challenges of photographing underneath a horse. Scroll down for My Modern Met’s exclusive interview.

How did you start your photography career?

I’m currently based in Vilnius, Lithuania, and my journey into photography began when I was a teenager. At first, I was simply fascinated by cameras and the technical side of how an image is created. That curiosity slowly turned into a passion—I started experimenting with light, different styles, and realized that photography could show things we don’t normally notice in everyday life.

What first inspired the Underlook project, and what were you photographing before that?

Before Underlook, I worked as a fashion and advertising photographer. It was interesting, but over time, I started to feel that I was just repeating what many others were doing—the same kind of images, just with different clothes, locations, or lighting. I was missing a sense of

discovery.

The idea for Underlook was born the day I saw a homemade photo on the internet of a cat sitting on a glass coffee table, photographed from below. It looked funny, but it was also the first time I realized I was seeing something I had never been able to see in real life. One of the cats was sleeping with its paws folded underneath its body. I grew up with a cat who slept exactly like that, but I had never understood where those paws “disappeared.” For the first time, I could actually see them.

That moment changed everything. I understood that this was only possible because the cat was on a transparent glass surface and photographed from underneath. Naturally, a thought came to me: what else could I discover about cats if I photographed more cats from below? That idea eventually grew into the Underlook project and became my full-time work.

Your series began with pets but has branched out to all sorts of creatures. Which one have you found the most challenging to photograph?

The most challenging subjects so far have definitely been horses.

Why is that?

Photographing cats, dogs, or rabbits is unpredictable and sometimes chaotic, but technically it’s still manageable—the glass is smaller, the construction is lighter, and the risks are lower. With horses, everything becomes an engineering project.

For the Under-Horse series, the glass alone weighed around 400 kilograms (881 pounds), and it had to safely hold a horse of about 900 kilograms (1,984 pounds). We had to design a special structure, collaborate with an engineer, and even dig a 3-meter-deep pit into the ground so I could place the camera at the correct distance without using a fisheye lens. I didn’t want distortion—I wanted the horse to look real and powerful, not like a caricature.

On top of that, safety was a huge concern—for the horse, for the team, and to be honest, for myself. Even knowing that the glass could technically hold around 1,500 kilograms (3,307 pounds), when the heaviest horse (900 kilograms) stepped on it for the first time, I instinctively climbed out of the pit, just in case. So while zoo animals, reptiles, or insects each bring their own challenges, horses remain the most complex combination of engineering, logistics, and courage.

Can you describe the shoot setup for us?

The core of the setup is always the same: a custom-made glass platform with the camera placed underneath it. In reality, though, it’s much more complex than just “an animal on glass.”

The glass is the most important element. It has to be very strong, perfectly stable, and absolutely clean—because the animal is essentially standing on the “last lens” of my camera. Every little dust particle, scratch, or hair becomes visible in the final image. So during a shoot, we are constantly cleaning and checking the surface.

Lighting is another big challenge. I usually light the subject from below or from the sides, directing the light upward, but flashes and softboxes easily reflect in the glass. They can also illuminate objects under the platform that I don’t want to see in the final image. Controlling those reflections and keeping the background clean is one of the most difficult parts.

The exact setup changes depending on the animal:

- For small animals, the system is compact and relatively simple.

- For big animals like horses, it becomes a full construction site with heavy glass, support beams, pits in the ground, and a whole team around.

Generally, how long do you have to photograph an animal before it decides it’s done being a model?

It really depends on the species and personality. Sometimes I get the perfect shot in the first 30 seconds, sometimes it takes a few minutes. Cats are usually cautious and analytical—they tend to stand still, trying to understand what’s happening, which gives me a short but very focused window to shoot. Dogs are much more playful and driven by food, so with treats, I can work longer and experiment with different

poses and expressions. With zoo animals, I often only have a very brief moment—we place the animal on the glass, I take a series of shots as quickly as possible, and then we return it to its enclosure to avoid stress.

In general, I try to work fast and respect the animal’s limits. When it starts to lose interest or show signs of stress, the photoshoot is over.

Can you tell us about your favorite photo from Underlook?

My favorite and most meaningful photo is from the Under-Horse series—the brown horse with the long mane, named Epas, also known as “Rabbit.”

This image is important to me on several levels. On a professional level, it was selected among the top 80 photos out of 171,000 entries at the Sony World Photography Awards 2018. That was my biggest recognition as a photographer and a strong confirmation that this unusual perspective could stand next to more traditional photography on a global stage.

But the emotional side of this photo is even stronger. Epas was a rescue horse—he was supposed to be put down, but the stable decided to save him and give him a second chance at life. He lived many more years surrounded by people who truly cared about him. He’s a Lithuanian Heavy Draft, and his mane was officially recorded as the longest horse mane in Lithuania.

When I photographed him from underneath, it felt like capturing strength, vulnerability, history, and survival in a single frame. Technically, it was the most challenging shoot I’ve ever done. Emotionally, it became a symbol of what Underlook is about: revealing something we’ve never seen, but also telling a deeper story hidden inside one image.

Are there any animals that are on your photography wish list?

Yes, definitely—I have a kind of “dream list” that I’m slowly turning into a long-term plan. I’ve set myself a five-year goal to create three major Underlook projects with large animals:

- Under-Cows: Exploring these gentle giants of the countryside from below.

- Under-Tigers: Capturing one of the most majestic predators from a completely new angle.

- Under-Elephants: Which is probably the ultimate dream, both technically and symbolically.

Each of these animals brings unique challenges—from engineering stronger glass and building bigger constructions to collaborating with experts and making sure everything is safe for the animals.

Beyond that, I’m always curious about more zoo animals and wild species. I’d like to continue exploring creatures that we rarely see up close, and almost never from underneath—not just for the visual surprise, but also for what they can teach us about anatomy, evolution, and behavior.

Aside from being visually compelling images (and cute ones at that), what do you hope that people take away from viewing your photographs?

Underlook is not just about “cute” or “funny” images for me—it’s about expanding the way we see the world.

We think we know what animals look like, because we see them every day from the same familiar angles. But when you photograph them from underneath, you suddenly discover things you’ve never really noticed: how a cat folds its paws, how a dog distributes its weight, how a rabbit’s fluffy feet look softly pressed against the glass, or how big animals rest on surprisingly small contact points.

I hope that when people look at my photos, they feel a sense of curiosity and wonder. I want them to realize that there is always another side to everything—even to the things we think we already know very well. Sometimes viewers notice details that raise questions: for example, why is a tiger’s belly fur white while its back is camouflaged? Those small discoveries can spark bigger thoughts about nature and how it works.

Emotionally, I want my work to make people feel something—joy, surprise, nostalgia, maybe even tenderness toward their own pets. Some people laugh, some are shocked, some even cry when they see their animals from this new perspective. For me, that emotional connection is the most important outcome.

If my photos can remind people that the world is still full of unseen angles and hidden beauty, then Underlook is doing its job.