This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

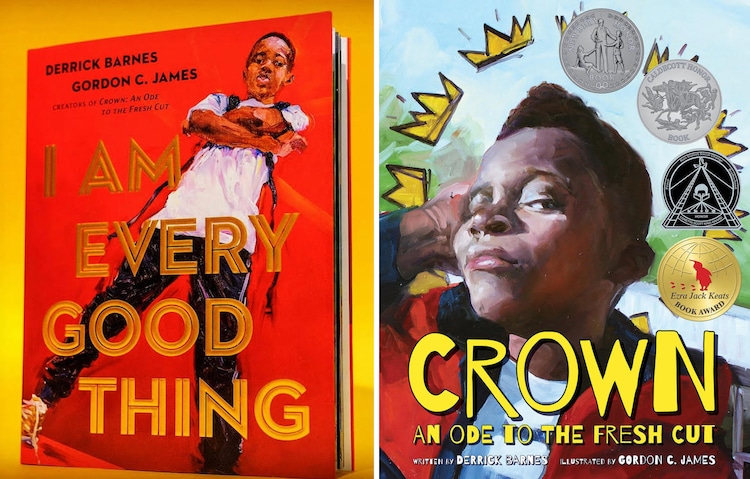

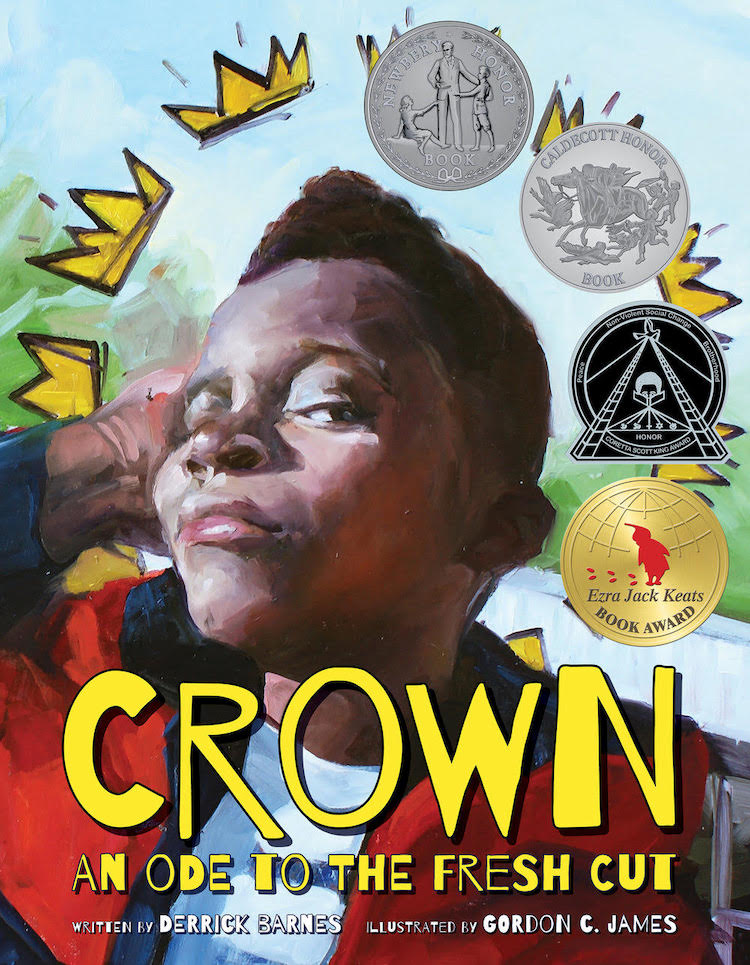

From 2010 to 2016, author Derrick Barnes could not get any of his book ideas published. The prolific writer penned 30 unpublished books during that time, and he was worried no one would ever want to publish his work again. But once his son told him to write “the Blackest children’s book he could write” Barnes authored his critically acclaimed picture book titled Crown: An Ode to the Fresh Cut. Illustrated by Gordan C. James, it tells the story of a young Black boy and the magic that happens when he gets a new haircut.

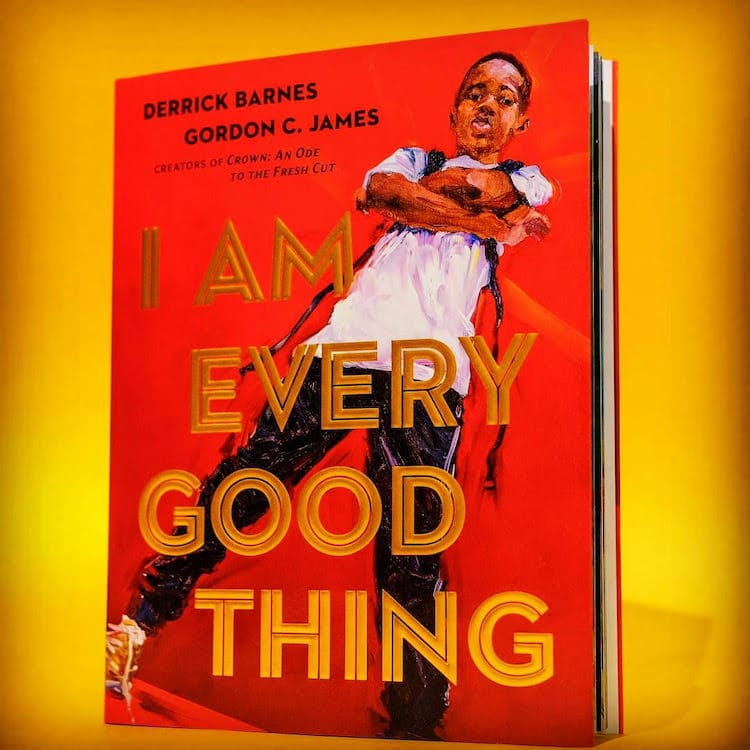

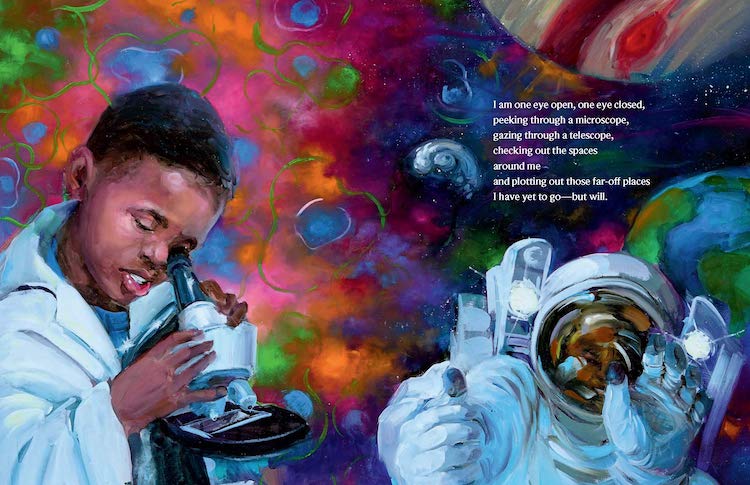

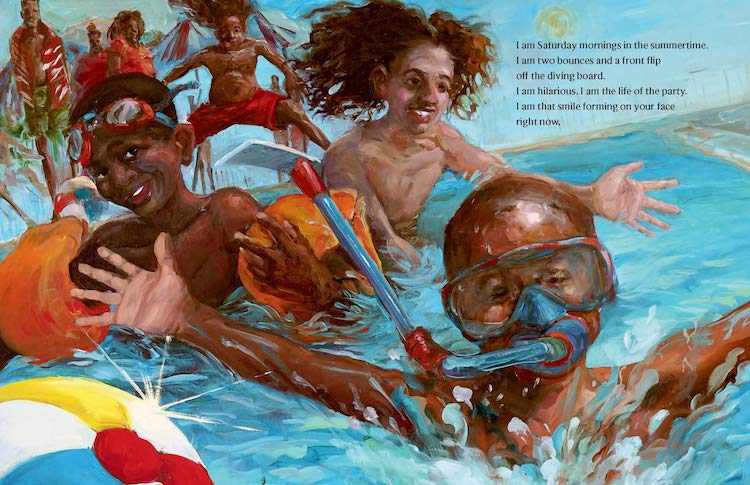

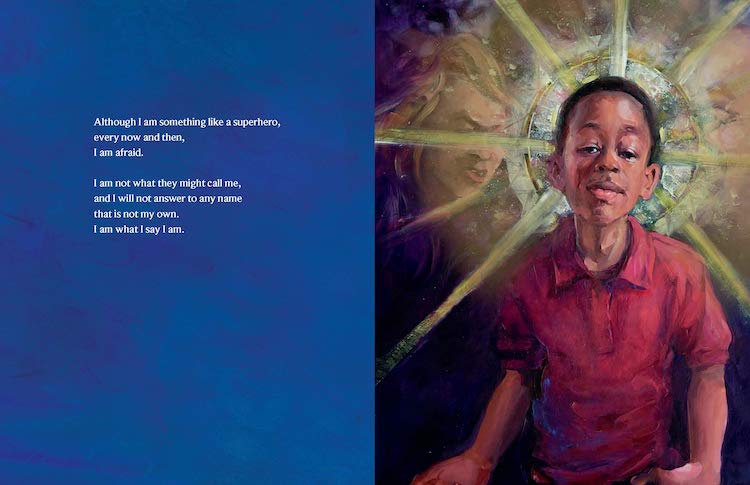

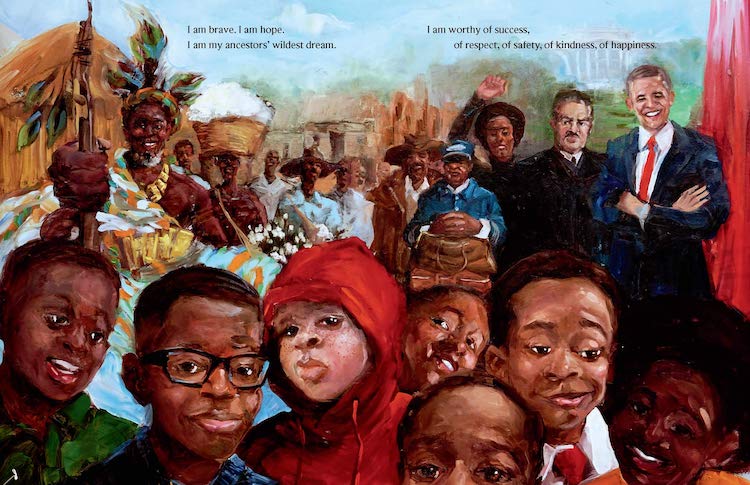

After the success of Crown, Barnes and James teamed for a new book titled I Am Every Good Thing. Like Crown, it features James’ beautiful painterly illustrations that complement Barnes’ empowering—and important—message.

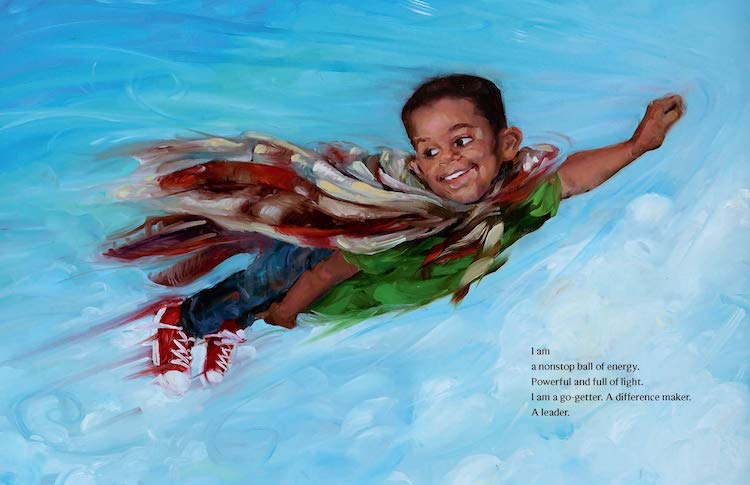

I Am Every Good Thing is narrated by a Black boy who is proud of everything that makes him who he is. He is confident and ambitious. “I am a nonstop ball of energy. Powerful and full of light,” Barnes writes in the book. “I am a go-getter. A difference maker. A leader.”

The author penned the picture book as a way to affirm Black children while showing other parents that Black children have just as much value as any other kid. “We care about and love our sons and hold them up,” Barnes tells My Modern Met, “just like every other parent does. No matter what ethnicity or race you are, we care about our sons equally.”

We had the pleasure of speaking with Barnes about his writing and the importance of language and pictures for kids. Scroll down to read our exclusive interview.

Please note that this interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Author Derrick Barnes

What is your background in writing?

I had dreams of writing, and I wanted to be a short story, novella type of writer at that point. When I came to [write greeting cards at] Hallmark [Cards], everyone there had some type of representation. They had publishers; or, if they were painters, they had art shows. It was the first time in my life that I felt like I was home. I was surrounded by tons of talented artists. I felt like I was in grad school. You know, it was just a great environment.

I met Gordon James who’s the illustrator of Crown and I Am Every Good Thing. We’ve been friends for 20 years. He helped me to get a literary agent—Regina Brooks from Serendipity Literary Agency—and she has a small boutique literary agency based in Brooklyn, New York. He gave me her information and I sent her a couple of short stories I was working on and we signed an agreement, like in 2002/2003.

The first book deals she offered to me were a dual Scholastic project. They started an African American imprint called Just Us Books, and they had a book deal for two early reader books. So there are two very short books called Stop, Drop, and Chill and the Low-Down Bad-Day Blues—those are my first books. I’ve kind of been cemented in children’s books ever since.

(continued) When you’re first trying to get into the industry, you’re just trying to get your foot in the door. I wrote my first eight books and they did okay. And, you know, I was in that whole “get my foot in the door” mode; but, between 2010 and 2016, I had nothing. It’s like nobody wants to publish my work anymore. I wrote like 30 books during that six-year span—I call that my valley period. It was tough being in my mid-to-late 30s and wondering if I’m ever going to get published again.

(continued) When you’re first trying to get into the industry, you’re just trying to get your foot in the door. I wrote my first eight books and they did okay. And, you know, I was in that whole “get my foot in the door” mode; but, between 2010 and 2016, I had nothing. It’s like nobody wants to publish my work anymore. I wrote like 30 books during that six-year span—I call that my valley period. It was tough being in my mid-to-late 30s and wondering if I’m ever going to get published again.

But then, it was 2016, and my second eldest son came into my office and he’s like, “Dad, you know, you’re already not getting published, you know what you should do? You should write the Blackest book ever, like the Blackest children’s book you can write. With du-rags and picks.” And I was like, he’s right.

And so a couple of weeks later, a friend of mine named Dante posted a picture of his son coming home from the barbershop. This is a beautiful side profile of this kid with a great haircut. So I reached out to Dante, an artist, and he thought it was a great idea. After this, I said, “I need you to sketch like 25 of these. And let me write poems about how beautiful our Black sons are, about how much we care about them.” Not so much about the haircut, but it’s about the boys. And he thought was a great idea. But he couldn’t do it because he was on deadlines for like three things. I wrote the poem and it ended up being the text for Crown. And that book changed my life.

Your books will be some of the first books that kids read and the kind they’ll remember as adults. What is it like knowing that when writing?

Your books will be some of the first books that kids read and the kind they’ll remember as adults. What is it like knowing that when writing?

My son saying to “write the Blackest book you possibly can” really sparked something in me. Every single artist, I don’t care if you make music or you’re a fashion designer, you have to keep in mind who your target audience is. I’m 45. There’s always been a dearth of positive Black imagery in children’s literature. When I was growing up, they did a lot of animal books. It was Curious George, a lot of monkeys, and almost racist epithets, or just stereotype things like having Black boys as runaway slaves or playing sports or living in the projects. We are not a monolith.

I have four boys in my house and they are four totally different personalities. I keep them in mind when I’m working on books. It was the genesis of writing I Am Every Good Thing, that we care about and love our sons and hold them up, just like every other parent does. No matter what ethnicity or race you are, we care about our sons equally.

Excerpt from “I Am Every Good Thing”

You were recently on the Drew Barrymore show and she shared clips of children and adults thanking you for the representation your book brings. Can you talk a little about that?

These books will be the first books that children of early ages—ages four through seven, eight—that they will ever see so I try to write from a universal standpoint, and write universal stories or ideas. Everyone can equate, in regards to Crown, about getting something new, a new haircut, a new pair of shoes. So it’s not specifically a Black story, but it’s very important that children of all races see other children being a protagonist, being the center of a story, being the center of a world.

I try not to beat the reader over their head with the idea that this character is Black. I don’t need to do that. It’s woven into the language. The King of Kindergarten [book] is about a kid starting school for the first time, but the character just happens to be a beautiful Black boy. And I think it’s so imperative not only for Black children to see themselves, but non-Black children to see this little Black boy in this regal role. And he may not look like me, but he has so much in common with me.

There’s a lot of children who don’t live around Black children, they don’t go to school with Black children, and the only thing they have to pull from is things in pop culture, or maybe negative stereotypes that they hear even from their own parents sometimes. But when they see my books, it gives them something else to think about, that you have to really challenge everything that you think you know about a particular group of people. So I keep that in mind.

Excerpt from “I Am Every Good Thing”

You work really closely with Gordon James. You’ve been friends for so long and your words and images go so well together. Can you talk about that relationship and your collaboration?

We respect each other’s work so much. Both of us are alpha males, especially when it comes to our work. And I am a control freak when it comes to my work. I can see the whole story laid out, visually the way I want to see things, but he likes to get the manuscript and maybe give the author something that they weren’t thinking about.

I like to give stock photography just to put the illustrator in the mindset of my vision. Gordan doesn’t want to work like that. He wants to do his own thing, which is okay with me because we both share the same mission: we both want to create books where Black and brown children are put in a beautiful, positive light. It’s just about learning how your partner works. I more so understand the way he works. I never want to step on his toes, and so I just stand back and let him do his thing. And it seems to have worked.

Excerpt from “I Am Every Good Thing”

You are empowering kids when they’re young, when they’re first getting acquainted with literature. How does that inform what you write?

Gordon says all the time that because he’s a fine artist, his work hangs in museums. We both share the same mindset that a lot of times, in regards to artwork for children, there tends to be a dumbing down. But he illustrates for children the same way he would for something that is going to be bought by a museum curator—it may be the kid’s first experience with fine art. And I feel the same way with words. We don’t need to dumb down language or visuals for children. Children are extremely intelligent and curious. And so there are a lot of words in Crown and I Am Every Good Thing outside of the age recommendations.

I’ve received emails from people who own daycare centers, I’ve received emails from language arts teachers in high school, that they’ve been able to dissect the book in the language. So, I try not to stick to any age group. It’s all about the message and the idea that you can teach new vocabulary words and ideas that really inspire children.

Excerpt from “I Am Every Good Thing”

Is there anything else you’d like people to know about you and your work?

I want to expand my voice. Obviously, I want to write more books. But I also want to do animation. I want to do film. I want to do television. I feel like I found success as soon as I started focusing on my authenticity, my voice. I feel like Crown was a hit because I’m a real stickler with language. I’m not really into using slang. But each and every ethnic group in this country has their own language and their own ways of speaking and communicating with each other. So when I wrote Crown, I put in a lot of language that I know that no matter where you come from in this country, a Black man—you live in Oakland, and you live in Brooklyn, Miami, or you live in Brixton—we all know what a fresh cut is. I can use that phrase anywhere. And we all know what fades are, and we all know what du-rags are. And I didn’t have to explain that to the editor because she was a Black woman who had Black sons. And you know, for the most part, if I had taken that to a larger house, it would have been all chopped up. They would have made me explain everything, maybe change it, but that didn’t happen.

So I said I stand committed to being authentic, not only for Black children, but we have to understand each other’s language. We’ve got to understand, appreciate each other’s nuances, appreciate each other’s differences, but still be able to see each other as human beings and respect each other’s humanity. I’m 200% committed to making sure that I keep that authentic voice.

Excerpt from “I Am Every Good Thing”

Derrick Barnes: Website | Instagram

Gordon C. James: Website | Instagram | Facebook

My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by Derrick Barnes.

Related Articles:

20+ Children’s Books That Discuss Race and Racism

Photographers Celebrate Black Beauty Through Awe-Inspiring Portraits of Children in New Book

New York Public Library Reveals 10 Most Borrowed Books of All Time