A silver teapot by Eleazar Baker, crafted in Connecticut, 1785-1800. (Photo: Yale University Art Gallery [Public domain])

America has a long and distinguished tradition of creating, selling, and owning silverware—from fancy plates in grandma’s cabinet to silver spoons in souvenir shops. Silverware refers to more than the flatware one thinks of today, though. Considered both a craft and an art, silversmiths created pieces ranging from simple spoons to enormous decorative platters. Throughout much of American history, displaying silver in one’s home was a sign of wealth and status. Silverware retained value for resale, and antique silverware can still fetch high prices. Like other decorative arts, silverware has changed with the artistic times—from the hammered drinking tankards made by the famous Paul Revere to the modern pieces for sale at Tiffany & Co.

Silver plays a critical role in American design and culture. Read on to explore the history of this precious material’s artistic use and purpose.

A silversmith’s scales and weights, 18th century. (Photo: Yale University Art Gallery [Public domain])

Colonial Silverware

Arriving with early settlers, colonial silversmiths brought their knowledge of metalwork across the Atlantic. They left the restrictive guilds of Europe behind, which had long limited who could practice the trade. In the English colonies, many silversmiths also practiced as blacksmiths, goldsmiths, jewelers, and even dentists. These careers had overlapping tools and skill sets.

A silver tea urn inlaid with ivory by Paul Revere, 1791. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [CC0 1.0])

In their workshops, the artisans heated silver, adding other metals as allowed. Traditional English silver had been standardized at 92.5 percent silver for hundreds of years. This prevented cheaper metal alloys from being passed off as real silverware. Early American silversmiths encountered some difficulty in acquiring enough silver to maintain similar standards. The English colonies did not mine silver; and without easy access to raw materials, American silversmiths often melted down coins and existing silver plate that had gone out of fashion.

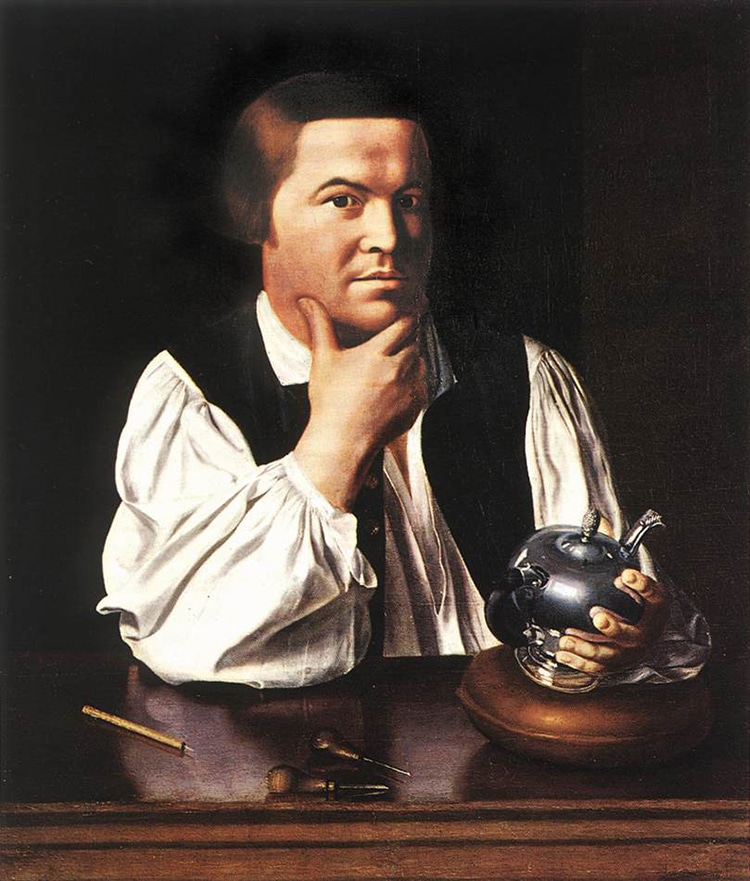

Portrait of Paul Revere by John Singleton Copley, c. 1768-1770. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

The Revolutionary period produced many prodigious silversmiths, including the famous Paul Revere. Known for his midnight ride in 1775, Revere was a silversmith, engraver, and metalworker. Talented in creating custom pieces, he also used technical innovation to produce large quantities of ready-made silver products. Revere benefited from the consumer revolution that swept England and the American colonies in the mid-18th century. A rising middle class was able—and very interested—in purchasing status symbols. A parallel rise in tea drinking offered a whole realm of possibilities—from silver spoons to teapots.

This silver teapot by Paul Revere was crafted in 1795. Its fluted design demonstrates the early stages of neoclassical influence on American silver. (Photo: Yale University Art Gallery [Public domain])

Republican Silverware

American independence from England brought standardization to American silver. The U.S. Mint set silver quantities. In 1792, the standard was set to 89.2% silver. Pieces from this date, until 1837, are known as “coin” silverware. A purer version of silver, known as sterling silver, always maintained the 92.5% of British tradition. Such regulation was important in the growing consumer market of the new Republic.

A neoclassical silver urn by Fletcher and Gardiner, 1830. Modeled after an amphora and topped with the god Neptune, this piece was commissioned as a gift honoring the completion of a canal. (Photo: Yale University Art Gallery [Public domain])

Silver styles shifted quickly. Neo-classical forms and ornamental designs were popular in the early 19th century. Although independent of Europe, Americans were still susceptible to European fashions. Following the ornate fashions of Napoleon’s new French Empire, serpents, lions, and American eagles complicated the simpler designs of early American silver.

By the 1830s, the Rococo revival encouraged strong, raised floral motifs (known as repoussé style). In this period, the famous jewelry house Tiffany & Co. was founded by Louis Comfort Tiffany. Today known for magnificent jewels, Tiffany’s early craftsmanship influenced American decorative arts with stained glass windows, silverware, and even lamps (aptly known as Tiffany lamps). Other large workshops sprung up before the American Civil War, as the tariffs of 1842 made European silver imports very expensive.

This Rococo revival Tiffany & Co. pitcher was created by William Gale and Son between 1862 and 1867, but sold through Tiffany & Co. (Photo: Yale University Art Gallery [Public domain])

In the 1830s and 40s, a new technology called electroplating was developed in England. This process allowed cheaper metals such as copper to be coated in a thin layer of silver plate. Cheaper and more durable, silver plate was often called “hotel silver” for its use in hotel dining rooms and the dining cars of trains. The “look” of having a full dining set in silver became more affordable to middle-class Americans.

The silversmith tradition also spread westward. Navajo silversmith and political leader Atsidi Sani is commonly acknowledged as having begun the strong silver-working tradition of the Navajo Nation. The Navajo previously obtained their silver goods from skilled Mexican smiths. After the Civil War, American silverware remained ornate with elaborate designs. By the end of the century, the Art Nouveau movement spread from European to American decorative arts. Art Nouveau silver reflected the organic forms seen in posters and illustrations of the period.

A Martelé silver table with Art Nouveau motifs. Martelé was a special line of extra-pure silver products produced around the turn of the century by Gorham Manufacturing Company. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

20th-Century Silver

The modern period of American silverware presents a sleeker face than its 19th-century predecessors. Modern craftsmen and designers introduced new forms to classic teapots, spoons, and candlesticks. Art Deco creations of the 1920s and the avant-garde pieces of the 1930s populate museum collections today. However, in the first half of the 20th century these pieces were often also offered directly to consumers through department stores. An interesting example, designer Paul Lobel’s austere yet graceful silver plate tea set was included in a Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibit of industrial art in 1934. Consumers could also purchase the set from Wilcox Silver Plate Company.

A modern silver tea or coffee service designed by Paul A. Lobel, and produced by Wilcox Silver Plate Company, 1934. (Photo: Yale University Art Gallery [Public domain])

Despite challenges such as the Great Depression and successive World Wars, many companies founded in the 19th century continued to produce silverware, silver plate, and other related homewares. The famed silverware producer Oneida Limited continued to create flatware in huge quantities. Founded in Connecticut in 1898, the International Silver Company harnessed the powers of golden age Hollywood to sell its silver table furnishings. Famous actresses did radio spots and appeared in print ads for the company. The company produced silver until 1983.

Mid-century modern silverware faced competition from the increasing popularity of stainless steel. Influenced by Scandinavian silver and the artistry of the Danish silversmith Georg Jensen, craftsmen continued to blur the lines between craft and art. Designers such as Robert J. King and Robert Ebendorf produced silverware alongside intricate silver jewelry.

A three piece sterling silver coffee service in the iconic “Contour” pattern, designed by Robert J. King and John Van Koert, manufactured b y Towle Manufacturing Company, 1951-1953. (Photo: Yale University Art Gallery [Public domain])

Today

Modern artists and craftsmen continue to work in silver. One can still purchase new silverware from legendary producers such as Tiffany & Co. However the allure of antique American silver—from colonial to mid-century modern—draws many collectors. Antique markets shift with the economy, and the preferences of buyers change over generations. The history of American silver offers a fountain of variety to pique diverse interests.

Related Articles:

Tracing the History of Decorative Art, a Genre Where “Form Meets Function”

Artist Turns Discarded Silverware and Scraps into Magnificent Sculptures

Artist Transforms Everyday Tableware Into Ornate Filigree Sculptures

Tiffany Lamps: The Illuminating History of the Iconic Stained Glass Fixtures